“Despain? Yeah, it’s a French name, but my family is from England for about as far back as it matters. Probably we came from some part of France near Spain before that.”

It’s funny how incurious we can be about the names and traditions we carry. I grew up a Mormon from a long line of Mormons, who see family history as a religious duty. Because of that, it was my birthright both to have a stunningly complete family tree stretching back at least 15 or 16 generations down most lines and to mostly ignore it, secure in the understanding that it existed should I ever care.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints repeatedly calls its adherents’ hearts and minds to the past. It orchestrates “pioneer treks,” where young members pull handcarts for a few days in a reenactment of the church’s westward journey. It produces stirring films and pageants that present a glowing vision of the early church. Its leaders warn against becoming “a weak link in the chain of your family's generations.” I grew up in a living tradition, one that made itself felt and demanded strict adherence.

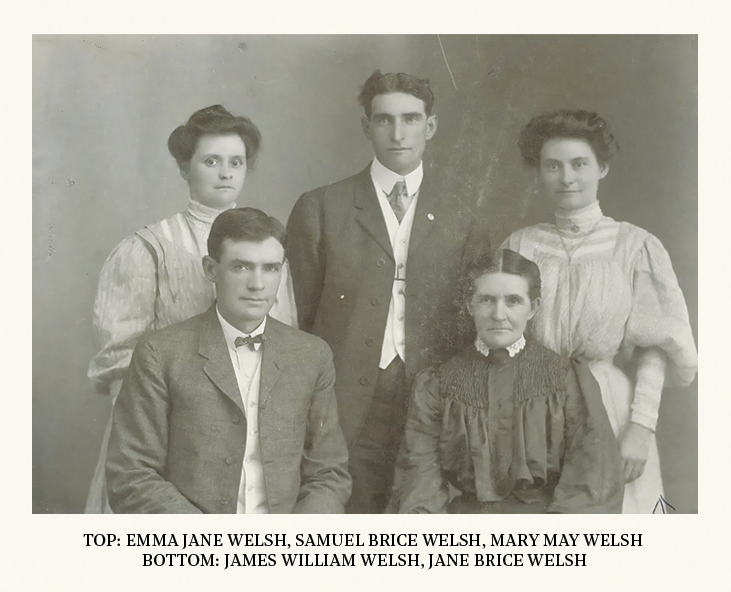

In most tellings, the tradition started at one specific point: the pioneer crossing. All of history before the founding of Mormonism was a footnote, a prelude. My family loved to tell the story of my third great-grandmother Jane Brice, who dictated and passed down the saga of how she came from England to Utah in the disastrous Martin Handcart Company at 10 years of age. The company left too late in the season and got caught in winter. One-quarter of its members died, including Jane’s mother. Jane herself developed frostbite, which left a hole in her ankle. In her telling, when what remained of the party finally arrived in Utah, her father saw it and said, “This is nothing but a godforsaken desert! I’m going back to England with the first company that travels east.”

He returned to England without Jane, who hid sobbing in a woodpile when the wagon train came so that he couldn’t find her and take her back. She stayed, she explained, "Because Mother said this is where we should be, and she died trying to get here. I know this is where I should stay!”

Powerful story for a Mormon kid to tell as his local church community pulled handcarts through the mountains in commemoration.

We also loved telling the story of how our third great-grandfather William Jordan Flake founded the incongruously named Snowflake, Arizona, along with our fifth great-granduncle Erastus Snow. William Jordan Flake’s father, James, is most memorable today for having sent Green Flake, an early Black Mormon, to Utah as his slave. He would ultimately gift Green Flake to Brigham Young. We didn’t tell that one as often.

My family knew our history was romanticized, but we didn’t press too hard. “Not one of the Martin handcart company ever apostatized or left the Church,” members would often quip, and my siblings and I would slyly wink at each other and think of Jane’s father. But Jane was a model for us.

Tradition has a way of haunting me now that I’ve left. Something about the present moment. I listen, occasionally, to the Quebecois traditionalist song “Dégénérations,” which romanticizes the sentiment:

Your great-great-grandfather cleared a little piece of land / Your great-grandfather helped to plow the field by hand

And your grandfather took it, made it grow and made it thrive / Then your father sold it off and took a steady nine-to-five

As for you, young man, in the city all alone / In a one-bedroom loft winter chills you to the bone

When you dream at night you feel the shovel in your hand / As you walk the fields of that little piece of land

It traces a path common to many of my generation: ancestors on farms with large families, gradually proceeding to a portrayal of isolated and atomized city living — a hint of progress, a hint of loss. The song captures a sentiment embodied in the term “Retvrn:” the sentiment that perhaps our ancestors were onto something, that we have lost something essential in modernity.

What would it mean for me to Retvrn to tradition? For a number of my friends and contemporaries, it has meant converting to Catholicism or Orthodox Christianity as adults. Perhaps the most famous such convert is JD Vance. “I really liked,” as Vance once put it, “that the Catholic church was just really old.”

Catholicism represents tradition. Perhaps that’s why a surprising number of people in my circles — young men, very online, alienated by perceived “woke” cultural and institutional dominance — have flocked to it. In a time of passionate moralism and sweeping cultural change, many have concluded that perhaps the best they can do is submit to an institution old enough and strong enough to provide a firm cultural and moral alternative to social justice progressivism.

But Catholicism is not my tradition, nor is it the tradition of my ancestors, even in the pre-Mormonism footnote within my family story. I was amused to find that not a single person in my family tree, so far as I could identify, was Catholic — not for centuries back, as far as the 1500s. As soon as my family could step away from Catholicism, they did.

Take the story of where my surname actually comes from. My first ancestor to come to America was Samuel Despaigne, my eighth great-grandfather. Samuel was born in 1692 into a tiny French Huguenot refugee community in Canterbury, England. The Huguenots were French Protestants who left the country in several waves in the face of persecution from the Catholic French government. They brought the word “refugee” to the English language, along with a tradition of weaving.

By the time Samuel was born, multiple generations of his family had been born as refugees in Canterbury, each marrying strictly within their own Huguenot community. He reached adulthood in a time of crisis for that community: the East India Company had opened trade with India, Persia, and China. By 1710, when Samuel was 18, the weaving industry in Canterbury had fallen 50% from its peak. Virtually his entire family died in the 1720s: his mother, his brother, his four children, his wife. Having lost his industry, his family, and his community by his mid-30s, he emigrated to America alone in 1728, where he built a new life and a new family for himself.

***

I bought a Huguenot cross after learning Samuel’s story, following the grand American tradition of eagerly embracing a newly discovered ancestral culture. The scale of Samuel’s loss makes my own stakes seem small. I cannot help but feel his story is worth remembering in more detail than “French name, but definitely from Britain.”

Yet his story is not like the living tradition that Mormonism was for me, an all-consuming force that shaped every part of my childhood, my family, and my culture. It’s more like it scratches the same itch as reading about Catholicism or the Roman Empire does for many young online people — especially those who feel they lack living in a rich tradition. Culture changes, technology changes, and humans remain the same, with the crises of each new generation echoing those of the past.

How did that living tradition start in my family? In the 1800s, Mormonism spread like wildfire to my ancestors. All but a handful of lines joined the Mormon pioneer movement and migrated to Utah. What made the LDS Church so compelling? One element, which they articulated at the time, was a desire to restore something that had been lost.

Many of my ancestors who joined the faith were descended from Puritans who had come to America two centuries before Mormonism’s founding to build their vision of a city on a hill. The Puritans were successful, in a sense. Their colonies thrived. Their culture and values were foundational to the American project. But in another sense, well, their church crumbled and faded into history. The burned-over district in early 1800s New York — so-called because so many fires of religious revivalism had swept through it that people felt there was no spiritual fuel left to burn — had drifted far from the Puritan vision. At the time Joseph Smith began to preach, around 1828, the people living there still carried the same spiritual baggage as the Puritans: predestination anxieties, millennial expectations, and the conviction that America held special divine purpose. But now they found themselves caught between countless revivals and new denominations. Lacking, in other words, tradition.

Joseph Smith preached a message of restoring what had been lost. He weaved every bit of the world around him — and everyone who cared to join him — into a grand divine narrative. A hill near his home was no longer just a hill, but the burial place of ancient sacred records. America was not just a country, but the Chosen Land, its inhabitants descended from ancient Jews. Missouri was not just a place for his followers to migrate to, but the original site of the Garden of Eden. Smith’s story posed a question to all he met: Would you choose to be heir to a divine legacy, living a life imbued at every step with rich spiritual meaning, playing an essential role in a mission to redeem the world with the promise of living forever with your family — or would you rather just farm? In that environment, how could Joseph Smith not have won converts?

***

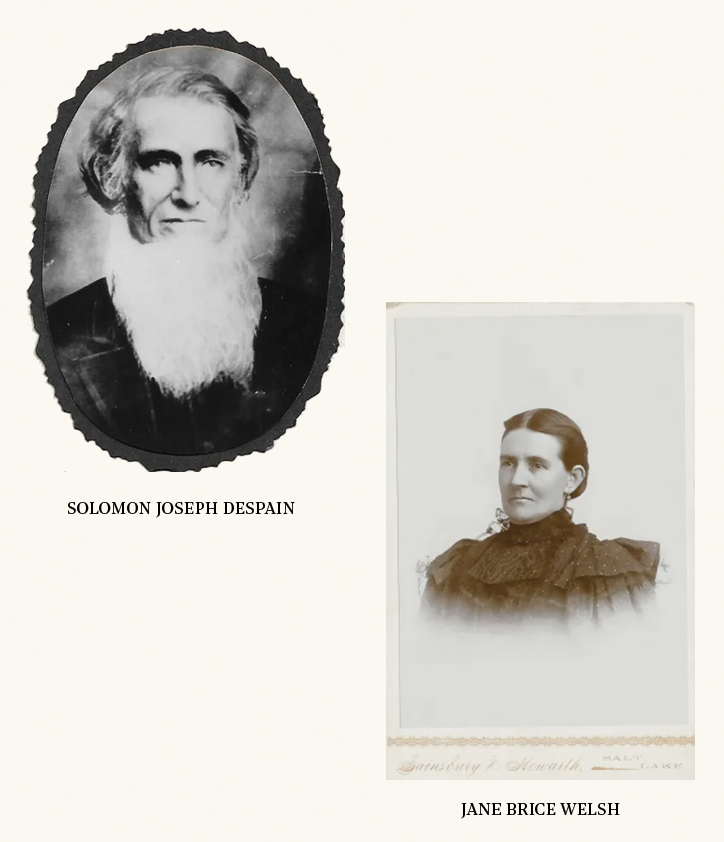

Samuel’s great-great-grandson Solomon Joseph Despain was the first of my paternal line to join Mormonism. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had all moved to different states, pushing the American frontier further outward. His recent ancestors were Huguenots, Dutch and German Reformed, Anglicans, and more, leaving him a scattered patchwork of traditions common to Americans of his era. Within that patchwork, he and his wife Ruth converted first to the “Campbellites,” an 1840s sect committed to restoring primitive Christianity, then to Mormonism, joining the trek West in 1861. By joining Mormonism, he was not abandoning his tradition. He came from many traditions and no tradition, with the clearest common thread among his ancestors being a commitment to going somewhere new to practice a strange and demanding new faith. In that light, his trek to Utah to build a Mormon city on a hill was the most natural thing he could have done.

(The story of Solomon’s first wife, and my fourth great-grandmother, Ruth Amelia Newell, gives a more somber look at the past: “Father got tired of an ailing wife and became faultfinding which made Mother very miserable and unhappy, and they were never as happy again. Some time before 1858 Mother took a young girl, Susan Dean, in to live with us. She came to Utah with us and some years after Father married her as his second wife. Mother's trials were many. She was so unhappy when her first girl was born that she cried three days and nights because she was afraid she had brought a girl into the world to suffer as she had done.”)

***

I am in the uncommon position of knowing with crystal clarity just what the traditions of my ancestors were. For as long as Mormonism has been a religion, my ancestors were Mormon — six to eight generations back, all the way back to Joseph Smith’s grandparents. Before that, they were Puritans, German Palatines, Huguenots. Again and again, my ancestors found their traditions collapsing against modernity. Again and again, they made the bitter decision to sweep everything up, leave their homelands and their old faiths, and build something new.

Why? The clearest answer is that my people left their traditions when those traditions failed them. Even when they spoke of Retvrning, they wound up building things that were radically new. Joseph Smith, claiming to be restoring ancient Christianity, instead built a quintessentially novel American religion. My ancestors left everything to chase that utopian vision into the desert.

That tradition echoes in my name: a French name gesturing toward Spain, carried by religious refugees first to England, then to America, then to Utah. My family has a rich, half-millennium-old tradition of never retvrning. Instead, they built new cities on new hills. They combined strict conviction with an equal willingness to step away from traditions that failed to meet the needs of the times. To do anything less — to crawl back to older forms after many generations of passionate and hard-fought escape from them — would be a betrayal of that legacy.

***

When I was 22 years old, I stepped away from the only faith and culture my family had known for generations. My departure was less dramatic than Samuel leaving his profession, family, and culture to sail to America. It was less dramatic than Jane hiking for months across the plains before curling up in a woodpile so that she could stay.

For close to a decade before that point, I had studied my faith seriously — almost desperately. First, it was as a cocky teenager diving into apologetics, confident I could be both skeptic and Mormon. Then, as the questions became thornier and the answers less satisfying, it was as a young devout. I tested my religion on its own terms. I followed its commandments wholeheartedly. I prayed, I read the scriptures, I spent months on my knees each night begging my God for a hint of light. I traveled to Australia for two years of missionary service to invite people into a faith I felt was good — even when I could not say I knew it was true. Finally, in the two years between my mission and the day I left, it was as a shell, as I attempted to persuade myself every contradiction and senseless moment was part of a grand divine plan. Until I found my mind being torn in two.

My ancestors sailed across an ocean and pulled handcarts across the plains. I created the online handle “TracingWoodgrains” and challenged ex-Mormons on Reddit to convince me of what I had tried to keep myself from knowing for years. I experienced leaving Mormonism not as relief, but as the feeling that the world was wrong and could never be put right again.

How, then, should I Retvrn? Like my family before me, I see no path backward, no option but to face the present directly. The world is not yet burnt over. The city on a hill remains to be built.