Science in the United States is in turmoil. The Trump administration has threatened universities with impossible demands, canceled billions in grants and terminated contracts wholesale, proposed a new budget with dramatic cuts to science funding, and fired thousands of government employees at funding agencies.

What happens now?

It seems dire at the moment, but much remains to be determined. A great deal depends on two questions: whether Congress is able to put its foot down via future appropriations and legislation, and whether courts backstop Congress by upholding the Impoundment Control Act, a 1974 law enacted in the aftermath of the Nixon presidency that places tight restrictions on when and how a presidential administration can refuse to spend allocated money.

In the immediate future, the most damaging aspect of the current chaos may not be the cancellation of grants per se, but the effects on personnel. In theory, grantmaking could be re-upped as early as this fall. However, even if funding is fully restored, it’s possible there won’t be sufficient government employees to even begin to handle the workload. Onerous immigration policies could mean that labs can’t even implement the work they had proposed.

It might take a few years to get back on course. By that point, scientific progress may have been stifled and derailed. Does that matter? Yes. When progress is at hand, even a few years of chaos and stalling can put our society on a different and lower course than the alternative. All the more reason to think carefully about the long-term effects of short-term policies.

A background belief

I’ll begin with a foundational assumption: Federal science funding is a good thing. There is no other funder willing to spend billions on basic science with no immediate market applications (at least not since we dismantled nationwide monopolies like AT&T and its funding of Bell Labs). The economic literature consistently shows strong economic returns from federal funding to R&D.

Andrew Fieldhouse and Karel Mertens of the Dallas Fed estimated that “government-funded R&D accounts for one-fifth of business-sector [productivity] growth since WWII,” and that even before the second Trump administration, we were substantially underfunding science. Their 2025 paper adds to this evidence, estimating that “if the R&D increases authorized under the CHIPS and Science Act were fully appropriated,” there would be a “boost in U.S. productivity within a few years, reaching gains of 0.2–0.4% after seven years or more,” raising “output by over $40 billion in a single year.”

In April, another set of economists estimated that “a 25 percent cut to public R&D spending would reduce GDP by an amount comparable to the decline in GDP during the Great Recession.” If annual public R&D spending were cut in half, they estimate it would make the average American approximately $10,000 poorer than would be predicted from historical GDP trends. And in May, economists Ed Glaeser and David Cutler published a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggesting that proposed cuts to the NIH alone could translate into 82 million years of lost life (worth $8.2 trillion at $100,000 per a statistical year of life).

Cuts to grants and agency funding

The most controversial action by the Trump administration has been to cut science funding done by agencies like the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, both by terminating existing grants midstream, and by dramatically slowing down the issuance of new ones.

The most up-to-date resource shows that NSF has cancelled over 1,600 grants, worth around $1.5 billion. At the NIH, the administration has cancelled over 2,100 grants worth nearly $9 billion. In many (if not all) cases, DOGE is the agency that has made cancellation demands. There has been no reported involvement from anyone with scientific expertise. In some cases, the administration has apparently paused all existing grants awarded to specific institutions, including at Columbia, Harvard, Brown, Northwestern, and Cornell, often with no explanation (no one knows why Northwestern would be targeted).

Cuts have hit contracts as well as grants. In late March, DOGE ordered the NIH to cut its spending on contracts by around 35%, or $2.6 billion total, and to do so by April 8. As STAT reported, “NIH uses the contracts to employ not only IT workers and custodians, but also to repair specialized equipment and to hire additional scientists and technicians.” DOGE seems to have plucked that 35% number out of thin air, with no consideration for how these contracts are spent. As yet — and another point that bears repeating is how difficult it is to track all of this information — it is unclear what contracts NIH has cut or what the possible damage might be.

To be sure, everything is in such flux that on April 29, the Chronicle of Higher Education published an article titled, “These NIH Grants Were Terminated. Now They’re Back.” The article discussed several grants that had been terminated and then restored, without any court order or even any explanation to the researcher. One scientist quoted in the article said, “I’ve been asked by so many people, ‘What is the magic sauce? How did you get that grant back?’ And I’m like, ‘I have no idea.’” There are many other ongoing lawsuits, and the ultimate outcome is uncertain.

The administration has also made a sharp downturn in issuing new grants, as well as renewing existing ones, and has proposed dramatic and unprecedented cuts to virtually all science-funding agencies.

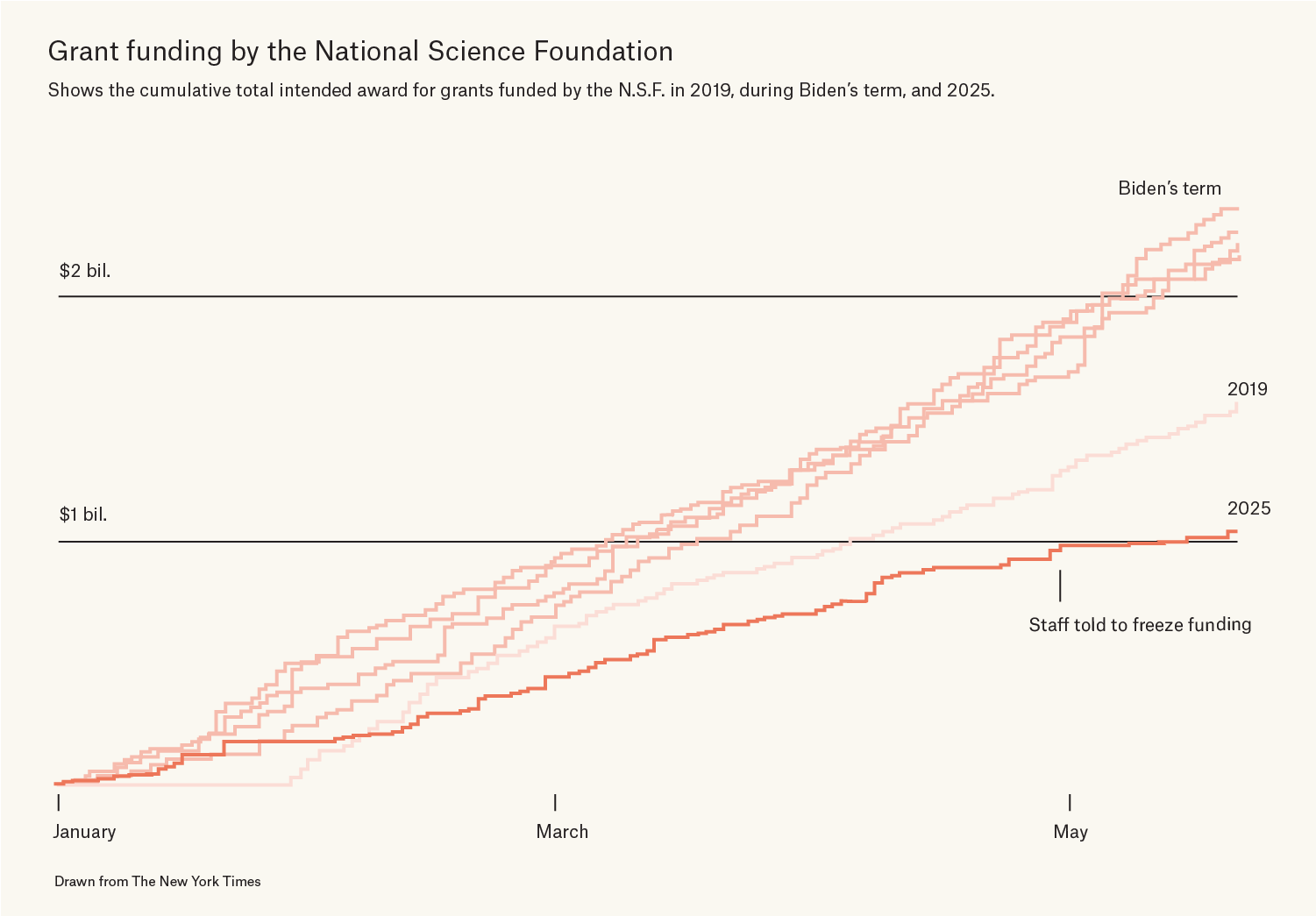

A May article in the New York Times documented the sharp cuts to the outflow of new grants by the NSF. For example, since 2015, the NSF has funded grants totaling $2 billion, on average, between Jan 1 and May 21. In 2025, that figure was $989 million, less than half. That is because on April 30, 2025, staff at NSF were told to “stop awarding all funding actions until further notice,” apparently for further review by political appointees.

It’s an even more extreme story at NIH. For example, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institutes of Mental Health have “awarded less than one quarter as many new extramural grants as they did over the same two-month period, on average, from 2016 to 2024.”

NSF has also cut its highly-acclaimed graduate fellowships by 50% — for no apparent reason. NIH has similarly frozen grants to many training programs, such as the ones issued by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (housed within the NIH), as well as many others.

One final wrinkle: In addition to cancelling existing grants and new grants, the administration also seems (at present) to be slow-walking renewals that would normally be forthcoming. The team at Grant Watch (as of late May 2025) found “1066 [grant renewals] which were 30 days overdue, 502 that were 60 days overdue, and 309 that were 90 days overdue.”

The new budget request for 2026

The administration’s stated reasons for cutting individual grants have predominantly centered on DEI, or the alleged offenses (not mutually exclusive) of a particular university, such as Harvard. But they are simultaneously asking for massive budget cuts to nearly every sector of science and R&D, most of which cannot possibly have anything to do with wokeness, DEI, or any particular university’s alleged flaws.

The administration is asking for an average cut of 55% across all of NSF. These cuts would impact basic biology, computer science, physics, nanotechnology, semiconductors, and virtually everything else that NSF does. The budget plan assumes that the number of research grant awards will drop from 7,300 per year to a mere 1,700, and that the number of people supported (including professors, post-docs, and graduate students) will drop from 330,100 to 90,000. That is a dramatic cut. It isn’t clear how most university science would even be able to function under such numbers.

Similarly, the administration’s budget request for NIH is $27.5 billion, only slightly more than half of the $48 billion allotted to FY2025. The budget request also assumes NIH has already been substantially reorganized.

They have also asked to cut NASA’s funding nearly in half. As Science reported, the new budget request would kill off multiple space missions (such as the Orbiting Carbon Observatories), and would end the Earth-facing instruments on the Deep Space Climate Observatory. It would also cancel “nearly every major science mission the agency has not yet begun to build,” such as the Atmosphere Observing System, the Surface Biology and Geology mission, and more.

One scholar created a chart showing the budgets of NIH, NSF, and NASA, since 2000 in inflation-adjusted terms. In every case, the Trump administration’s proposed 2026 budget is far below what those agencies received in 2000 or any year since.

Employee dismissals

In February, around 1,200 NIH employees were summarily dismissed by DOGE, for no reason other than being on “probationary” status – meaning that they had joined within the previous 2 years or recently been promoted. As soon as Jay Bhattacharya, the agency’s newest director, was confirmed, he publicly announced that he hadn’t been involved with any of the layoffs. He hopes, he added, to bring people back. Bhattacharya also ridiculed Elon Musk’s directive that government employees send a weekly email detailing the five things they had accomplished that week.

The state of NIH firings is in continual flux. For example, 30 employees at the NINDS were told on April 1 that they had been laid off, before being told 24 hours later that this was the result of a “coding error” and being asked to return to work. NSF is in even more dire circumstances. NSF leaders have privately told me that they are even more concerned about mass layoffs and their feedback effects, than they are about funding reductions. The NSF director, who was appointed by Trump in his first term, resigned in April, likely out of protest (DOGE had demanded he develop a plan to fire half of NSF’s staff). Even if the NSF budget is maintained in 2026 budget negotiations, at such a reduced workforce it would be unable to handle the workload and actually allocate the money.

Much may depend on the ultimate outcome from a major federal lawsuit out of California. Susan Illston, a federal district judge in San Francisco, issued a ruling on May 22, granting a temporary injunction against the administration’s overhaul. It stated that "agencies may not conduct large-scale reorganizations and reductions in force in blatant disregard of Congress's mandates, and a President may not initiate large-scale executive branch reorganization without partnering with Congress."

The government appealed, asking for a stay of her temporary restraining order. A week later, the Ninth Circuit issued an appellate ruling that denied that request. Among other things, the appellate court held that the Office of Management and Budget and the Office of Personnel Management have “only supervisory authority over the other federal agencies,” while “DOGE has no statutory authority whatsoever.” Thus, anything those agencies did to demand large-scale restructuring and firings were without any legal authority.

DOGE is to blame for many of the problems here. Despite its putative goal of government efficiency, many of its actions have had the opposite effect by adding layers of review in an effort to correct the misconception that the entire federal government is riddled with waste and fraud.

These procedural hurdles have struck at the heart of science funding in multiple ways. Nature has reported that a major reason for the unprecedented slowdown in NIH grant awards is DOGE’s insistence on reviewing grant approvals before they are finalized. An extra layer of grant review is the opposite of “efficiency.”

Moreover, DOGE has created an inordinate amount of confusion within agencies, which means employees waste time tracking down answers to questions they otherwise never needed to ask. As one NSF employee said, “There’s confusion on how much money we can spend. And then there’s confusion because the processes are basically paralyzed.”

For now, Congress’s appetite for challenging either the Trump administration or DOGE appears minimal. It’s possible that may change by the time this fall’s budget negotiations come around. Thousands of job losses are expected in almost every state, and elected officials may be feeling pushback. Congress will likely be more sensitive to such issues given that 2026 is an election year.

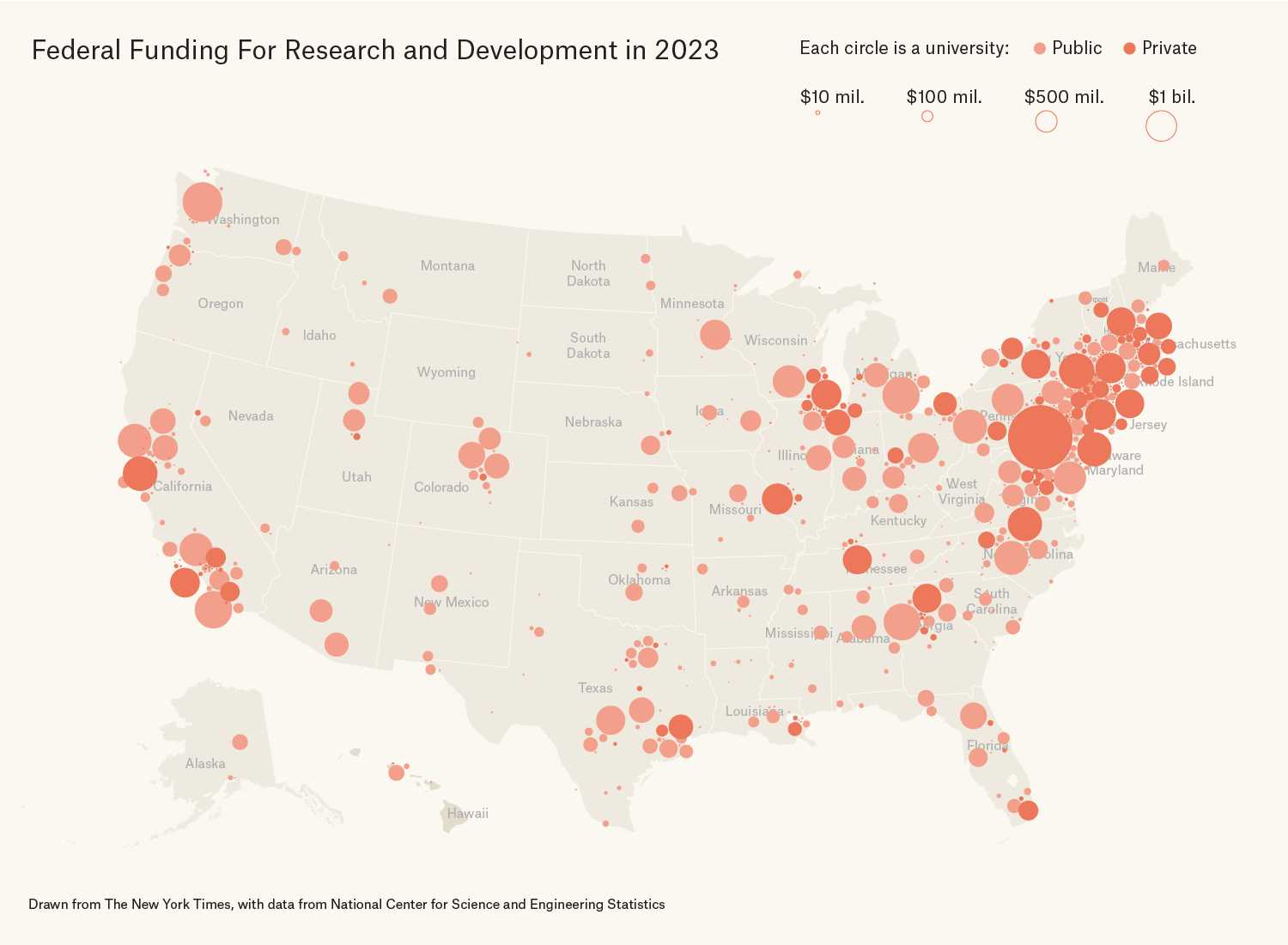

While a large proportion of federal research dollars flow to the typically more liberal states on the coasts, there is still substantial federal R&D spending that goes to universities in red states, including for instance Georgia Tech, Vanderbilt, the University of Florida, MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, the University of Texas, the University of Utah, and more. Florida State University, for instance, has announcedthat it is facing grant and contract cancellations of $102 million, and that “it is impossible for us to completely fill the gaps.”

Congressional Republicans across the country are unlikely to support drastic cuts to some of the most important employers in their home states. The March 2025 Continuing Resolution could provide an early indicator. Even though DOGE had been busy canceling grants and firing people for some two months, the Continuing Resolution (which handled the federal government’s discretionary spending going through Sept. 30, 2025) kept NIH’s funding at the same level as in 2024, at around $48 billion. No reductions.

And there are occasional murmurings of an uprising even among conservatives. One observer “said he has heard from even Republican offices on Capitol Hill that the budget is ‘dead on arrival,’” and that “no one is eager to cut NASA science. No one is out there openly defending and saying that this is a great idea.”

Immigration policy

Between the cuts to science funding and the immigration restrictions, many people worry that the US is going to abdicate its position as the world’s magnet for scientific talent.

The administration’s approach to immigration policy has been increasingly punitive and restrictive. In early April 2025, for example, journalists noticed that the administration had been cancelling not just student visas, but the students’ residency status within the Student Exchange and Visitor Information System . What did this mean? According to Inside Higher Education, terminating residency status would “pav[e] the way for arrest and deportation.”

The article quoted one university official who had “been working in the field for more than 40 years,” and who “said he’d never seen immigration services revoke a student’s SEVIS status before.” In many cases, the pretext seemed to be any legal violation whatsoever, including minor traffic offenses like running a stoplight years before. Over 280 colleges and universities had identified more than 1,800 international students who were targeted by the Trump administration for visa revocation, often for offenses as minor as turning right on a red light.

Dozens of lawsuits ensued. In one court case, DHS told the judge that this was because they had asked employees to run 1.3 million names for any possible legal charges, leading to around 6,400 findings. In other words, there was some significant desperation to find any violations anywhere, no matter how insignificant. As Politico found, “many of those hits flagged students who had minor interactions with police — arrests for reckless driving, DUIs and misdemeanors, with charges often dropped or never brought at all — far short of the legal standard required to revoke a student’s legal ability to study in the U.S.”

But then, in a surprise, DHS told one court that the agency doesn’t even “have the authority to terminate students’ immigration statuses by terminating their records in the Student Exchange and Visitor Information System.” As of April 25, 2025, it was reported that the administration had backtracked on the cancellation of residency status in the SEVIS system. No wonder: by that point, there were actually “50 restraining orders from dozens of federal judges.”

Most recently, the State Department announced a new policy for screening the social media posts of applicants for student visas. Specifically, officers are supposed to look for “any indications of hostility towards the citizens, culture, government, institutions or founding principles of the United States.” Of course, there’s a difference between admitting a Hezbollah member who regularly posts “death to America” and admitting a Chinese or Indian student who has posted skepticism about the current US government’s policies towards science, but for all we know, the latter might equally count as “hostility” towards our “government.”

In the case of Harvard, which has become the figurehead of university resistance — and the administration’s favorite enemy — a letter was sent in late May 2025 threatening to cancel Harvard’s ability to enroll international students, of which there are currently around 6,800. The pretext for the letter was that Harvard had failed to provide sufficient disciplinary records and videos of protest activity as to any international student going back five years. The administration’s action was immediately put on hold by a federal court, but as in so many cases mentioned above, it all depends on what appellate courts (and perhaps the Supreme Court) ultimately say.

Conclusion

While this is admittedly speculative, a number of private conversations in DC have made me hopeful that Congress will eventually come up with the energy to push back against all the drastic cuts. It’s one thing in early 2025 to play along with DOGE and the White House’s early cost-cutting approach, while saying it was to push back against the now-departed Fauci or the Biden-era focus on DEI or “woke” initiatives. It is another thing entirely for Congress to agree to forward-looking cuts of 50% while going into an election year. If nothing else, federal R&D supports many hundreds of thousands of jobs, including some of the largest employers in rural areas. Members of Congress want to be reelected at the end of the day, and the Constitution gives them the power of the purse. They may well decide to be more forceful in using it.

Still, for all the sturm und drang, the administration’s actions to date are just a small foretaste of what they intend. The loss of personnel, foreign students, and post-docs might ultimately be the most important factor. Funding science is only theoretical if we don’t fund the personnel who hand out science funding or the personnel who work in labs across the country.