Whenever life gets you down, look up the Hockey Stick of Long Run Growth.

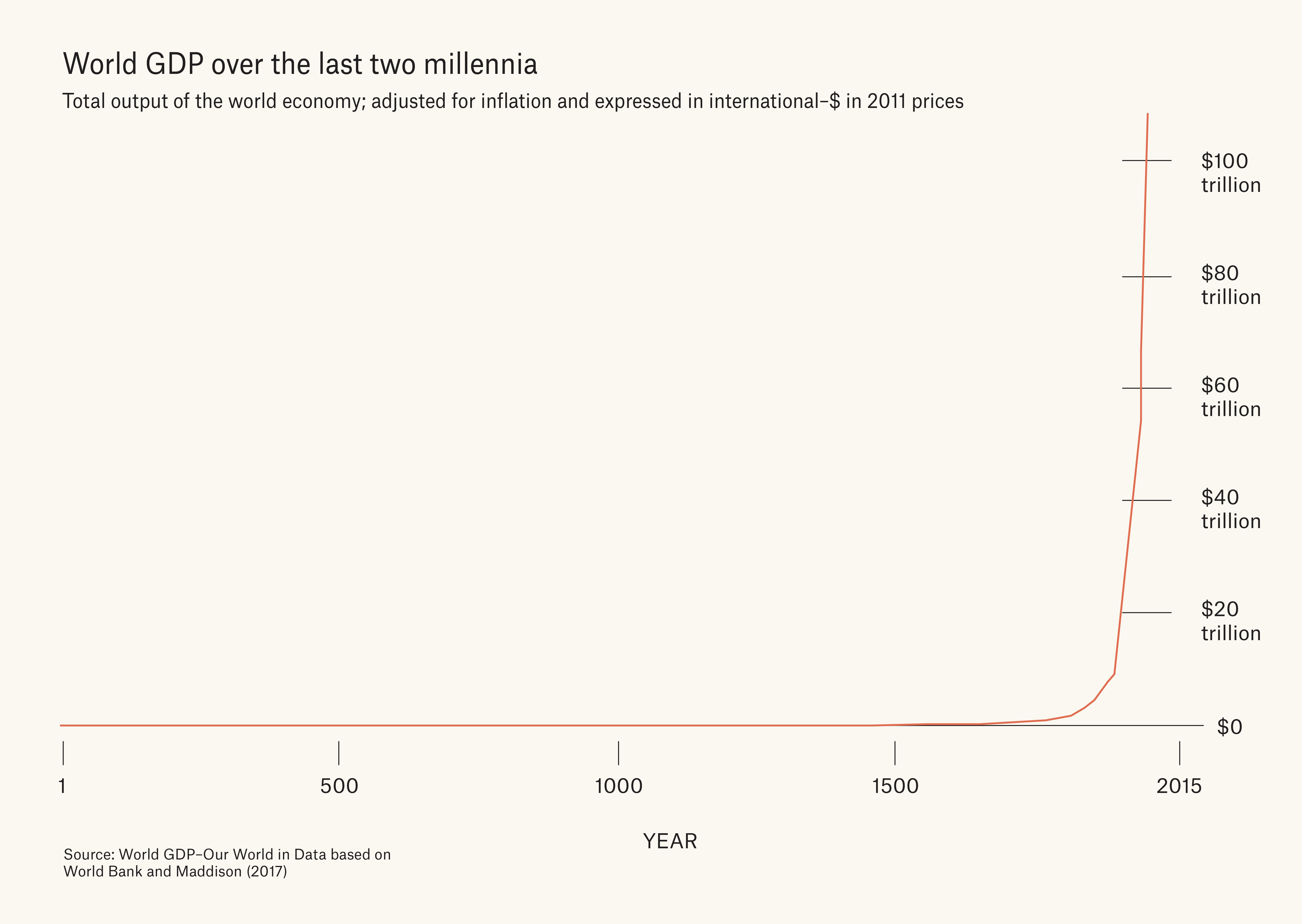

You’ve surely seen it before — those measurements of GDP which stretch back to antiquity and, post-1800, show an explosion of economic growth.

Everyone loves the hockey stick graph of long-run economic growth. For some, it's the basis of an entire worldview. Unfortunately, the numbers don’t add up.

Whenever life gets you down, look up the Hockey Stick of Long Run Growth.

You’ve surely seen it before — those measurements of GDP which stretch back to antiquity and, post-1800, show an explosion of economic growth.

For a certain type of nerd — the kind who knows their spinning jennies from their water frames, weeps silently at museum steam engines, and includes, perhaps, this writer — seeing that line rocket upwards triggers a certain frisson. Within that slender line is condensed so much of humanity’s material progress, its scientific and technological achievement, its grasping towards the possibility of lives that are a little less nasty, brutish, and short.

The Hockey Stick of Long Run Growth has acquired a life of its own as a sort of emblem of belief in the potential for human progress. It has been printed in textbooks, sewed onto hats and, in all likelihood, has somewhere been tattooed on human flesh.

All very well and good, but for one nagging question.

Which government bureau was collecting GDP statistics in the 1st century?

Most long-run GDP data can be traced back to a single source: the Maddison Project, named for the late British economist Angus Maddison, who built an august academic career on the art of historical GDP estimation.

A self-proclaimed chiffrephile — one who loves numbers — Maddison brought quantification to places where historians previously feared to tread. Thanks to his efforts, historical GDP estimates were brought back to 1820, then to 1000, then in one giant leap, back to the birth of Jesus Christ. After Maddison passed away in 2010, his intellectual heirs at the University of Groningen picked up the work, updating his estimates with the latest findings from economic history research.

To get to the heart of the matter, in its latest 2023 release, the Maddison Project estimates that in 1 CE, Roman Italy had a GDP per capita of $1,407 in 2011 purchasing power parity dollars. Elsewhere in the Roman Empire, Greece had a GDP per capita of $1,275, roughly 10% less than Italy; Egypt, a breadbasket of the Mediterranean world, had a GDP per capita of $1,116, roughly 25% less.

By expressing everything in the common units of 2011 purchasing power parity dollars, the Maddison dataset enables mind-boggling jumps across both space and time. For instance, Romans in Italy transported to 2022 would be counted among the poorest people in the world — somewhat poorer than the average Madagascan (GDP per capita $1,367 in 2011 PPP dollars), but somewhat richer than the average Malawian ($1,190). A modern Roman, at $36,224 per capita, is around 26 times richer than her ancestors in 1 CE.

The Maddison estimates’ appeal likely lies in how they immediately help us grasp history in quantitative terms. On the one hand, they give us a sense of the scale of material transformation since the Industrial Revolution: denizens of one of the richest premodern societies on the planet lived in material poverty we commonly associate with the developing world. On the other hand — a still grimmer thought — people in present-day developing countries are living in material conditions comparable to those 2,000 years ago.

But to return the original question — who was collecting survey data in the reign of Augustus Caesar? Where do these GDP numbers actually come from?

We can immediately dispel the notion that there was anything close to a Roman Bureau of Statistics. The Romans were pioneers in census-taking, road-laying, and aqueduct-building, but any notion of systematically estimating national wealth or income would have to wait until at least the 17th century.

All of the Maddison Project estimates for 1 CE come exclusively from a 2009 paper by Walter Scheidel and Steven J. Friesen, who make a valiant latter-day effort to piece together Roman GDP from the fragments of surviving evidence. From the middle of the first to the middle of the second centuries, Scheidel and Friesen have precisely one price of wheat for all of Roman Egypt. For unskilled workers’ wages (measured in terms of wheat), they have three sources: Diocletian’s price edict of 301 CE, papyri from the mid-first to second centuries, and papyri from the mid-third century.

Triangulating three sets of estimates from these scattered observations, Scheidel and Friesen arrive at a final total GDP estimate of 50 million tons of wheat at the Empire’s population peak around the mid-second century CE, with a per-capita consumption of 680 kg of wheat or equivalent grains. 1 If we say that subsistence is 390 kg of wheat, and assume that subsistence is worth $400 in 1990 PPP dollars, this translates to $700 in 1990 PPP dollars, giving us the $1,116 in 2011 PPP dollars for 1 CE. (1 CE is still a hundred-odd years off from Scheidel and Friesen’s chosen data point in the mid-second century, but no matter.)

Compare this process, for a moment, to the modern production of gross domestic product. The concept of GDP was born in Depression-era America and Britain, and came of age in a time of mobilization for total war. Today, American GDP is compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (with 500 employees and a $100 million annual budget), which builds on the work of over 4,000 employees and $1.6 billion at the Census Bureau, which itself builds on the surveys of the hundreds of thousands of temporary workers who canvas the country every decade — a hiring surge that needs to be statistically smoothed out of national employment figures, or, more fancifully, an act of economic observation so massive it perceptibly alters the economy around it.

Needless to say, four or five surviving data points for every few centuries is hardly in the same category.

To be fair, the scholars whose work underlies the Maddison Project are making the best educated guesses from fragmentary, often frustratingly elusive, evidence. But GDP estimation is hard even when backed by the resources of a rich industrial government. Pre-modern GDP estimation is closer to that of an under-resourced state like Zambia, where, in 2010, the national accounts were assembled by a single person. (Indeed, modern developing states often have to grapple with similar problems of legibility, since most farming is for household subsistence and never observed in a market.)

The problems with the Maddison Project’s pre-modern GDP estimates are not isolated to ancient Rome. In a scathing 2009 review article, Gregory Clark, another prominent economic historian, described Maddison’s pre-1820 figures as fictions, “as real as the relics peddled around Europe in the Middle Ages.”

Clark’s specific critique addressed the medieval GDP estimates in Maddison’s 2007 data, which he deemed implausibly low; surviving evidence on the daily wages of unskilled English laborers from the 1440s suggest they were earning several multiples of subsistence levels. But his attitude is representative of a large number of economic historians, who look askance at the Maddison Project’s leaps of quantitative conjecture to come up with estimates of GDP.

Defenders of the Maddison Project argue that historical quantification forces scholars to get precise about their assumptions, and sets the ground for a reasoned debate. And indeed, the rounds of argument and counterargument around Maddison’s initial dataset have proven quite productive — after Clark’s salvo at Maddison’s implausibly low estimates for Britain, those figures have been replaced in 2015 by new estimates from Stephen Broadberry and coauthors. Most of what remains is still conjecture, but perhaps better conjecture than before.

And simply — wouldn’t you want to know how rich the Romans were? Shouldn’t the economic always be quantifiable?

Much of the economic history debate is focused, quite rightly, on scrutinizing the ingredients that go into estimating ancient GDP. But it’s worth asking how much the exercise of long-run comparison is even conceptually coherent.

The Maddison Project provides GDP figures in terms of 2011 purchasing power parity dollars. To put this in plain English: when it states that Roman Italy in 1 CE had a GDP per capita of $1,407 in 2011 PPP dollars, it is saying that the average Roman produced enough to buy $1,407 worth of everyday goods in 2011 America.

We should dwell a bit longer on what this precisely means. “Purchasing power parity” is one of those unfortunate phrases that the eye readily glazes over, like “Wet Floor” or “Terms and Conditions.” I think many laypeople (and not a few economists) assume that it’s something that the experts have figured out. As usual, the truth is messier.

The purchasing power parity exchange rate is the imaginary rate that would make a good cost the same across countries. For instance, if in 2025, a Taco Bell Cheesy Gordita Crunch costs $5 in the US and 20 yuan in China, then the 2025 Cheesy Gordita Crunch PPP exchange rate would be 4 yuan per dollar. This logic can be extended to a whole basket of everyday goods to create an overall PPP for the cost of living. Today, the World Bank’s International Comparisons Program meticulously collates price baskets across over 100 countries to assemble these PPPs, which help inform critical development metrics like the famous dollar-a-day poverty line.

The trouble begins when one realizes there is really no such thing as a global basket of common goods. In Japan, breakfast traditionally includes fish and some pickles; in landlocked Mongolia, perhaps a cup of mare’s milk tea; in the United States of America, a soup of sugared corn in chilled cow’s milk. Reasonable substitutions are often possible — wheat can stand in for rice, rambutans for kiwis — and if we’re willing to look beyond exact matches, perhaps “fruit” or “grains” can stand in as broadly comparable categories. But often the central assumption of PPP estimation, that the price of an identical good can be compared across countries, is not satisfied.

These problems become particularly stark when comparing poor and rich countries. How do we reconcile the spending patterns of a rural Malawian family, where, in 2011, fewer than 10% of people had access to electricity, with an American household where electricity powers everything from fridges to TVs? We can find close-enough substitutes; we can adopt broad, sweeping categories (like “Recreation” or “Energy”); we can try to statistically adjust goods for their relative quality (more on this in a moment); or we can simply admit defeat. In a 2010 article exploring PPP estimation, the economists Angus Deaton and Alan Heston sounded a note of exasperation. “Aspects of the exercise are close to being impossible in theory,” they write, “and are therefore not amenable to data improvement.” (Deaton won the Nobel Prize in 2015, in large part for his contributions to the measurement of consumption in developing contexts.)

But we’ve strayed a bit from the original question. What does it even mean to say that a 1st-century Roman could afford to buy $1,407 worth of goods in 2011 America, when most of the goods the typical American buys were not yet invented? At a minimum, how does the Maddison Project adjust for changing prices when tackling historical GDP?

The short answer is that it doesn’t. The key assumption to getting the Maddison calculations to work, which I’ll quote from the paper underlying the latest release, is that the “underlying price structure of every nation’s economy remains fixed over time.”

“Assuming that prices remain fixed over time” is the kind of academic sleight-of-hand that grinds economic historians’ teeth while leaving most readers perplexed. But this benign-seeming assumption can break most of our economic intuitions.

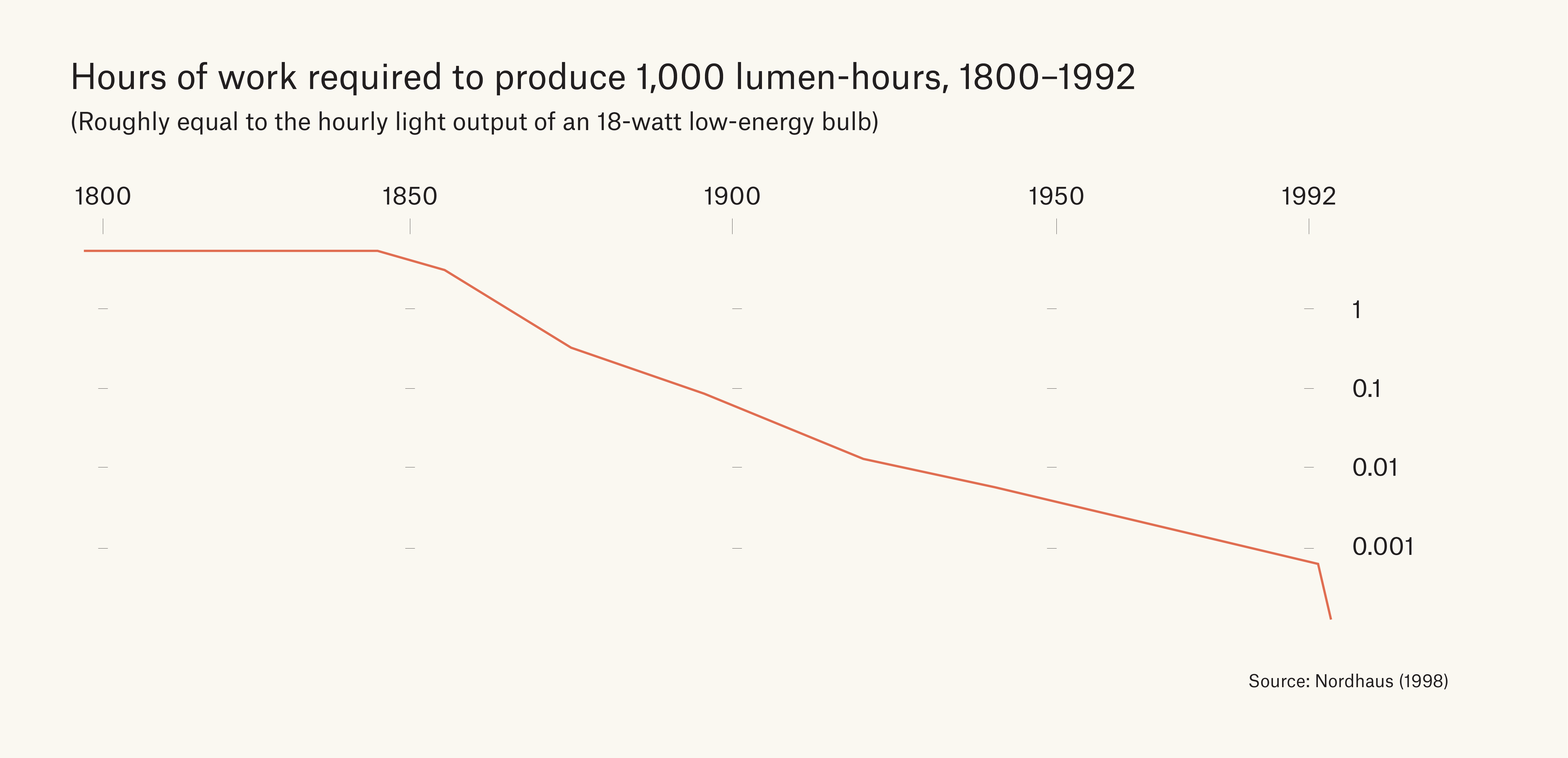

Take light, a technology which over the last few hundred years has seen enormous technological change. Helpfully, the “quality” of a light source is straightforward to quantify: we can compare the amount of illumination it generates over a fixed span of time (measured in lumen-hours) to its energy cost (which can be measured in British thermal units, or Btu).

According to calculations by the economist William Nordhaus, a tallow candle from 1800 could produce around 22 lumen-hours per 1,000 Btu. This was a modest 25% improvement on the technology the Romans had on hand: an antique Roman terra-cotta lamp that Nordhaus tested (provenance: Spirits, Inc. of Minneapolis) could burn 60 ml of sesame oil for 17 hours, for 17.5 lumen-hours per 1,000 Btu. But a first-generation fluorescent bulb from 1992 could produce 20,011 lumen-hours per 1,000 Btu — roughly a thousandfold improvement in efficiency over the past two hundred years.

Moreover, looking solely at the technological change actually understates the extent of the economic improvement. To gauge the real price of lighting, Nordhaus compared lighting efficiency to the cost of labor. In 1800, it took 5.4 hours of labor for the average worker to afford 1,000 lumen-hours — roughly the 18-watt bulb emits for an hour. By 1890, with the widespread adoption of electricity, this price had dropped to 0.133 hours. In 1992, when Nordhaus, this had dropped to 0.00012 hours — a 45,000-fold decrease in the real cost of lighting.

Nordhaus’s calculations on the falling cost of light have become a celebrated example of the transformative power of technological progress. But the radical implications for GDP growth are often underemphasized.

Most conventional estimates of GDP largely ignore Nordhaus-style calculations, implicitly assuming that the quality of lighting is fixed. 2 Under this assumption, the Maddison data estimates that real US GDP per capita has risen 1,363% between 1800 and 1992. Real wages show a similar 13-fold increase over that period.

But what happens if we take the radical, alternative view that technology results in quality improvements over time? Nordhaus calculates a “high-bias” scenario, where a larger share of goods show quality improvements proportionate to light; and a “low-bias” scenario, where more goods have “run-of-the-mill” properties. In his low-bias scenario, from 1800 to 1992, real wages grew not by 1,363%, but by 4,000%; in the high-bias scenario, real wages grew by 19,000% — which would imply a US GDP per capita of $483,550 in 2011 PPP dollars.

These kinds of calculations leave us with two unpalatable alternatives. Either we must take contemporary incomes as given and project backwards incomes that are infinitesimally small — implying that populations lived far below modern subsistence-level incomes of around $400 PPP dollars a year — or we have to take low incomes in the distant past as given, and attribute to ourselves far greater wealth than we previously imagined.

Or, perhaps, there is a third possibility: recognizing the limitations of a statistical tool that has been stretched well past its original design.

Consider this the confession of a reformed chiffrephile. There’s an undeniable temptation to compare the productivity of Caesar’s Rome to modern Japan. But if we reject easy quantifications, we can begin to embrace a richer understanding of the past.

The absence of a handy Roman GDP statistic forces us to confront the meager economic data points we have: some literary references and a few papyri scattered across the centuries. It reminds us not only that Rome was a nation without a Bureau of Economic Analysis, but a polity that could hardly be called a nation at all, with an economic structure which bears little resemblance to modern industrial societies — one dominated by vast latifundia worked by slaves (should these be considered households, and excluded from GDP?), consuming a basket of goods which were either wildly out of reach in labor-prices or so meager it falls below subsistence. It’s unsurprising, then, that a 20th century tool to measure the economic power of industrialized nation states starts to fray when stretched to the scale of centuries. GDP is set up to measure continuity when the process of long-run growth is really one of radical change.

And this is not just a sterile academic debate. The problems of long-run GDP apply equally to projections of the far future. If history is any guide, new technologies, traveling at the speed of light, can rapidly outpace statistical agencies’ ability to measure them. Yes, this will likely lead GDP to underestimate the true rate of growth, but to merely tweak the quantification is to largely miss the point. New inventions bring new preferences and unthought-of tastes, which render the notion of a fixed basket of consumer goods nonsensical; they can bring forth new organizational forms, which redraw the boundary between the household and the market; and, at their most radical, they can usher in dramatic institutional change, revising the Domestic in which Gross Product is made.

We should expect transformative technological change to break the metrics we use to measure it — because it already has.

By highlighting text and “starring” your selection, you can create a personal marker to a passage.

What you save is stored only on your specific browser locally, and is never sent to the server. Other visitors will not see your highlights, and you will not see your previously saved highlights when visiting the site through a different browser.

To add a highlight: after selecting a passage, click the star  . It will add a quick-access bookmark.

. It will add a quick-access bookmark.

To remove a highlight: after hovering over a previously saved highlight, click the cross  . It will remove the bookmark.

. It will remove the bookmark.

To remove all saved highlights throughout the site, you can click here to completely clear your cache. All selections have been cleared.