“It may be readily surmised that where the best thinkers have failed to produce an unexceptionable classification, the failure must be due to some inherent difficulty of the subject.”

— Edward Charles Spitzka, Insanity: Its Classification, Diagnosis, and Treatment (1883)

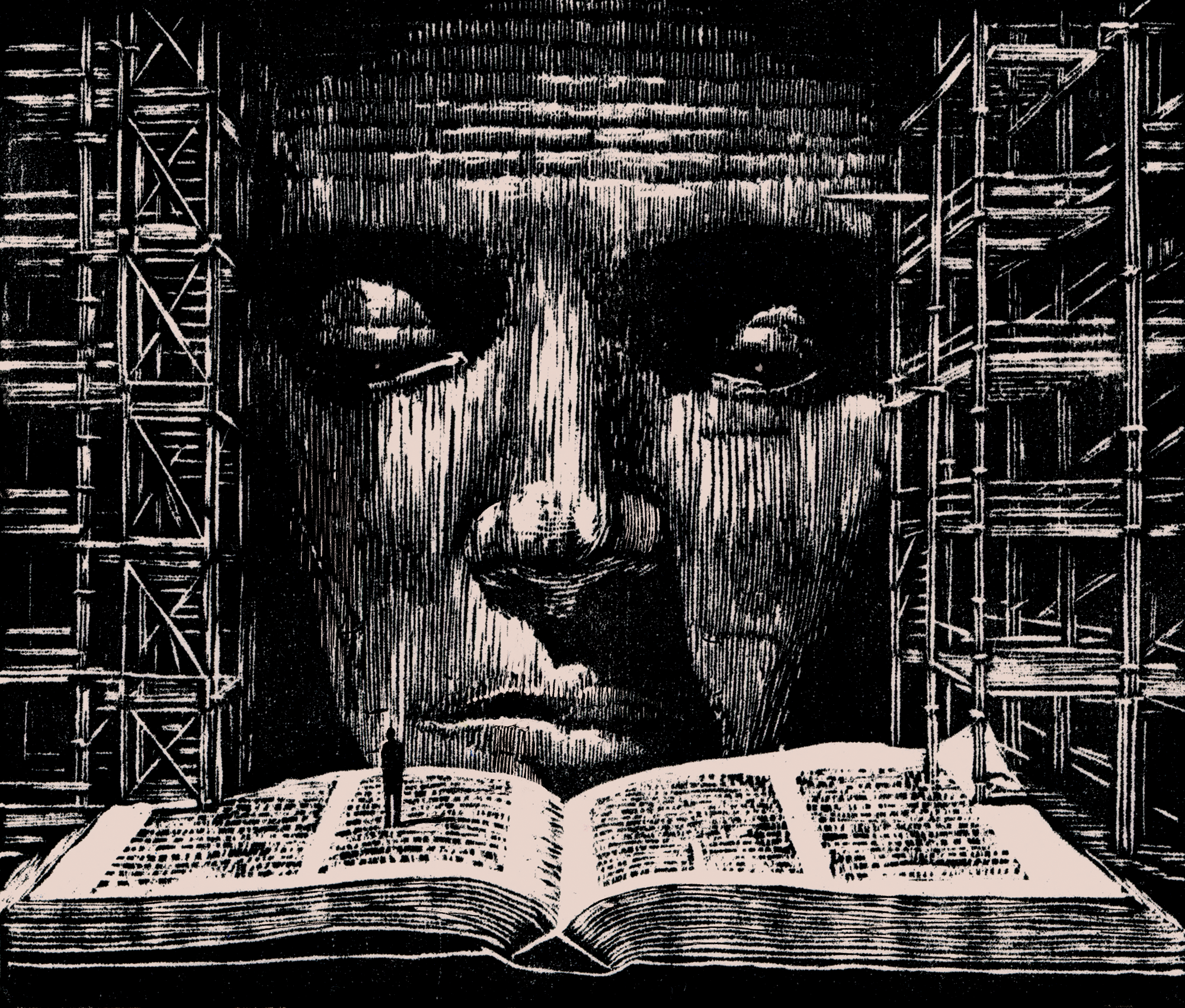

In his 2013 essay “Book of Lamentations,” cultural critic Sam Kriss reviews the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as if it were a work of dystopian literature, a kind of nightmarish encyclopedia in the lineage of Borges. Kriss argues that the manual is a literary object with a deeply unreliable narrator, who writes with a coldly compulsive voice that cannot perceive its own madness. “As you read, you slowly grow aware that the book’s real object of fascination isn’t the various sicknesses described in its pages, but the sickness inherent in their arrangement.” The idea that the focus on DSM-style classification might itself be a symptom of pathology has trickled into pop culture since then. A 2018 headline in The Onion, “American Psychiatric Association Adds ‘Obsessive Categorization Of Mental Conditions’ To ‘DSM-5’,” reads as a punchline to Kriss’s argument.

Kriss sees the DSM as a device of absurdity and detachment because he reads it as making assumptions that are not explicitly present in the book itself: that madness is internal, individual, and biologically determined. The DSM’s silence on these issues does little to dispel this interpretation. But it would be more accurate to say, as psychiatrist John Sadler does in his book Values and Psychiatric Diagnosis, that “the DSM is decontextualized and decontextualizing only if it is split away from the context of good clinical practice.” It's not until a clinician steps in, ideally someone attuned to the nuance and idiosyncrasies of human experience, that the diagnostic categories and criteria in the DSM acquire their context.

If literary provocation offers one way to wrestle with the DSM’s contradictions, my own instinct is to reach for the Greek myths of punishment. Sisyphus, Tantalus, and Prometheus are each good candidates, but perhaps the most apt is the Danaids — the fifty daughters of Danaus who were condemned to the underworld, forever carrying water in jars riddled with holes.

Since its first edition in 1952, the DSM has gradually evolved from a slim document meant to standardize psychiatric recordkeeping into a sprawling classification system that shoulders a set of responsibilities it was never designed to bear. It is expected to guide clinical care, enable research, satisfy insurance companies, anchor epidemiological studies, shape patient self-understanding, and serve as a platform for public policy. Each of these demands pulls the manual in different directions.

Like the Danaids’ jars, diagnoses leak relevance and accuracy as they move across contexts. And yet — the task goes on, because clinicians still need a shared language, insurers still need billing codes, governments still need their statistics, and researchers still need clear descriptions of who to enroll in clinical trials.

The first serious attempts to design psychiatric diagnostic systems were made in Europe. One of the most influential was created by Emil Kraepelin, a German psychiatrist who developed a way to group mental illnesses based on shared symptoms and how each condition progressed over time, which he presented in nine prominent psychiatry textbooks published from 1883 to 1927. Kraepelin was an academic physician engaged in a scientific project of classification, akin to — he hoped — other natural sciences. He was also a skilled clinician who aimed to provide practical guidance. He worked in a period when asylum populations were expanding and argued that more clinical data and better classification could support public health planning.

His categories lent themselves to recordkeeping and eventually fed into the bureaucratic machinery that tracked asylum patients.

In the United States, early classification systems were shaped by the practical needs of managing larger, state-run asylums, which dramatically expanded over the first half of the 20th century. In 1918, a guide called the Statistical Manual for the Use of Hospitals for Mental Diseases was created by the American Medico-Psychological Association and the Census Bureau. It was meant to standardize data collection across hospitals, but didn’t include clear definitions or criteria for diagnoses.

World War II served as the catalyst for what would become the first edition of the DSM. Influenced by Swiss psychiatrist Adolf Meyer’s theory of psychobiology, which would reshape psychiatry in the years to come, military doctors had come to understand that otherwise ordinary individuals could develop lasting mental health problems under extreme stress. Meyer’s ideas were a key influence on a 1943 document known as the “War Department’s Technical Bulletin, Medical 203.” Medical 203 marked the first time that the military recognized that systematic, standardized psychiatric classification was essential for managing large-scale mental health challenges. When the American Psychiatric Association

moved to publish its own manual, DSM-I, in 1952, it relied heavily on Medical 203’s framework and terminology.

DSM-I was shaped by many hands, including military psychiatrists, public health experts, and psychoanalysts. It mostly reflected the psychological thinking of the time — that mental disorders were reactions to life stresses or interpersonal conflict, not biologically rooted diseases. The first manual included 106 disorders, though its definitions were kept vague. It also gave little consideration to whether doctors would be able to make and use the diagnoses consistently. Still, DSM-I established the American Psychiatric Association as the central voice in psychiatric diagnosis, paving the way for future editions. Over the next 70 years, it would be revised every one to two decades

In the postwar decades, American psychiatry became dominated by Freudian ideas. DSM-II, published in 1968, was eclectic in influence but emphasized concepts like “neurosis,” capturing the psychoanalytic idea that unconscious conflicts and defense mechanisms gave rise to symptoms. Because psychoanalytic theory emphasized continuums and peculiarities of individual psychological development, the classifications in the second edition remained loose — and not particularly important. Diagnoses like “anxiety neurosis” or “depressive neurosis” were common, but they weren’t meant to sharply distinguish one state of illness from another.

The 1960s and ‘70s saw the rise of the antipsychiatry movement. Critics from within psychiatry, like Thomas Szasz and R.D. Laing, from academics such as Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze, and from civil rights activists, accused psychiatry of pathologizing everyday behavior, classifying deviations from social norms as if they were medical disorders. One major point of contention was the inclusion of homosexuality as a mental disorder, which led to organized protest and its eventual removal from DSM-II in 1973.

Distrust in the system that used the manual was not without cause. It was already clear in the mid-20th century that psychiatry faced a crisis of reliability. As early as 1949, a pre-DSM-I study found that three clinicians agreed on a specific psychiatric diagnosis only 20% of the time; even on the major category of disorder, each agreed only 45% of the time.

Regular reports of international diagnostic discrepancies prompted the creation of a cross-national project. A 1971 study from that project, led by Robert Kendell and colleagues, is the most famous. It was conducted using videotapes of unstructured diagnostic interviews with eight patients. Serious disagreements arose in some cases where the majority of American psychiatrists gave the diagnoses of schizophrenia, while the majority of British psychiatrists diagnosed either manic-depressive illness, personality disorder, or neurotic illness.

There was also the fact that it appeared trivially easy to feign serious illness. Inspired by a lecture given by Laing, David Rosenhan led a famous experiment in which eight healthy volunteers, in addition to himself, presented at various hospitals with minimal, fabricated symptoms of auditory hallucinations. In a 1973 paper in Science, “On being sane in insane places,” he described the results. All were admitted, each diagnosed with schizophrenia or manic-depressive psychosis and treated with antipsychotics — despite behaving normally after admission. The study is now known to be largely fraudulent, thanks to investigative journalism by Susannah Cahalan, but at the time it highlighted the fragility of psychiatric diagnosis, both at the level of specific categories like schizophrenia and at the level of “mental disorder” itself.

Another movement within psychiatry looked to the field’s past. Emil Kraepelin had believed that mental illnesses were distinct, biologically based conditions that could be identified by a predictable mix of symptoms and physical or genetic markers. His late-20th century followers, often called neo-Kraepelinians, revived this idea in the 1970s and ‘80s. Eli Robins, Samuel Guze, and other psychiatrists examined the associations between symptom clusters and factors like family history, various laboratory markers, and course of illness to determine whether symptom-based diagnoses were connected to other medical information.

All of these pressures culminated in the heavily revised DSM-III, released in 1980. Led by Columbia University psychiatrist Robert Spitzer, DSM-III abandoned psychoanalytic ideas and adopted a symptom-based model to align more closely to the diagnostic practices of general medicine. Spitzer built heavily on the “Feighner criteria,” the first systematic set of operationalized rules for the psychiatric diagnosis of 15 conditions, introduced in 1972. For the first time, disorders were classified by a list of specific symptoms, including severity and time thresholds — a step forward from Kraepelin’s system, which didn’t have operationalized criteria for different conditions. These changes made it easier for different doctors to agree on a diagnosis and for researchers and insurance companies to use the manual.

“Anxiety neurosis” in DSM-II, for example, was simply described as “characterized by anxious over-concern extending to panic and frequently associated with somatic symptoms… anxiety may occur under any circumstances and is not restricted to specific situations or objects.” Compare this to the current version of the DSM, where criteria for generalized anxiety disorder require “excessive anxiety and worry” occurring “more days than not” for “at least six months” and accompanied by three or more symptoms out of six: restlessness, easily fatigued, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbances

. In addition, these symptoms must cause “clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning.”

Thus DSM-III marked a new era in psychiatry, one that emphasized descriptive operationalization and practical use. It also reflected a growing belief in the profession that mental illnesses should be seen as diseases of the brain, rather than reactions to life circumstances or manifestations of unconscious mental conflicts, though the manual itself did not officially take any position on this matter.

The next editions continued to refine and expand the symptom-based model. The 1987 DSM-III-R (for revised) aimed to fix inconsistencies and allowed for multiple diagnoses at once, while 1994 DSM-IV incorporated field trials and evidence-based reviews.

As it became more systematic, the DSM also grew in size. There were 106 diagnoses in DSM-I and 182 in DSM-II. According to Blashfield and colleagues (2014), there were 228 diagnoses in DSM-III and 383 in DSM-IV — out of which 201 had defined diagnostic criteria.

As the number of diagnoses grew with each edition of the DSM, so did professional and public criticism. Some argued that the manual was over-pathologizing normal behavior. Conditions like ADHD, autism, and bipolar disorder were diagnosed at higher rates than had been expected, sparking debates about overdiagnosis, and where and how a clinician should draw the line between normal and disordered. The sociologist Allan V. Horwitz, for example, notes: “Community studies based on the DSM-III criteria had estimated the lifetime prevalence of bipolar conditions at 1–2 percent of the population. Studies using the DSM-IV criteria indicated that far more people were bipolar in any single year than previous lifetime estimates.” The DSM-IV task force had similarly estimated that changes in autism criteria would only modestly increase prevalence, but the rate actually increased more than 16-fold, from 1 in 2,500 to 1 in 150 over a decade.

In advance of the DSM-5, there were hopes for a “paradigm shift” which would incorporate findings from neuroscience and create a more dimensional, biologically based system.The neo-Kraepelinians had believed that with iterative research, biological validators would point towards the hidden disease entities, in much the same way that syphilis had been identified in the early 20th century as a cause of a then-common condition “general paralysis of the insane.” But by the 1990s, it was becoming obvious to scientists that validators of DSM categories did not converge in any neat fashion. For example, while data from relatives suggested that schizophrenia was a broad spectrum of conditions, looking at patients’ prognoses suggested it was a more narrowly defined illness. Many of the genes associated with schizophrenia were also associated with conditions such as bipolar disorder and autism, and changes in brain circuitry were neither uniformly present nor specific to the disease. Some percentage of people with schizophrenia might even have an undiagnosed autoimmune illness — we do not quite know how many. The idea that many conditions are hiding within the syndrome of schizophrenia has a long history; in fact, Eugen Bleuler, the psychiatrist who coined the term “schizophrenia” in 1908, described it as “the group of schizophrenias.” There isn’t one tidy answer.

The developers of the DSM-5 had no new paradigm to offer. Internal disagreements within the profession, public criticism, and scientific limitations led to a rather cautious and conservative update. In particular, the manual stuck to its traditional categorical format. (Among the changes that did happen was a shift from Roman to Arabic numerals in the title of the book.)

Like earlier editions, the DSM-5 came under fire for pathologizing ordinary emotions. Allen Frances, the chairman of the taskforce that had developed DSM-IV, accused DSM-5 of out-of-control medicalization. He called the publication of DSM-5, “the saddest moment in my 45 year career” and urged his colleagues not to buy, use, or teach the manual (quoted in Allan V. Horwitz's DSM: A History of Psychiatry’s Bible (2021), p 143.) In fact, the DSM-5 is objectively very similar to the DSM-IV, but its few changes were often high-profile and fiercely debated. Alterations like removing the exception for a two-month period of grief for a diagnosis of major depression and expanding autism into a spectrum became symbolic targets for anger over the perceived pathologization of everyday life.

The APA also came under scrutiny for potential conflicts of interest. The APA owns the DSM and earns revenue from its sale and license — some several million dollars a year — while also controlling its content. Furthermore, 57% of DSM-IV task force members and 69% of DSM-5 task force members had financial associations with the pharmaceutical industry. Whether and how these potential conflicts influence decisions about diagnoses remains contested and undetermined, but the relationships continue to be a source of mistrust.

And then there were the scientific critiques. Thomas Insel, then director of the National Institute of Mental Health, distanced the NIMH from the manual. In a scathing public statement, he stated that the DSM lacked scientific validity, that “patients deserve better,” and announced a new research initiative, the Research Domain Criteria, which aimed to base diagnosis on genetics and neuroscience.

A few years later, another scientific alternative emerged from a grassroots consortium of quantitatively-minded psychologists — Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology, or HiTOP — which was focused on describing statistical patterns of symptoms across populations.

DSM-5 became the symbol of a deep tension within the field. Psychiatry wanted to be seen as part of clinical neuroscience, but didn’t yet have the evidence to fully support that shift. The controversy around DSM-5 also hurt its public image. While it remains the go-to manual in practice — since no alternative has been able to displace it — it no longer carries the same unquestioned authority.

The realization that psychiatric disorders had no neat biological explanation opened the door for critics who argued that diagnoses are sociocultural constructions. Antipsychiatry critics such as Bonnie Burstow, following Thomas Szasz, have maintained that psychiatric diagnoses function as tools of social control and it is no surprise that we have failed to discover their biological basis. Philosopher Ian Hacking introduced the idea of “looping effects,” the notion that once people are diagnosed, they start to change in response to the diagnosis itself, which in turn changes future classifications. Unlike insects or diseases, people behave differently when they know they are being labeled.

Still, the skeptical social-constructionist view also has its limits. Yes, mental health categories are influenced by culture, and the patterns we see can be described in different ways, but that doesn’t mean symptom patterns have no relationship to biological processes. Even if genes or brain scans do not line up with DSM categories, researchers have found plenty of evidence that biological processes such as genetic factors, inflammation and brain circuitry are involved in mental illness. These patterns aren’t random or meaningless; they’re just far more complicated and messier than we had hoped. “Biology never read that book,” Thomas Insel famously said about the DSM.

Once we relinquish the idea that diagnosis must “carve nature at its joints,” the DSM is revealed for what it is: a practical, serviceable tool. It doesn’t capture whatever distinctions exist among the causes and mechanisms of mental disorders, but it does describe meaningful patterns of symptoms. Across large groups, diagnostic categories correlate with differences in trajectories, treatment responses, personality traits, and physiological processes, but it is also abundantly clear that these syndromes are not disease entities, like Rubella or Huntington’s Disease — illnesses with a defined cause, set of characteristics, and distinct course. Psychiatric disorders are, in the stark words of psychiatrists Bruce Cohen and Dost Öngür, “heterogeneous in all ways and at all levels studied, in cause, mechanism, and expression of illness.”

All this would be manageable if only psychiatrists read the DSM. But another strand of discontent centers not on science or treatment outcomes, but on the DSM’s sociocultural impact — how it has reshaped our relationship to our own inner lives.

The psychoanalyst Nancy McWilliams captures this concern with unusual clarity in her 2021 essay “Diagnosis and Its Discontents.” She reflects on a shift that began with the release of DSM-III, when psychiatry embraced a more descriptive, symptom-based diagnostic model. The change, she notes, quietly restructured how people speak about themselves in therapy. Once, a client might enter the room and say, “I’m painfully shy and I’d like help relating better to others.” Today, a similar person is more likely to announce, “I have social phobia,” as if an unwelcome and alien force had colonized an otherwise intact psyche.

All it means for a person to “have,” say, generalized anxiety disorder in the DSM sense is for the anxiety to meet certain thresholds of severity and duration, and to negatively impact a person’s life. What that means for the state of one’s biology or for one’s self-understanding is both scientifically and philosophically unsettled. And yet, in the new clinical, atomized, and oddly impersonal idiom, “having OCD” or “having ADHD” invites one to imagine essences within oneself that do not exist. This linguistic shift, McWilliams observes, often accompanies a deeper psychological distancing. People present themselves as hosts to diagnostic entities, rather than agents struggling through difficulties. In the most extreme cases, that essence becomes all-pervading, a core of who they are.

The DSM was never crafted with the purpose of helping individuals make sense of their own psychological struggles, nor is it particularly well-suited for that task. The DSM is a tool for clinicians and researchers. It presumes a baseline of clinical training and medical knowledge, and an appreciation of methodological limitations. It is not a guidebook for laypeople navigating their inner worlds.

Yet the DSM’s design seems to invite this kind of lay appropriation. Its apparent clarity, readable prose, and approachable format disguise its status as a technical document. Sadler notes that, in contrast to the DSM, the International Classification of Diseases by the World Health Organization rarely becomes the butt of jokes or fodder for op-eds. That may be because the ICD wears its technocratic nature on its sleeve: dry, dense, and unmistakably aimed at professionals. The DSM, with its deliberately “user-friendly” format and preference for everyday language, appears vulnerable to misinterpretation by the public.

In Categories We Live By, psychologist and author Gregory L. Murphy discusses how people tend to believe that certain categories are grounded in something deep, some hidden property that gives the category its identity, even if they cannot say exactly what that something is.

Psychologist Woo-kyoung Ahn and her colleagues at Yale have explored how this kind of essentialist thinking plays out in the realm of mental illness. Their studies reveal that laypeople tend to see psychiatric categories as more “real” and more unified than clinicians do. If someone has a particular DSM diagnosis, then they imagine that there must be some internal “thing” responsible for the illness, something that is shared across all cases. Experienced clinicians and professionals, on the other hand, are less likely to think that way.

The psychologist Eric Turkheimer has commented that psychiatric diagnosis is a “relief from the Sisyphean burden of understanding the relationship between our bodies and our intentions.” It’s exhausting to ask, again and again, why we suffer so intensely, despite our efforts to feel otherwise, or why we return to self-destructive habits even when we know better. Our struggle with these questions leaves us emotionally depleted. If calling these struggles “disorders” offers a kind of balm, a way to temporarily suspend the ambiguity, then maybe that’s a mercy.

The writer Lauren Oyler arrives at the opposite verdict, at least as far as she herself is concerned. In her essay “My Anxiety,” she describes how the bureaucratic dance of diagnosis and treatment seems so fraught, so burdened with hidden costs, that it feels not just unhelpful but actively undesirable. As she puts it:

I do not want to have these problems that are notoriously difficult to solve, about which there is no professional agreement. I do not want to embark on a years-long project dedicated to my own mind… I do not seek a diagnosis, probably, because I do not want to be trapped in a single term… Like everyone else’s, my mind dabbles in an array of mental illnesses to create a bespoke product, and I find all the terms I know either ludicrously broad or ludicrously specific.

Her resistance is against an epistemic narrowing of the self. Where in Turkheimer’s perspective diagnosis offers a reprieve, it offers only confinement to Oyler. She doesn’t want to be cornered by language, to have her fluctuating experiences pinned under a diagnostic term. This resistance, however, shows just how powerful those terms can be. We seem to need them for our suffering to feel real, and yet we bristle when they confine us.

There is a temptation to think that all these troubles stem from the DSM itself, that if only we could replace it with something more scientific — say the HiTOP system proposed by more quantitatively oriented scientists — then the relationship between diagnosis and self would no longer be so thorny. The error here is that we are conflating two fundamentally different enterprises. Psychiatric classification as a clinical and scientific project is not designed as a tool for existential self-definition. It is not for you. No diagnostic manual can tell people who they really are.

Psychiatric conditions are surely relevant to who a person is. If someone struggles profoundly with social communication and engages in repetitive behaviors, recognizing that this pattern exists will unavoidably shape their view of themselves. The same is true for someone who has lived with sustained difficulties in attention, or recurring psychotic episodes, or the pendulum of mania and depression. But recognizing that is not the same as anchoring those experiences in checklists, or presuming that they map neatly onto singular disease mechanisms, or that their inclusion or exclusion from a diagnostic handbook confers them greater or lesser meaning.

One of the controversies during the development of DSM-5 was that the diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome, a form of high-functioning autism, was subsumed into the broader category of autism spectrum disorder. A vibrant community had organized itself around the identity of Asperger’s and many felt that their identity was being taken away when the category was eliminated. The debate around Asperger’s syndrome should have sparked a collective realization: that the sense of self shared by those who identify as “Aspies” never needed to hinge on whether the DSM retained that term. How can a medical manual, subject to change, driven by evolving criteria, have the authority to define or dissolve a social identity? Social identities live and die on their own terms.

In my own clinical work, I often find myself attempting to deflate the power of these categories. I remind patients not to lean too heavily on the label I’m offering. Not because the label is meaningless, but because the problems it captures are typically imprecise, shifting, deeply contextual. I describe symptom patterns in relation to broader psychological structures, early experiences, temperament, and life stressors.

My hope in these conversations with patients is to plant a seed of resistance, to offer an account of suffering that acknowledges complexity, contingency, and context beyond categories. I try to say, in effect: this pattern of symptoms reflects something meaningful about your psychological life, but it doesn’t define you. It shouldn’t be the scaffold upon which you build your entire self. You’re free to acknowledge it, even to use it as a lens, but don’t let it confine you. Do not let it determine your story.

And yet, I am aware that at a certain level this message is deeply unsatisfying, both to those who see diagnosis as a scaffolding and to those who see it as a trap. In gesturing toward the messy interweaving of temperament and trauma, and softening the solidity of diagnoses, I refuse to indulge our strange masochistic desire for categorical self-confinement.

The work of self-definition, especially in the presence of mental illness, is profoundly difficult. The challenge is so enormous that it exhausts us — and DSM categories, imperfect and unsuitable for this task though they are, are nonetheless, for many, a welcome respite from the burden.