Middlemarch demanded extra effort from me as a reader. The difficulty wasn’t in the reading, but rather the mechanics of turning each page. And that’s on me — I accepted the challenge when I bought it.

Like most book collectors, I approach my purchases with neurotic fastidiousness.

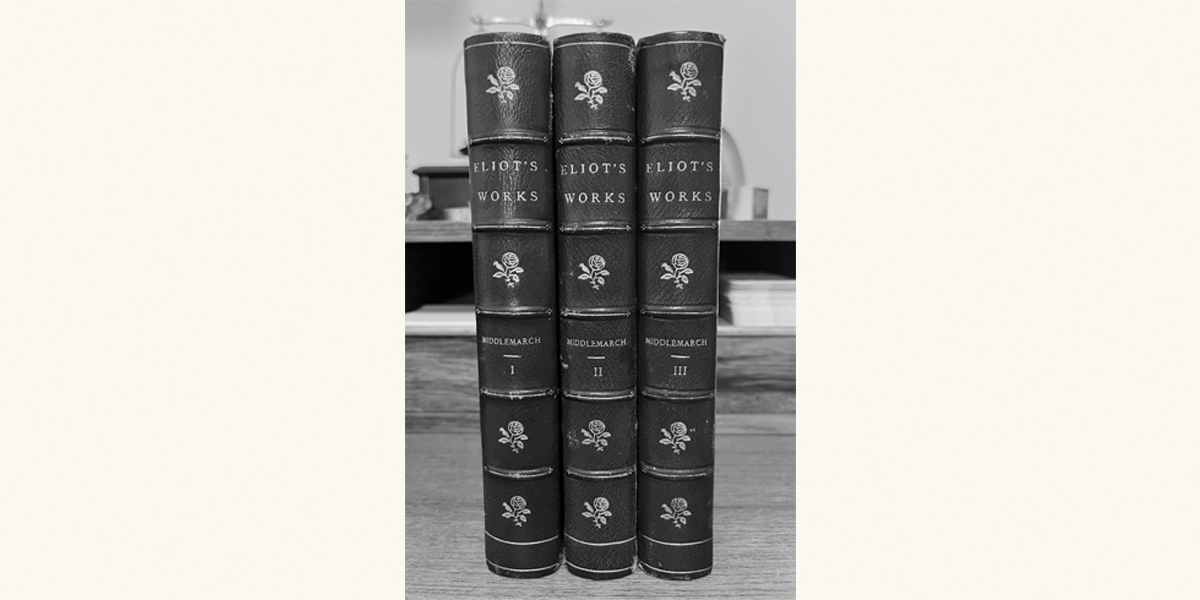

I had recently read and loved three of Eliot’s other novels, so it was a good bet I’d love what is universally acknowledged as her masterpiece. And so, to heighten and consecrate my experience of the book, I hunted for a special edition. As with a well-chosen picture frame, the physical form should elevate the content, and I also wanted it to evoke Eliot’s time period.

Eventually I found the ideal copy: a three volume illustrated octavo edition, beautifully bound in maroon half-leather.

It had kaleidoscopic marbled endpapers and gilt rose motifs on the spine. But the real coup wasn’t the binding. As the bookseller had specified at the end of the listing, the pages of this copy were unopened.

That’s where the extra effort came in. When this particular book was made, individual pages were first printed on larger sheets. A single sheet would have had eight pages printed on each side. The binder then folded and gathered these sheets into what is called a signature. The signatures were then stacked and sewn together at the spine. You can still see these gathered signatures in many new books if you tilt a closed book towards you to look where the pages meet the spine.

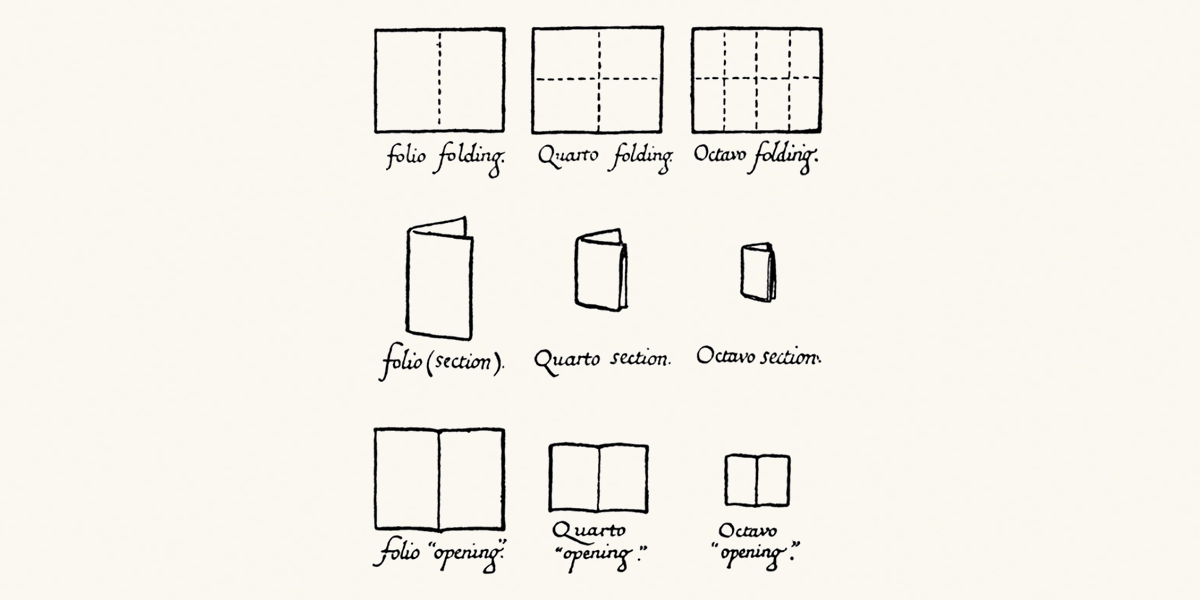

To understand why pages might be inserted unopened, an image is helpful:

With a folio, the fold rests against the spine, so the edge of the book will have no unopened pages. In a quarto, the pages are fused at the top, while in an octavo, some will be fused both on top and on the fore-edge. (You can see this yourself if you fold a piece of paper in half widthwise, and then twice lengthwise.) The pages remain fused until and unless the binder cuts them with a “guillotine” or a “plough.”

As late as 1920, books could be purchased with unopened pages. Avid readers often kept a dedicated book knife for this purpose, although a sturdy bookmark will do the trick for all but the thickest paper.

What this told me about my book — undated but probably from around 1900 — was that despite being at least a hundred years old, I would be the first person to read it. (Historians suspect Darwin never read Mendel, citing among other evidence that the only text in Darwin's library that discussed Mendel's experiments had unopened pages.) Every few pages, I carefully slid my bookmark along the folded edge, separating the pages and revealing the virgin text.

No matter how much care I took, an occasional cut went wrong, leaving a ragged edge or a tear. As it should be. This book was mine. I played a role, however small, in its creation by disclosing its hidden pages to the world.

Mindful care and effort create meaning. The ritual of splitting those folds, over and over, established a personal relationship between me and Middlemarch. It invested those three volumes with an aura, further strengthened by the respect I extended to the delicate Morocco leather binding. I took care when sliding the volumes in and out of my bag. I checked that tables and counters were clean before I put the books down. I made a sacrifice — my time, my attention — and in doing so cast a spell of significance, not unlike that which infuses a handwritten note or a homecooked meal.

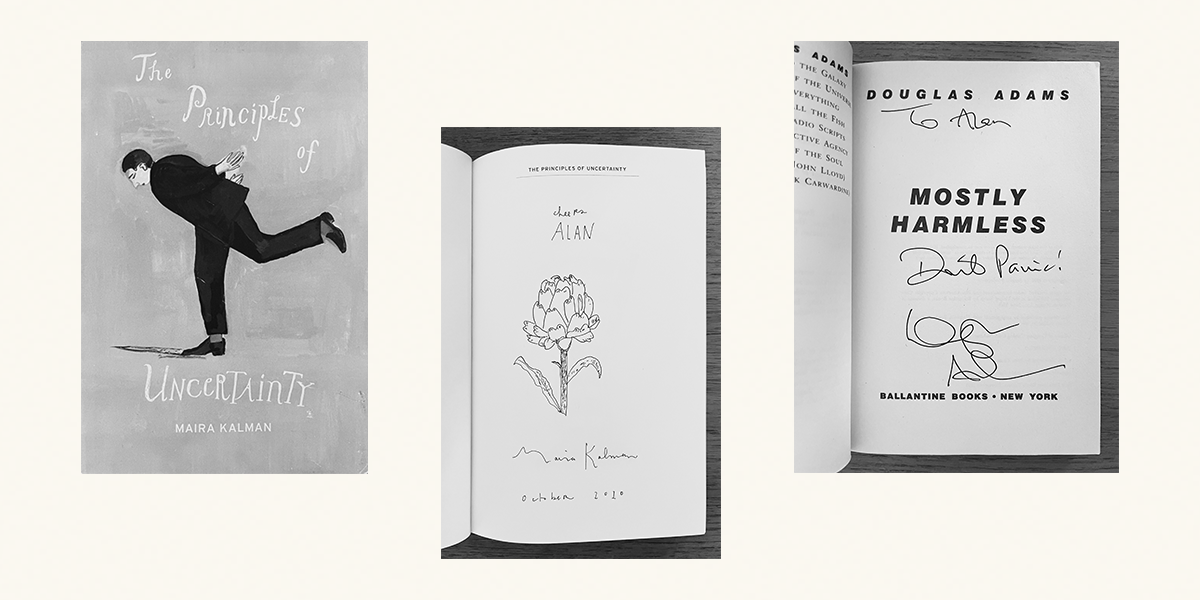

There are countless other ways to enchant physical books, the most popular of which is getting one signed. The ink acts as a portal back to a specific moment, commemorating the intersection of an embodied human and a book.

And so it is that my signed paperback copy of Douglas Adams’ Mostly Harmless — “To Alan, Don’t Panic! Douglas Adams” — whisks me backwards 31 years, and suddenly I’m thirteen with my best friend in the back of his family’s Mercedes, his mother swerving around cars at top speed, holding a giant wired carphone (so cool!) in one hand, begging the bookstore to ask Douglas Adams to please stay just a bit longer because she’s gotten caught in traffic, and yes she knows the talk has ended, but these boys will be just devastated, and minutes later staring up at my hero, a gentle giraffe of a man, who grins and graces my book with the most famous phrase he’s written, knowing that for the last fifteen minutes we’d been panicking like crazy.

Holding the book, even just seeing the spine on my shelf, I feel a rush of his kindness and calm.

I frequently reach out to authors and illustrators whose work is meaningful to me, and ask if they’re willing to enchant (I say “sign”) my books. If they are, as Maira Kalman once was, I send the book their way with a pre-paid, self-addressed envelope and an earnestly effusive thank-you card. The card I sent to Kalman had an artichoke on it, which I wouldn’t otherwise remember but for the fact that she drew a version of that very artichoke smack in the middle of her whimsically lettered inscription.

Kalman is exquisitely attuned to the magic of physical books. In fact, she includes the instructions and ingredients for another type of spell in The Principles of Uncertainty.

Attached on a perforated edge is a folded map of the world, drawn by her mother. “Either put it on the wall,” suggests Kalman on the map’s reverse, “or put it back into the book. If you put it back into the book, it may one day fall out when someone browses through the book and it will become a thing that falls out of a book.”

I removed it, opened it, and returned it to the book. Other copies will be missing it. New ones (and maybe some used ones) will have maps that are still attached, unopened like the pages of my Middlemarch once were.

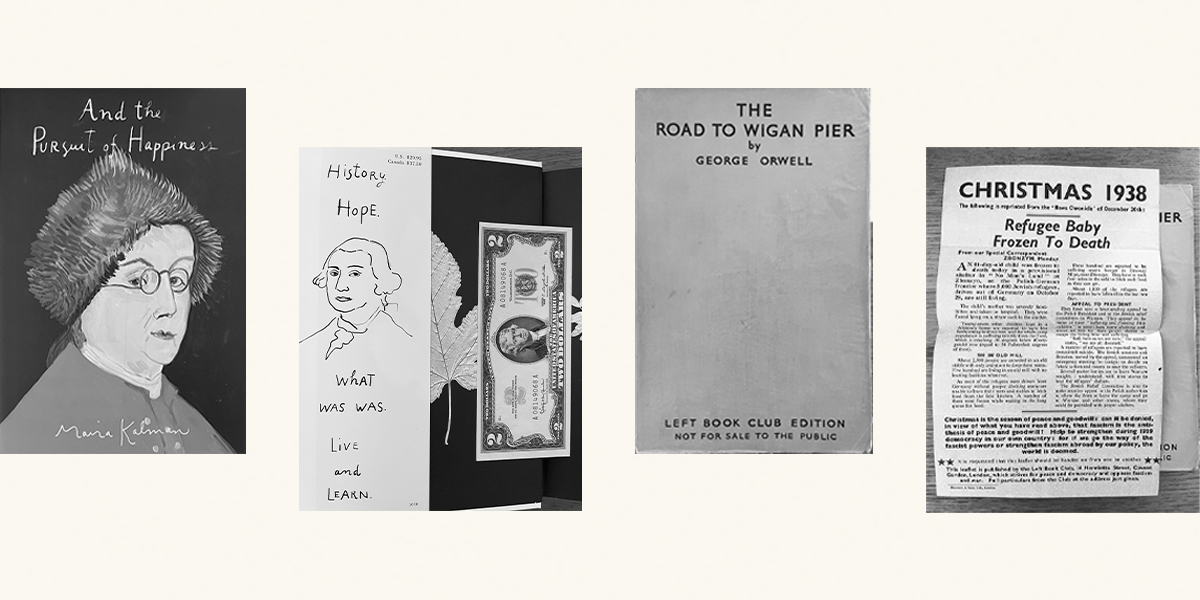

Serendipitous encounters with ephemera are my favorite form of book magic. I’ve hidden some sort of treasure in virtually all of my books: postcards, playing cards, birthday cards, notes, scraps, anything (flat) of symbolic significance that resonates with content. There the objects lie in wait, building synchronicity, ready to transform into charms when some lucky reader releases them.

A long time can pass before I pick up the same book again, allowing me to practice this magic on myself. It happened just now, when I took another Kalman book off my shelf, And the Pursuit of Happiness, her exploration of the Founding Fathers. Tucked inside by prior Alan was a pristine two dollar bill, Jefferson’s engraved face giving me a green Mona Lisa smile, just opposite Kalman’s portrait of him on the jacket flap. I live in Charlottesville, a few miles from Monticello. Some eccentric resident honors his legacy by paying for everything they purchase in town with crisp two dollar bills.

Enchanters, everywhere.

Since book is used interchangeably for content (I wrote a book) and object (hand me the book), it may seem as if physical books are identical with the words they contain. But unlike e-books, which exist solely as disembodied data and now comprise nearly 15 percent of total book sales in the US, physical books carry with them their place of origin, spatially and temporally. The object encompasses both now and the past, all of its previous owners and me. Embodiment is inefficient — only one book per physical book! — but the meaning it encodes is irreducible, invaluable, and inaccessible through any other medium.

I was seeking out this kind of meaning when I bought an early printing of George Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier. The book arrived from England, where it was born nearly a century ago. The concave spine told me someone else had spent time with it open. Written in all caps, at the bottom of the orange cover was: LEFT BOOK CLUB, NOT FOR SALE TO THE PUBLIC. This fellow reader belonged to an ideological organization.

I opened the book. Someone had inserted two pieces of LEFT BOOK CLUB ephemera, printed on cheap, tissue thin paper. One was a membership application, which exhorted current members to sign up their friends: “The aim of the Club is a simple one: it is to help in the terribly urgent struggle for World Peace & a better social and economic order & against Fascism … ”

That worn orange cover had been new in 1938. What became of the reader who made that spine concave? What were they imagining the future held when they read Orwell’s devastatingly honest account of poverty, his withering critique of middle-class socialism?

The other piece of ephemera was a single broadside, folded in half, titled “CHRISTMAS 1938.” The subtitle: “Refugee Baby Frozen to Death.” What follows is a description of 5,000 Jewish refugees at the Polish-German border, suffering like the impoverished British citizens in Orwell’s account, and as I read it, I am there with Orwell and this anonymous club member — My god! It’s Christmas of 1938, and I’m there with them!

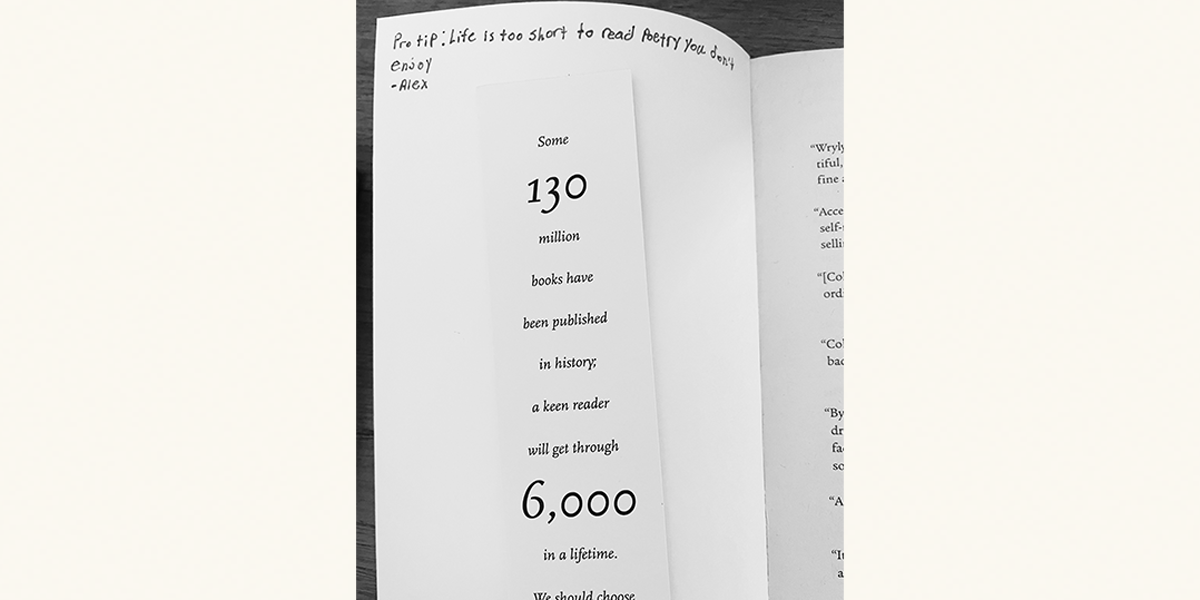

Thankfully, author signatures, old editions, and unique ephemera are entirely unnecessary for book magic. In the crucible of a book, a passing gesture can be alchemically transformed into a powerful spell. Consider Alex, who completely changed my reading habits. I met him/her in the free book bin outside James Madison University’s Rose Library, where someone had left Ballistics, a book of poems by Billy Collins.

I already own and enjoy one Billy Collins book — Picnic, Lightning — so I picked this one up to see if I’d like it as much, or at least more than the person who had given it away. On the top of the inside front cover, written in green ink with a steady hand, was an inscription to no one in particular: “Pro tip: Life is too short to read poetry you don’t enjoy. — Alex”

Here was a mystery! Did Alex give the book to someone who took the advice? That would be amazing, true dedication — giving away a gift, to honor the giver. Or did Alex write the line as a Marie-Kondo-ish ritual of parting, then leave the book. Alex, who are you? Who carries a green pen with them? What wonderful obedience to the inscription!

I kept the book. I enjoy the poems nearly as much as those in Picnic, Lightning. But even more important is the energy of Alex’s spell, which, as I said, changed me completely. No longer do I finish books just to finish them. This accidental incantation freed me to put a book aside with no guilt. Whenever I falter in my resolve, permission pulses out from the spine of that book on my shelf. The spell is stronger now, since I happened to find a bookmark that reflects the same sentiment, placing it alongside Alex’s advice.

Stories like this one, that connect a physical object with its origin, are known by collectors as provenance. If I were to give away my copy of Ballistics, the provenance would be vague: Someone named Alex wrote in it, and perhaps someone different put a bookmark in it.

But book owners can call up distant spirits through research, strengthening the provenance filling it out. If I put my own name in the book — as I did just now, in pencil — a future owner will know it belonged to Alan Levinovitz, an uncommon name which, if googled, allows them to infuse the book with whatever they find out about me.

This essay adds another layer, since, should the next owner happen to find it and read it, they are now co-incident with the very book that inspired these words. Their care and effort constitutes a sacrifice to gods of origins, who lend their blessing to the object. Like me, booksellers revere such blessings, and insist on leaving ephemera in its place, lest meddling weaken or break the spell.

Not to get into a philosophical analysis of magic, but I’d classify all of these as “origin” magic, a category that includes other powerful spells like naming. But unlike naming, provenance magic depends on a key ingredient: honesty. A dark, twisted version substitutes lies, but I wouldn’t recommend it to would-be enchanters. Those lies will haunt you.

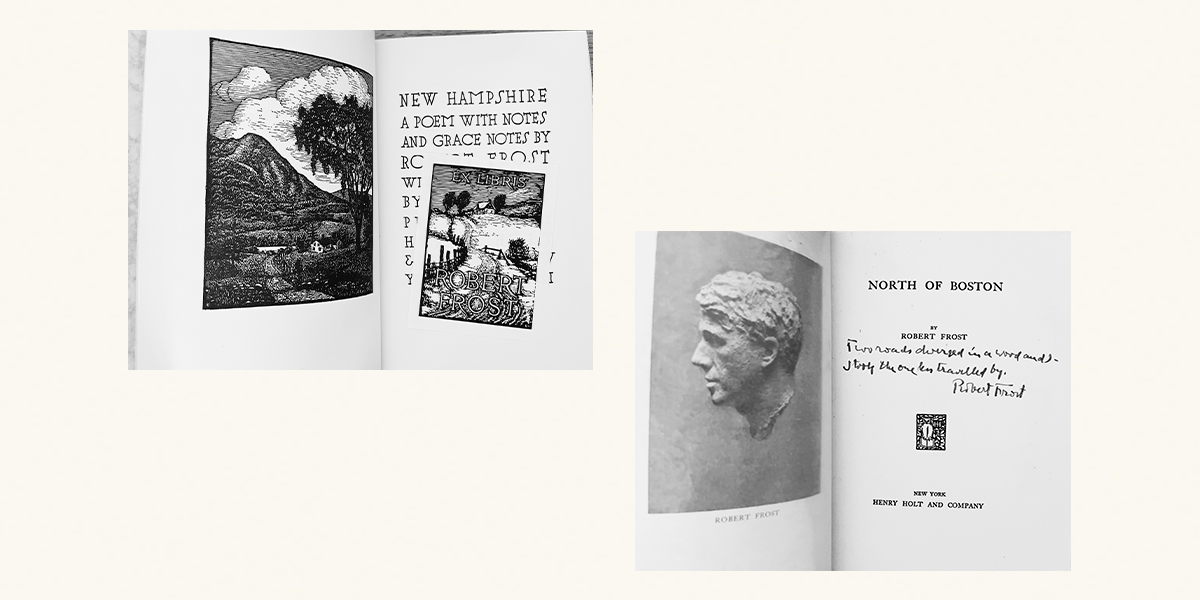

Don’t take my word for it. Arguably the most famous modern English poem — and inarguably the most widely misread English poem — is about the magic of provenance and the importance of being honest. I’m referring to Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” in which he fesses up to the mendacious temptation of inventing an inaccurate origin.

This is — yes, Alex — a poem I enjoy immensely, and which, I believe, justly deserves its fame, even if people are constantly screwing up the message. I teach it to my students, I memorized it, and a line from it happens to grace the most valuable book in my entire collection, a battered later printing of Frost’s North of Boston.

When signing books, Frost was fond of including manuscript lines in his easy flowing hand. On occasion he even wrote out entire poems. But lines from his most famous works are rare, like “Mending Wall” or “Nothing Gold Can Stay.” Among those hits, “The Road Not Taken” is both the greatest and the rarest. I shiver every time I read those blue-inked letters in my battered copy of North of Boston: “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I — / I took the one less traveled by — Robert Frost.”

It's a lie. Not the story I’m telling, but the line itself.

The poem is a confession of that lie. Frost writes that he came to a fork in the road, and was drawn to the road that “wanted wear.” But he immediately revises his assessment, and admits the truth: “Though as for that the passing there / Had worn them really about the same, / And both that morning equally lay / In leaves no step had trodden black.”

Both roads were about the same. But Frost knows that’s a lousy story. He feels, and confesses, the swelling temptation of black origin magic. “I shall be telling this with a sigh / Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— / I took the one less traveled by, / And that has made all the difference.”

This is a poem about making an arbitrary choice, and, in retrospect, wanting it to have been iconoclastic. It’s about the impulse to lie, “ages and ages hence,” regarding what you did. And it’s a hymn, not to iconoclasm, but to truth-telling in the face of temptation.

By confessing to the reader, the poem neuters the lie.

Mercifully, the literal inimitability of his penmanship, combined with the obvious age of the ink, authenticates the lie Frost wrote in my book. But some origins are not so clear. They are dubious or, worse, deliberately faked. As Frost’s poem so deftly explains, the impulse to create meaning through invented origins is strong. In the case of books, even more so, because such lies create financial value.

Consider another jewel of my collection, a well-preserved copy of Frost’s classic, New Hampshire, with woodcuts by the great J.J. Lankes. In addition to being a master of woodcuts, Lankes also designed Robert Frost’s personal bookplate — a paper label also known as an “ex-libris” that’s pasted into the front of a book. Bookplates are key to tracing provenance for collectors who want to own a book that once belonged to a specific person.

Still better, I happened to come across an original, unused, Lankes-designed Frost bookplate, owned by an acquaintance of Frost’s daughter. In keeping with my mania for ephemera magic, I placed this bookplate in my copy of New Hampshire.

Frost and Lankes once sat together, working out the design for this very bookplate. Frost had many printed, but he died before he could use this one, and so the aura grows.

I told my friend and mensch Michael DiRuggiero, of Manhattan Rare Books, about my wonderful find. “Ha!” he said. “Paste it in there and you could say it’s Frost’s personal copy!”

Two roads diverge in a wood … and one increases the value of my book by around $1k.

As part of my side gig as a book dealer, I partner with Michael a lot. Michael is obsessively, puritanically scrupulous about provenance. He would never do anything like what he joked about to me. If he doesn’t have airtight provenance, beyond a reasonable doubt and to a moral certainty, he refuses to include it in his descriptions — even when other slightly less honest booksellers might.

Not everyone in the professional booksellers’ guild is so scrupulous, but membership requires at least some allegiance to the white magic of honest origins. If you’re caught playing fast and loose too often, the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America will kick you out. There’s zero tolerance for the flaming pentagram of forgery that conjures demons instead of history.

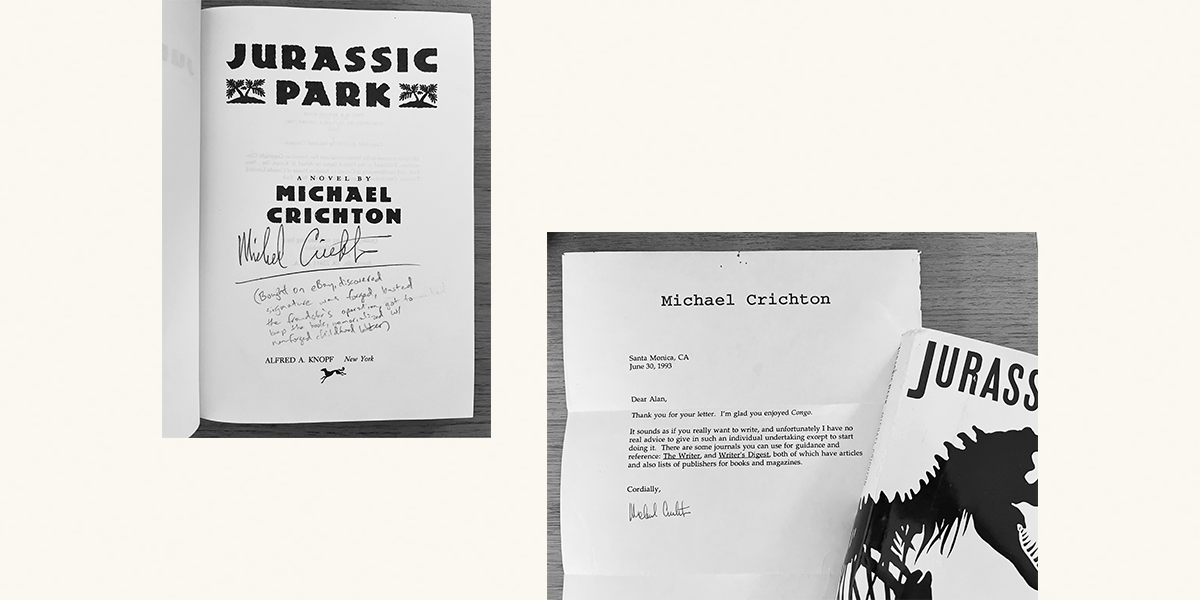

I am, as everyone ought to be, terrified of evil spirits, so I do my part to prevent their presence in my books. One of them showed up in my signed copy of Jurassic Park, purchased on eBay at a remarkably low price. Too low, it turns out: I got a bad vibe when the book arrived, and closely examined the seller’s other items. Most were inscribed by famous authors, and I managed to find a couple inscriptions that had been copied, in form and content, from authentic books available online.

Busted and reported: eBay ended their account, refunded my money, and told me I could keep the Jurassic Park with the forged signature. I knew exactly what to put inside it to banish the demon: a precious letter, on Michael Crichton’s letterhead, written to twelve-year-old me! I’d written to him, asking for advice on becoming a writer. His honest answer: “Start doing it.” The authentic signature on that letter sits next to the fake one, along with a note I made in light pencil telling the story of the book.

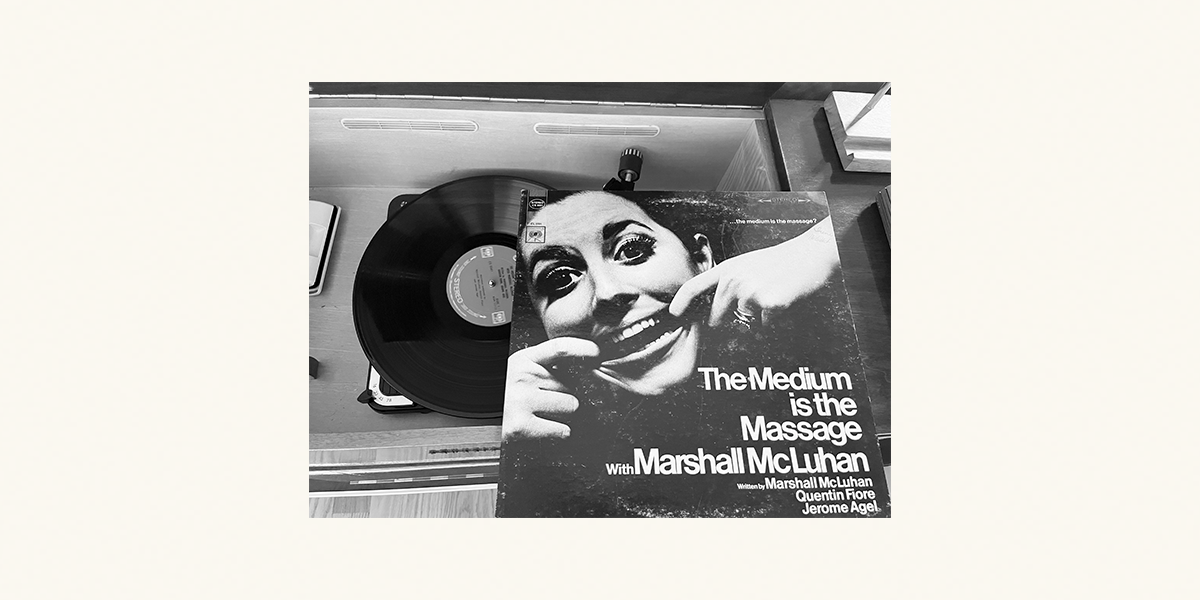

Marshall McLuhan famously declared that “the medium is the message.” I believe enchanted physical books are not just a type of media, they are actual mediums, gateways between the living and the dead, the present and the distant. When I hold that “CHRISTMAS 1938” broadside, I attend a tiny séance.

As an academic, I’m also fastidious about disclosing the provenance of ideas, so I should explain that I didn’t make the connection to this alternate, spiritual definition of medium. I heard it from Andrew McLuhan, grandson of Canadian media theorist Marshal McLuhan. Talking with him was a transformative experience: It transformed me, my copy of Middlemarch, and, if you are reading this in a physical form, it also transformed your magazine into a Maira Kalman-style magic kit.

At first, I wanted to write this essay as a defense of physical books, and an attack on electronic media — diatribe, not an homage, with some studies about the virtues of reading printed material; a laugh at British Roald Dahl enthusiasts whose ebooks of Dahl classics were auto-updated with bowdlerized versions; some sneering at folks who get their Kindles signed.

These new digital mediums had their uses, I thought, but they were ultimately soulless. Scanning my shelves for inspiration I saw Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage, which, like many books I own, I hadn’t yet read.

Far from romanticizing old media, McLuhan embraced the technology of his day. His book was an avant-garde pastiche of fonts, photos, and aphorisms. Who was this guy? I discovered he’d come out with an “audio” version of the book — not an audiobook, but a manic pastiche of music and soundbites, produced by John Simon (who also produced Leonard Cohen’s debut album — a Canada connection!) and released as an album in 1967 by Columbia. Making it relied on cutting edge technology, quite literally: They had to cut, paste, and layer strips of audio-tape to create the experience, which at the time could not be replicated in a different medium. Astonishingly, it sold well. Radio DJs played it regularly. I bought the record and listened to it while working on this essay. The paradox was intense: deliberately cutting edge tech from the past, transformed by time into a nostalgic physical object.

I wanted to know more about McLuhan. Hunting around online I discovered the McLuhan Institute, run by Andrew. Of all the sources I could consult, I thought Andrew’s provenance made him an ideal dialogue partner. We Zoomed, and I learned the Institute was a one-man show. Like a monk tasked to guard relics, Andrew oversees his grandfather’s entire library, working to digitize it, and spread the work of both Marshall and Eric McLuhan (Andrew’s father and Marshall’s son).

Through my screen, Andrew gave me a tour of the place, which seemed to teem with spirits. A copy of Ezra Pound’s ABC of Reading had been heavily annotated by Marshall. His smoking jacket was there too, along with books produced as collaborations between Marshall and Eric, father and grandfather.

The mercenary bookseller part of me had to ask.

“Why don’t you sell any of this? Digitize it and sell the originals?”

After all, Andrew wasn’t rolling in wealth. Neither running the Institute nor writing poetry (he is a poet) yields huge cash flow, and that McLuhan archive was worth tens of thousands of dollars.

Andrew shook his head. “I’ve had people come in, I put something like this in their hand,” he said, holding the Pound close to the computer camera. “And they cry. You’re not going to pull this virtual book off the virtual shelf, and have that emotional experience.”

He went on to make the “medium/spiritual medium” connection, and his reverence for physical books made me think he might be anti-technology. But it immediately became clear he wasn’t. One of Andrew’s primary goals is making the McLuhan archive accessible, and he emphasized how the internet facilitates that in ways the analogue world never could.

After our conversations, Andrew sent me a variety of physical media by mail: a pamphlet written by his father, a photocopy of a short autobiographical essay by Marshall McLuhan, some cool stickers with a pigeon standing on top of a W, and an original poem.

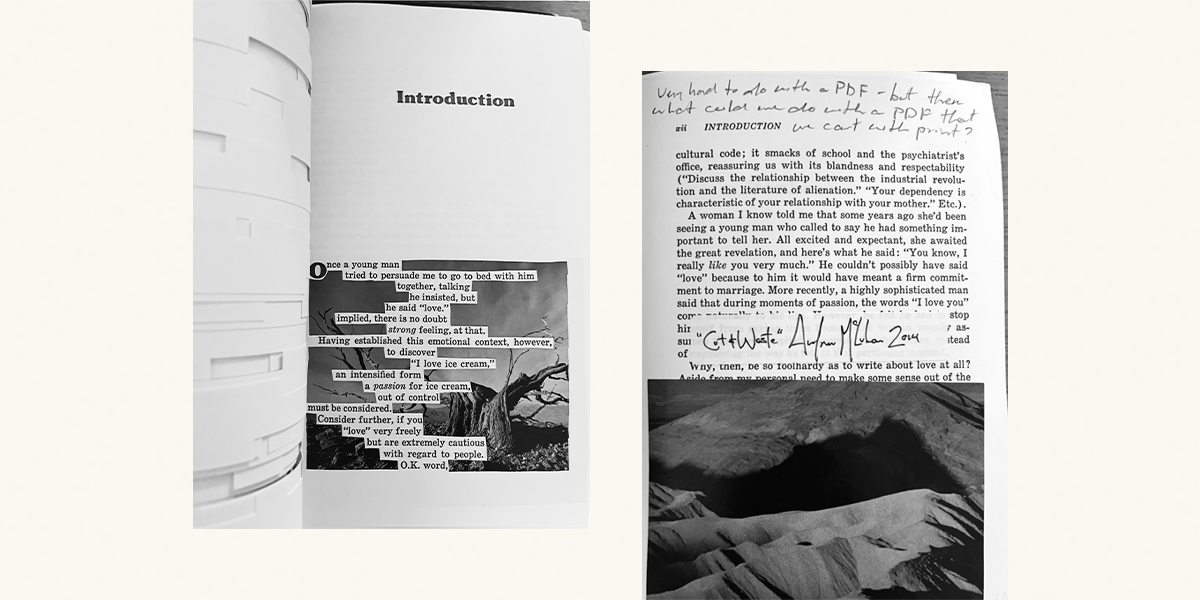

The poem was an exercise in sacralizing physical texts, a call-back to the pastiche technique of the Medium is the Massage record. Andrew began with a full page of text from a random book, then cut away most of the page, excavating a new text, his poem, from the old one. He then pasted it onto a picture.

On the back of the poem, he wrote a note to me in pencil: “Very hard to do with a PDF — but then, what could we do with a PDF that we can’t with print?”

This essay is my answer — my echo, my reformulation — of Andrew’s question. I asked about the mysterious stickers, and Andrew told me that, actually, they go the other way. The pigeon is upside down, clinging like a bat to an M. He also told me the provenance of the image, the origin of the iconography (which is hilarious), but I’ll leave that for people to discover themselves.

Anyways: If you are reading this essay online, you can see a picture of the sticker, oriented properly on the kaleidoscopic endpaper of my Middlemarch. In fact, you can see photographs of every object I mention — even a screenshot of Andrew himself, holding up the Ezra Pound to me! Those reading in print only get to see a few of these images.

But in the print magazine, you’ll find your own sticker.

I’ll channel that master enchanter, Maira Kalman: You could stick it onto a laptop or a water bottle, or you could stick it inside of a book. If you choose the latter, it may be discovered at some point in the future, when someone browses through, and they become part of an ancient, endless spell.

Or you can leave on the adhesive backing, in which case they’ll be a thing that falls out of a book.