A couple of years ago, my wife and I were driving from our home in rural Illinois to St. Louis. The drive begins with corn fields, but after an hour gives way to the outer ring suburbs commonplace in any major metropolitan area. As we passed an area known mostly for the shopping centers, strip malls, and chain restaurants endemic to suburban sprawl, my wife pointed out a fairly nondescript warehouse-looking building off the highway. It had been freshly painted, and the parking lot had a new coating of asphalt.

The only thing that made this building stand out was a sign with a generic-looking logo — maybe a tree, maybe hands in prayer — and a single word, “Ascend.” “Is it a church?” my wife asked. We googled it. It wasn’t, as we expected, an upstart, non-denominational church. It was a marijuana dispensary, one of a number of stores cropping up on the Illinois side of the Mississippi as a result of the state’s legalization of recreational weed. We laughed about that for the rest of the drive into the city, sure that we couldn’t be the only ones unable to tell the difference between a new church or a dispensary.

People talk a lot about the decline of religion in the United States, and there are a lot of data points that back up that claim. In 1972, the General Social Survey reported that about 90% of American adults identified as Christians. Just 5% said that they had no religious affiliation. Fifty years later, the share who were Christian had dropped to 62%, and the “nones” had risen to nearly 3 in 10. The share of the population who reported attending a house of worship nearly every week was 41% in 1972 but had declined to 23% by 2022. The “headline statistics” certainly point in the direction of growing secularization.

That’s also true if one digs through the minutiae of denominational record keeping. The largest evangelical denomination in the United States — the Southern Baptist Convention — went on an incredible run of growth during the post World War II period. For decades, the SBC added a million people to their membership rolls every four or five years. That culminated in the Convention reporting a membership of 16.2 million people in 2006 — an increase of about 10 million from sixty years prior. But since that high-water mark, the Convention has reported consistent losses which have appeared to accelerate in the past few years. In 2022 alone the church shed 457,000 members. By 2024, the total number of Southern Baptists dropped below 13 million, the same size as in 1975.

And it’s not just the conservative congregations. Mainline denominations have recorded huge losses too. The Disciples of Christ lost nearly three quarters of their members between 1987 and 2022. In the same period, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America dropped 45%, and the Presbyterian Church USA dipped by 62%. The United Methodists, who had 10 million members in the late 1960s, just endured one of the largest denominational schisms in American history — losing a quarter of their churches and members in an 18-month window. Today, they number fewer than five million.

However, parts of American religion are seeing tremendous growth. As my wife and I noticed, there are hundreds of churches popping up in strip malls and converted warehouses across the United States. They often have vaguely spiritual names: the Journey, the Village, or the aforementioned Ascend. If there’s any bright spot in Christianity, it’s the rapid rise of non-denominational evangelical churches, which seem to have emerged out of nowhere to supplant the Presbyterians, Lutherans, Baptists, and Methodists in how the average American thinks about the religious landscape of the United States.

This is a recent phenomenon. When Roger Finke and Rodney Stark published their magnum opus, The Churching of America, 1776-2005: Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy, it was the culmination of thousands of hours of archival work on American religion dating back to the Colonial era. The book exhaustively detailed the patterns and trend lines of faith communities in the United States since its founding. Yet the word “non-denominational” doesn’t appear once in its over 300 pages, and for good reason: When they were writing the first edition of the book, non-denominational churches were only a marginal movement in Protestantism. In the last few decades, that’s completely changed.

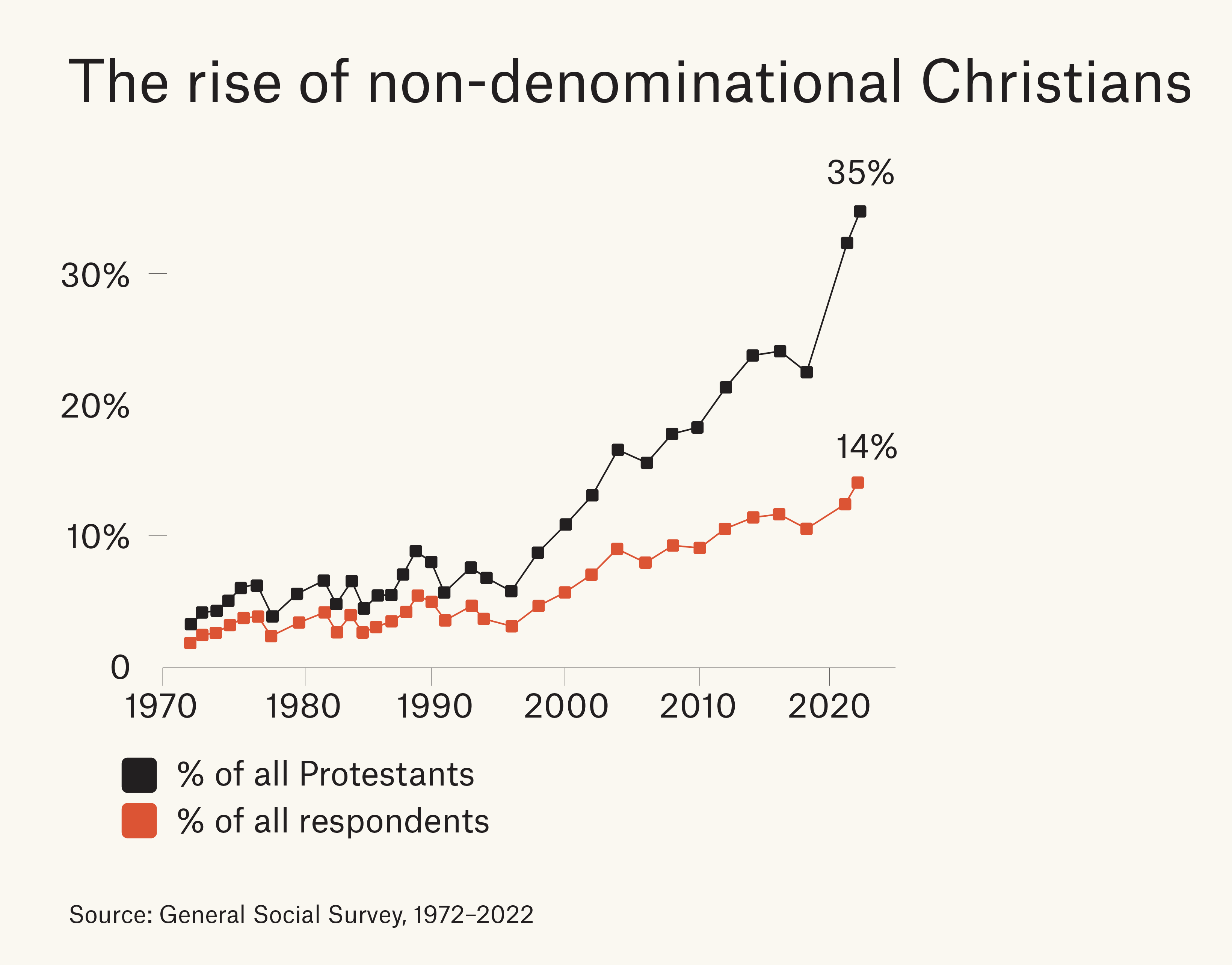

When the GSS began asking about religious affiliation in 1972, there were more non-religious Americans than there were non-denominational Christians. In that very first sample, just 34 souls were non-denoms — one would forgive Finke and Stark for overlooking what was a little more than a rounding error. In fact, the share of all Americans who identified as non-denominational didn’t reach 10% until 1998. But growth has been rapid in recent years. The share of Americans who are non-denominational has doubled since 2005. Even more striking is how Protestantism as a whole is being consumed by the non-denominational juggernaut. Just 1 in 20 Protestant Christians said that they were non-denominational in the 1970s. Today, it’s one in three.

It’s nearly impossible to calculate the raw number of non-denoms, given the diffused and disorganized nature of the movement. A researcher can’t just call up the record keeper for tens of thousands of these churches and ask for membership statistics. That approach was much easier when Protestantism was arranged around denominations that were well organized and invested in detailing statistical analysis. So our best estimate available comes from the 2020 Religion Census, which counted over 21 million non-denominational Christians in the United States. However, there’s good reason to believe that is an undercount, given that 14% of all Americans say that they are non-denominational. If that figure were extrapolated to the entire U.S. population, the number of non-denominationals could be as high as 45 million. For comparison, the Catholic Church in the United States counts 62 million adherents.

Why and how did American Protestantism shift so quickly from a world of strict hierarchies, robust denominational bureaucracies, and an emphasis on credentialism to its antithesis?

One answer may lie in a force already shaping every aspect of society, politics, and culture — a deep distrust of institutions. America’s deepening distrust of institutions appears in the data over and over again. Today, when asked about how much confidence they have in banks, Congress, medicine, labor unions, or even religion, very few people express a “great deal.”

In 1975, the share of Americans who held “hardly any” trust in banks was 11%. Now, it’s 23%. Distrust in the United States Congress and in the Supreme Court has also doubled, from 26% to 53% and from 8% to 16%. Across the 13 institutions the GSS has asked about for decades, Americans only feel more confident in one: the United States military. The media has taken the biggest hit of all. In 1975, just under 1 in 5 Americans (19%) said that they had hardly any trust in the press. Today, it’s more than 1 in 2 — a majority position. It’s the only institution where distrust is clearly above 50%.

Why did this happen? It’s hard to know for certain. We live in a very different world than 1975, and social science gets more difficult as more variables change over time. Long-term polling data points to one specific inflection point when institutional trust began to erode — Watergate. Up until that point, the media took a fairly collegial — one might even say protective — approach to covering the White House. Reporters considered it out of bounds to publish on FDR’s polio or JFK’s extramarital activities. But when Richard Nixon’s administration orchestrated a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, a more adversarial style of journalism emerged — not just because scandal sold newspapers, but because the media had begun to reconsider its role in holding power to account. As sociologist Michael Schudson has argued, public trust in the press may have been too high before Watergate, and the decline in trust that followed was in part a healthy correction.

The rise of 24-hour cable news networks in the 1980s and 1990s further altered newsroom economics. The machine demanded content — and figures like Bill Clinton and Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker provided more than enough fodder to keep viewers tuned in.

The erosion of institutional trust is one of the most important macro-level changes in American society of the last several decades, and it’s incredibly difficult to point to a single causal factor.

But any casual glance at an algorithmically generated social media feed makes it clear that this new technology has helped accelerate a significant rebalancing of social power. For centuries, the thought-industry of the West has been dominated by gatekeepers. College professors decided which students would earn a seat in the most prestigious graduate programs. Newspaper editors made the call on what type of essays were worth the ink. Book publishers decided which young authors with some ideas about the future of the country were worth the publishing risk. And American Christianity was made in the image of those in authority who decided who would fill the pulpits of the most iconic Protestant churches throughout the United States. Importantly, religious gatekeepers were heavily influenced by the decisions made by the seminary professors and book publishers who were deciding what voices to broadcast to the millions of congregants sitting in the pews of tens of thousands of churches across the country.

There is no longer a gate. With the rise of YouTube, podcasting, and Twitter, any charismatic thinker can develop an audience that could easily be counted in the millions. No one is required to list their scholastic bonafides before opening a stream. No one is perusing the CV of the person in the TikTok they’ve just been served. They want to be entertained — and possibly educated — in the bite-sized moment they have waiting for the next train. This technology seems especially adept at transforming the world of American religion. Spend any amount of time online, and it quickly becomes apparent that there’s a new breed of religious entrepreneurs giving people what they want, how they want it — and eroding centuries-old religious institutions in the process.

The seeds of this revolution can be traced back to a few compelling church leaders who broke with evangelical tradition. The most prominent was a preacher named Bill Hybels who, in 1974, dreaming of starting a new church, decided to find out why people in the Chicago suburbs weren’t members of one. Common answers were that churches asked far too often for money, made them feel guilty, and seemed irrelevant to their daily lives. People wanted an atmosphere that was more casual, welcoming, and friendly. Hybels gave them exactly this in Willow Creek Community Church. Founded in 1975, Willow Creek consciously departed from prevailing patterns of evangelical life. Many of its innovations — rock bands, stage lighting, services crafted for the unchurched with deliberate avoidance of insider jargon — are prominent in non-denominational churches today. It was, by any objective metric, a smashing success. Within six years, it had gone from a congregation of 125 to 15,000. In 2018, the average weekly attendance was nearly 26,000, making it the fifth largest church in the United States. Crucially, it has never been attached to any formal denomination.

Hybels’ approach became known as the “seeker sensitive” model of church growth. It took a few years for the word to spread about this new approach to church planting, but within twenty years of Willow’s success, thousands of young pastors, in every region of the country, adopted the model with designs on repeating the explosive growth that they were reading about in evangelical books and magazines. Few of these pastors sought out advanced seminary degrees, or any of the other aspects of credentialing that were traditional for clergy in Episcopal, Methodist, or Presbyterian churches. The only approval they needed, so these young men said, came from God himself. Protestant Christianity started to look a lot like Silicon Valley, with a motivated entrepreneur with little more than an idea and a garage. Just like venture capitalists are drawn to the possibility of getting in the ground floor of a startup company, lots of eager Christians want to say that they were the founding members of what could become a megachurch in a few years.

One of the most famous and more recent examples of these church planters was Mark Driscoll, who started Mars Hill Church in Seattle in 1996. The typical path of a successful pastor is to first attend seminary, followed by pastoring a small church or joining the staff of a larger congregation as a youth pastor. Then, by their late twenties or early thirties, those years of toiling in relative obscurity pay off when they found their own church. Driscoll did none of those things. He was 25 years old when he founded Mars Hill. Though he had become an evangelical Christian at 19 years old, his only relevant educational experience was a bachelor’s degree in communications. In fact, Driscoll had never been a member of any church at all before he founded Mars Hill. He famously stated that the first church he ever became a member of was Mars Hill. It was only later, after several years at the helm of Mars Hill, that Driscoll would earn a graduate degree in theology.

If he had been born two or three decades earlier, a man like Mark Driscoll would have never been given the opportunity to preach a Sunday sermon — let alone lead a church of 15,000 members. And he held his lack of experience with pride. The “outsider” status of Mars Hill — and Driscoll himself — was part of its DNA. Last year, he went as far as to denounce his own degree, publishing a video titled “Seminary is a Waste of Money” — a slap in the face to the thousands of Driscoll supporters who spent years of their lives earning degrees that he claimed were not worth the time or effort.

The reason that this message was so effective was because it catered to a specific type of individual — one receptive to religion and spirituality but allergic to the institutional nature of the American church. This comes through clearly in the data. In the 1980s, 30% of non-denoms said that they had hardly any trust in organized religion. Among Christians who were part of a denomination, just 17% had hardly any trust. When Mars Hill began in the mid-1990s, the trust gap was just beginning to narrow, which made some sense — as the concept of non-denominationalism was becoming mainstream,it seems likely that members of places like Mars Hill would have seen the church as “organized religion.”

That gap in trust between non-denominational and denominational Christians persisted through the 1990s. Then something interesting happened. The share of non-denominationals with low levels of trust began to decline. It dropped from about 30% between the 1970s and the 1990s to just 20% in the last three decades. The share of denominational Christians with low trust didn’t shift much at all. The end result of that is the “trust gap” that made non-denominationals distinct has disappeared. Why? A possible explanation is that non-denominationals could only ride the outsider wave so long. After 2000, they began to be perceived as part of the establishment. Their disorganized nature became organized out of necessity as non-denominationalism continued to make gains in American religious life. Non-denominationals became the organized religion they previously distrusted.

But that didn’t mean that Mars Hill didn’t continue to emphasize their novelty and rebelliousness. One of the reasons for Driscoll’s rise to fame, and the sustained growth of his church, was his aggressive approach toward digital media at a time when virality was still a novel concept. Mars Hill hired staff who could elevate the church in the national conversation. They made Driscoll into the face of new evangelicalism, and he made it easy for them. According to former staff members, Driscoll would intentionally try to create viral moments during his weekend sermons. For instance, in 2009 he scolded the men in the audience by screaming, “How dare you?” at them multiple times in a message about gender roles. That sound bite was so controversial and polarizing that it was even shared on Christian radio stations.

This led to him being asked to go on national news programs like Nightline to debate theological issues, such as the existence of Satan. Mars Hill had taken a page out of the books of the televangelists of the 1970s and 1980s — they didn’t need the communications apparatus of a denomination like the Southern Baptist Convention or the United Methodist Church to build the church’s profile; the democratization of social media made it possible without any institutional support. The end result is a much more fragmented evangelical landscape that is almost impossible to explain to outsiders and even more difficult for news outlets to cover.

But religion is not the only area in which social media has shifted the locus of power — it has also come to the world of American politics. When one looks back at the types of politicians who managed to successfully navigate the politics of their own party and the arduous journey through the primary process, the winner tended to be someone from the establishment. Mitt Romney, John Kerry, and Joe Biden had each spent decades in politics, building connections, and refining a public profile palatable to a wide swath of the voting public. When Barack Obama ran for president, his campaign was lauded for its use of social media to get the word out — especially to young voters. But while his message was certainly about hope and change, it certainly wasn’t focused on “burning it all down.” Obama, at his core, was — like the vast majority of politicians who came before him — an institutionalist. His plan for bringing about a better America was through reforming the institutions that already existed.

Donald Trump used his growing platform on Twitter to roll metaphorical grenades into the discourse. It seems like a lifetime ago, but Trump made his first significant foray into American politics in 2011 by commenting incessantly that he believed Barack Obama was not a citizen of the United States. While John McCain had intentionally steered his supporters away from conspiratorial thinking during the 2008 campaign, Trump did the opposite. He poured fuel on the fire. While Trump had a long history of media appearances, his foray into politics gave producers a new reason to book him on their programs, and they did so consistently during Obama’s second term.

When Trump announced his candidacy as a Republican, the GOP hierarchy went into a frenzy. They wanted to throw their weight behind an establishment candidate like Jeb Bush or Ted Cruz. Yet despite the RNC’s best efforts, the Republican base couldn’t get enough of the real estate magnate from New York City. Trump also received the endorsements of evangelical outsiders like Paula White — whose gender, prior divorce, and prosperity-gospel preaching were far out of step with Southern Baptists. The GOP establishment secretly convened a meeting to devise a strategy to stymie Trump’s ascendance. Obviously, it failed. Donald Trump won the White House on two separate occasions, less on an outsider stance and more on an explicitly anti-institutional platform. His constant rantings about the “fake news media” and the “deep state” could be disseminated through social media channels that had no gatekeepers and very little censorship. These messages were consumed voraciously by followers who also believed they were being held down by invisible forces that they could easily chalk up to institutions and societal structures that did nothing to elevate their station in life.

There’s a narrative theme in the Gospel of Luke, often described by biblical scholars as “the Great Reversal.” In the Kingdom of God, the last shall be first, and the first shall be last. The Jesus of Luke’s Gospel is always looking at the edges of the crowd for the sick, the lonely, and the ostracized. Jesus says things like, “But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation” (6:24). He tells a story about a rich man and a beggar named Lazarus who lived outside the rich man’s house. Both characters die, but only Lazarus is carried to Heaven, while the rich man is made to suffer in Hades for all eternity. The purpose of this story is clear — the world to come is one that reverses the current state of affairs.

It seems that we have already seen the Great Reversal happen in 21st century America, but it does not look anything like the Kingdom of God described by Jesus in the Gospel of Luke. Yes, the gatekeepers have been taken off their lofty perches, and the advent of smartphones and social media has given anyone the power to broadcast their message to millions of people at a moment’s notice. Institutional structures have crumbled, and outside voices have been elevated.

But has this change left us for the better? The two non-denominational pastors described above are instructive. While Bill Hybels managed to grow Willow Creek to be one of the largest churches in the United States, it has been brought low in the last few years. Attendance dropped from over 25,000 in 2018 to less than 10,000 in 2024. A primary cause was the uncovering of Hybels’ sexual relationships with a number of women in the church. As for Mark Driscoll, he was forced to resign as the pastor of Mars Hill in 2014 for abusing his pastoral authority. Less than three months later the church was dissolved.

American evangelicalism has never been as fractured as it is right now. For decades, the movement was led, unofficially, by Billy Graham. Often referred to as “the evangelical pope,” his crusades were watched by millions of American evangelicals who were already sure of their salvation. Now, there is no figure in the movement who can coalesce similar widespread support. Pastors like the aforementioned Paula White are not welcome among the Southern Baptist establishment. Joel Osteen, who may be the most famous preacher in the United States, never appears at events or panels with other prominent voices in evangelicalism. The end result are relatively small evangelical fiefdoms across the United States, where a pastor may have a flock of 15,000 or 20,000 and a few hundred thousand followers on social media but is largely unknown by the average American. The cohesiveness that drove the Religious Right in the 1980s and 1990s has all but disappeared.

But what may be the true downside of this Great Reversal is that accountability has given way to cults of personality. A clear-eyed view of the Trump presidency is of a man who believes that he is elected to carry out his agenda and anyone who stands in his way should be removed. But accountability can often become an issue in these non-denominational churches, too. When the local Methodist church has an allegation of sexual abuse or financial misconduct, church officials have someone to call for help. What happens when this occurs at The Journey or The Village? The true risk of the bottom-up realignment of American society is that power is often concentrated in a single individual.

When the Framers of the United States Constitution were debating the power-sharing structure of the new American government at the Second Constitutional Convention, they were all deeply familiar with the writing of French nobleman Baron de Montesquieu. His most important work, The Spirit of the Laws, had been published less than forty years before they met in Philadelphia. In it, Montesquieu compellingly argues for institutional accountability. “In order to have liberty,” he wrote, “it is requisite the government be so constituted as one man need not be afraid of another.” Convincing the average American that they should actively work toward the destruction of every institution around them may have had the opposite effect — now, many of us are fearful in a way that we’ve never been before because we aren’t sure that any of our leaders will ever face real consequences for their actions.