In Kayin State in southeastern Myanmar, the silhouette of an ornate city gleams along the Moei River. The town of Shwe Kokko was once a rural backwater on the Thai border, but since 2017, the construction of Yatai New City, a $15 billion project, has promised to transform its 46 square miles of farmland into a futuristic cosmopolis catering to Asia’s entrepreneurs and tourists. In a 2020 promotional video, Yatai’s Chinese-born founder, She Zhijiang, pitched the planned city as “Myanmar’s Silicon Valley,” a hub for technological innovation that might one day rival Shenzhen or Singapore.

On paper, Yatai may resemble a promising experiment for innovation and prosperity. The city, which labels itself as a “special economic zone,” is also historically beyond the direct reach of the Burmese central government. The new city’s private developer provides public utilities and maintains security. It’s also welcomed new technologies: Branding itself as a “blockchain smart city,” Yatai has embraced cryptocurrencies to facilitate everyday transactions. In 2019, it collaborated with BCB Blockchain, a Singaporean startup, to build Fincy, an app that maintains the city’s on-chain finance. By 2020, Fincy was adopted by 90% of the city’s merchants. Far away from Myanmar’s state infrastructure, the city has adopted Starlink for internet communication and solar panels for electricity.

Shwe Kokko would seem to provide fertile grounds for a startup society as envisioned by Western proponents of charter cities. In California, technologists have long reimagined cities of “exit.” Unfettered by the burdens of regulations, social ills, and vested political interests, self-governed cities could catalyze technological breakthroughs without regulatory oversight from Washington’s bureaucrats. Patri Friedman, Milton’s anarcho-capitalist grandson, for example, saw a future in cities that float on international waters. In 2008, he founded the Seasteading Institute with backing from Peter Thiel, who viewed seasteading as a means to “escape from politics in all its forms.” Balaji S. Srinivasan, who famously called for Silicon Valley’s “ultimate exit” by building “an 0pt-in society, ultimately outside the U.S., run by technology,” now envisions a world of “network states”— social networks with shared consciousness, made possible by crowdfunded territories around the world, sewn together by the internet and cryptocurrencies.

But despite its stated ambitions, Yatai didn’t become Myanmar’s Silicon Valley. Today, its largest industry is cyber scams. According to news reports, inside Yatai’s low-rise office buildings, scammers pulled victims from faraway countries into virtual romances, cultivating a trusting relationship before defrauding them with “investment advice.” Yet the scammer on the other end shouldn’t always take the full blame. Many are themselves victims of forced labor, abducted to the region from countries in Asia and Africa after responding to supposedly legitimate job postings and having little freedom to leave. In China, anecdotes of human trafficking in the region have evoked nationwide fear and anxiety as the country’s educated workers look for employment abroad in a dire domestic economy. One postdoctoral researcher, thinking he’d taken up a job in Singapore, was instead kidnapped to Myawaddy, the township in which Yatai is located, in 2022. He was only able to escape a year later after paying a ransom. In another high-profile case in January 2025, an actor responding to what he thought was an acting job in Bangkok was abducted to Myanmar, only to be rescued following the media attention triggered by the disappearance of a minor Chinese celebrity. Most aren’t as lucky: Within the high fences which enclose the city’s industrial parks, foreign workers live behind barred windows under the surveillance of armed guards. Some are tortured into obedience.

There are obviously clear differences between innovation-oriented charter city projects and rogue scam cities. Yatai’s founder, She Zhijiang, is not a tech visionary: He built a fortune running online and physical casinos in the Philippines and Cambodia. Since 2012, he’s been on the run from Chinese authorities for targeting gamblers from mainland China, where gambling is illegal. Charter cities aren’t policed by warlords, and residents and visitors come and go freely; and of course, they were not designed, like Yatai was, for scams or other criminal activities. But the stories of Yatai — and many other privately run cities in the region — should serve as a reminder of what things could look like when startup city projects go awry. As charter cities style themselves as laboratories of autonomy and exception, the “zone” as a vehicle can either catalyze economic prosperity when executed properly or facilitate global crimes when guardrails fail.

***

Building a new city outside the usual law from scratch isn’t a novel idea. In 1959, Ireland’s Shannon airport outside Limerick, which served as a fuel stop for trans-Atlantic flights, first demonstrated the economic feasibility of free-trade zones — regions where special laws and tax codes attracted foreign capital. By the 1970s, the international development community came to view special economic zones as a vessel to jumpstart economic growth. None have proved more exceptional than Shenzhen. Once a humble fishing village across the border from Hong Kong, the city was designated one of China’s first SEZs in 1980.

Carved out of China’s transitioning economy and sufficiently far away from the nation’s political center, the zone permitted local experimentation and welcomed foreign direct investment. Today Shenzhen is one of the world’s largest centers of innovation. Exempt from typical civil law and centralized government authority, the zones employ a distributed network of infrastructural power from state and non-state, market and non-market actors — an urban form that Yale architect Keller Easterling has aptly dubbed “extrastatecraft.”

China’s exponential economic growth was undoubtedly catalyzed by SEZs like Shenzhen, and the economist Paul Romer took note. In a 2009 TED talk, the future Nobel Prize laureate argued for the creation of “charter cities” in the developing world — urban areas where government authority is delegated to a strong administrator, and where rules and institutions would be largely autonomous from the host country’s laws. Hong Kong’s market capitalism, he argued, seeped into the Chinese mainland by way of Shenzhen and other coastal cities. Core to Romer’s concept is the primacy of choice: If charter cities could offer different rules and institutions, individuals could opt in by relocation. And if the city’s institutions were good enough, they would soon spread outward and bring prosperity to the rest of the country. “Could Guantánamo Bay,” Romer asked of the controversial U.S. military base, “become the next Hong Kong?”

It would’ve been a far fetch to test Romer’s idea in Cuba, but we got close enough: In poverty-ridden Honduras, where Porfirio Lobo Sosa had become president via a coup d’état in 2009, the new government took Romer’s advice to develop charter cities. In 2013, it amended its constitution to legalize its own version of the SEZ: the Zone for Employment and Economic Development, or ZEDE. Unlike Shenzhen, whose regulatory framework followed the Chinese government’s elaborate design, ZEDE permitted further flexibility by allowing charter cities to adopt their preferred, non-Honduran legal regimes and taxation systems; they could model themselves according to British law or French law, or a mixture of both. In the years that followed, several ZEDEs were built, including Ciudad Morazán and Zede Orquídea. One has been particularly high-profile: On the island of Roatán, a Delaware company operates the self-governing community of Prospéra. Tax rates are single-digit, bitcoin is legal tender, and its legal system is largely autonomous, attracting blockchain entrepreneurs and biohackers alike. The bespoke entrepreneur-friendly regimes allow for technological experimentation, without the bureaucracy — such as Food and Drug Administration rules that regulate medical trials — that retards tech progress in Western democracies. The project, however, has faced political headwinds, including from community groups that view the zone as a colonialist attack on land rights and sovereignty. The Honduran top court declared ZEDEs unconstitutional in 2024, and Prospéra is now suing the government for $11 billion, citing lost future returns. Today, the future of the project remains unclear.

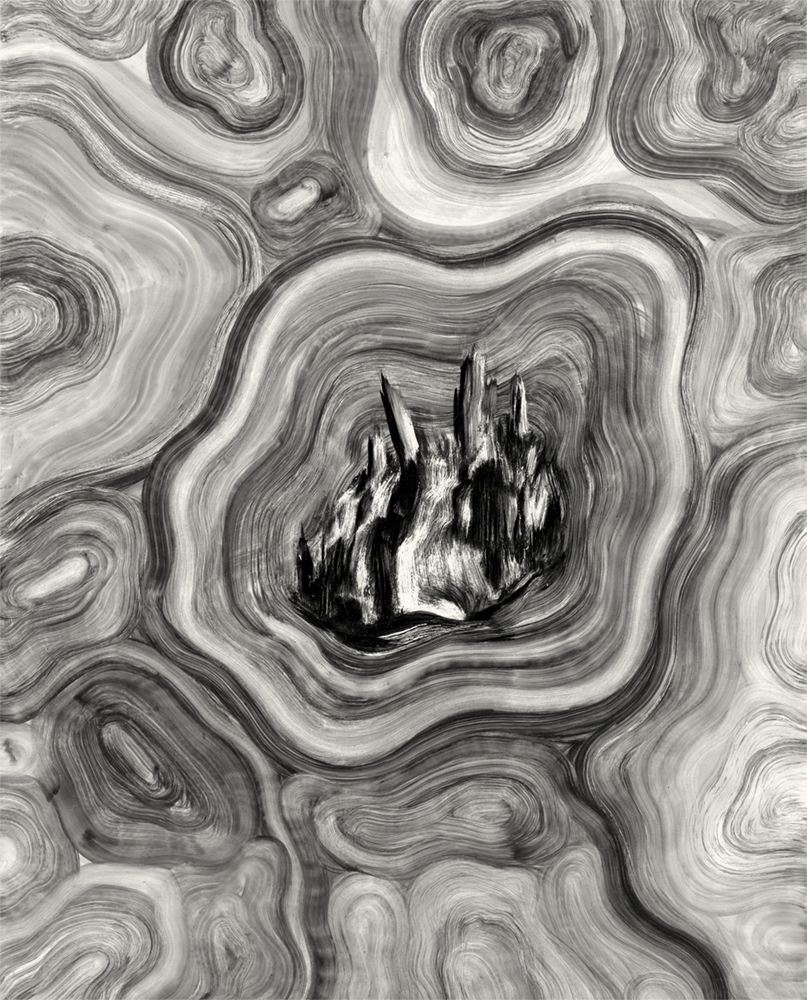

Whereas Shenzhen, Dubai, and Singapore offer successful examples of the SEZ, the visions once reserved for white papers — of truly self-governing regimes — have often found their realization in places like Shwe Kokko. The historical messiness of the region’s powers was a subject of The Art of Not Being Governed, James C. Scott’s 2009 anthropology of anarchistic societies. In southeast Asia’s unruly borderlands that Scott collectively dubs “Zomia,” many small ethnic societies were able to resist incorporation into the state-making agenda until the end of the Second World War, when communication and transportation infrastructure shortened the distance between the nation-state capitals and the anarchistic societies on the periphery. Today’s Myawaddy has metamorphosed into what Thai anthropologist Pinkaew Laungaramsri calls “Dark Zomia”— not only does the region continue to remain a site of exception to Myanmar’s state-building, but it also serves as a site immune to the reach of the Chinese state and international law enforcement. Whereas in Scott’s analysis, technologies empowered the state’s encroachment, in Dark Zomia, a web of decentralized finance, satellite internet, and Telegram channels maintains its autonomy.

Over the past decade, Beijing has been putting pressure on southeast Asian governments to crack down on the offshore casino industry; in response, kingpins like She relocated their facilities to more anarchistic locations and ventured into alternative sources of revenue. She, who had long trodden around legal gray zones, landed in Myawaddy, historically one of Myanmar’s self-ruling border regions out of the Burmese government’s reach. There he partnered with Saw Chit Thu, an infamous warlord who now leads the Karen National Army, a Buddhist ethnic insurgency, which, until recently, had aligned itself with the ruling military junta and against a rival insurgent group fighting for Karen self-determination. With casinos struggling to attract tourists during the pandemic, places like Shwe Kokko became petri dishes for highly organized internet scam operations. In 2022, Americans alone suffered an estimated loss of $2 billion from Southeast Asian cyber scams. That number rose to $3.5 billion in 2023.

Yatai isn’t the only rogue “zone.” In the Mekong region alone, clusters of scam compounds have also been identified in Cambodia, Laos, and northern Myanmar; in many cases, large crime syndicates operate across scattered geographical regions, with teams deployed in multiple scam cities. At the point between Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand, the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone operates on a 99-year lease from the Laotian government to China-born Zhao Wei, whose organization has since been sanctioned by the U.S. government for illicit activities including human, drug, and wildlife trafficking. The International Crisis Group has identified the Golden Triangle SEZ, whose grandiose casinos remain open to international tourists, as a hotbed for cyber scams. Cambodia, which has embraced SEZs through international development programs since the 1990s, created an SEZ in Sihanoukville, formerly a popular beach destination for backpackers, to attract Chinese investors. Since COVID, it too has become an epicenter for online scammers, despite central government crackdowns.

Following recent human trafficking cases and a surge in scam operations, international governments have attempted to intervene. In February, Thailand’s government tried to cut off electricity and internet access across the border. BCB Blockchain, the Singaporean start-up which built Yatai’s cryptocurrency, left Yatai in 2020 following allegations of financial crimes, but other cryptocurrency infrastructure outside the international regulatory regimes has continued to service rampant criminal activities. She is currently in Thai custody awaiting extradition to China for operating illegal casinos and facilitating telecom fraud. In May, the U.S. government imposed sanctions on Saw Chit Thu, the warlord who leads the KNA, and his associates for facilitating cyber scams, human trafficking, and smuggling. But the industry remains difficult to crack down on: Scam compounds in Myawaddy have gone off the grid. Some have moved to other parts of southeast Asia. Starlink has kept scammers online, according to a WIRED investigation.

Can startup cities go rogue? SEZs coordinated by strong states (e.g., Shenzhen), charter cities run by foreign capitalists (e.g., Prospéra), and Dark Zomia in weak states (e.g., Yatai) have produced varying outcomes. Praxis, another U.S. charter city startup which shares investors with Prospéra, has vowed to build “acceleration zones” in the Mediterranean where “new technologies will not be preemptively regulated.” Yet the difference between criminal enclaves and innovation cities isn’t solely one of intent or ideology but also the political and institutional environments that permit the state of exception to occur — and, therefore, the zones to exist. Just as Shenzhen became a symbol of economic modernity, Yatai is now a cautionary tale of what happens when extrastatecraft becomes criminal infrastructure. Juridical autonomy, technological experimentation, and regulatory flexibility naturally render the zones fertile grounds for abuse. In the complete absence of regulation and oversight, SEZs can become sanctuaries not only for innovation but for impunity as well.