“That was a book from the 1980s — crudely printed, roughly translated by today's standards — but I was absolutely electrified. I stayed awake for days and nights in university reading it, dreaming even then of building a world-class company.”

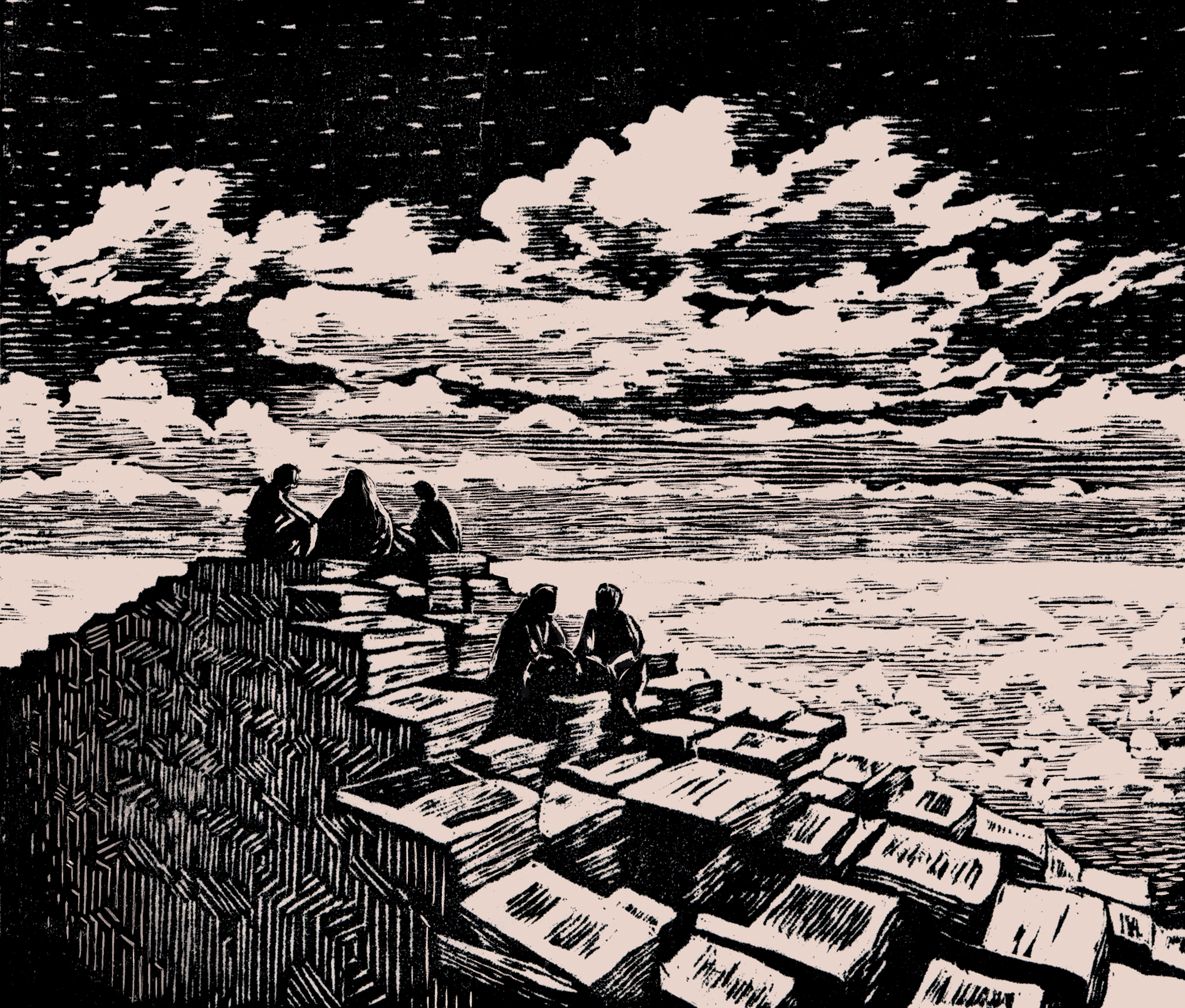

In 1987, Lei Jun 雷军 was a 21-year-old student in Wuhan University’s computer science program. The book that had set his imagination alight was Fire in the Valley 硅谷之火, which chronicles the evolution of 1970s homebrew hacker culture into global titans like Apple, Microsoft, and IBM. The heroes of that story, of course, were visionaries like Steve Jobs. Lei Jun’s trajectory — he founded Joyo.com (later acquired by Amazon), built Xiaomi into a smartphone colossus, then wagered billions on electric vehicles — would unfold directly from that initial act of reading. His nickname became “L-obs,” a portmanteau fusing “Lei Jun” with “Jobs.”

Last August, the writer Tanner Greer published an influential post on the “Silicon Valley canon.” Tech luminaries like Patrick Collison and Nils Gilman followed up with their own contributions. Lei Jun’s story compels me to ask: What is the Chinese tech canon? What intellectual works fuel Chinese entrepreneurs’ ambitions, running continuously in their cognitive background?

And does a unified “Chinese tech canon” even exist? China’s tech elite spans wider generational and ideological gaps than its Silicon Valley counterpart. A founder who came of age in the 1970s during the heyday of Maoism has a fundamentally different outlook on the world from a 2020s AI entrepreneur who graduated from Stanford and decided to go back to Shanghai. Unlike Silicon Valley’s relatively cohesive aristocratic class identity where everyone shares certain intellectual touchstones — Chinese tech founders remain fragmented by generation and relationship to state power.

Still, there are some things they have in common. Some Chinese tech founders see themselves as Silicon Valley’s progeny. They code, they build, they disrupt, they invent, they conquer — to borrow Greer’s words. Yet they inevitably remain embedded within China’s distinctive historical trajectory, its institutional framework, and its market dynamics.

More recently, China’s unstoppable technological ascent has forced elites in Silicon Valley and Washington to question their assumptions about American exceptionalism. Silicon Valley has been consumed by China curiosity, and in some cases even envy. Yet the communication flows asymmetrically. Silicon Valley, along with its Western knowledge apparatus, has long served as the center of systematic intellectual production, exporting ideas unidirectionally with overwhelming force. By contrast, Chinese tech methodologies, frameworks, and even memes have not been transmitted to the West with equivalent scale or depth.

“We are the progeny of the Valley”

As the host of the popular tech podcast Bg2 observed: “Every founder and VC in China studies the West to a nauseating degree. They listen to all the podcasts, read everything, study every talk, and comb the financials. The West doesn’t do that for China.”

At times, the attention can look like ritualistic devotion to Silicon Valley texts. After Lei Jun discovered Jobs’s story in Fire in the Valley, he devoured the wave of management classics circulating in translation — Jim Collins’s Built to Last, Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm, Eric Ries’s The Lean Startup. Lei embedded their lessons directly into Xiaomi’s innovation DNA: rapid prototyping, obsessive user focus, blitzscaling to capture markets.

Wang Xing 王兴, founder of Meituan, one of China’s super apps, became famous as China’s philosopher-founder. A compulsive blogger during his days on Fanfou (China’s Twitter clone), Wang posted more prolifically than Elon Musk does now. His archived thoughts — over 150,000 posts rescued by devoted fans — wandered from Qing dynasty history to Montesquieu.

Most of all, their thinking shows the influence of Peter Thiel. Wang frequently cites Thiel’s concepts in both public speeches and internal discussions, and regularly recommends Zero to One, Thiel’s 2014 bestseller. He even frequently poses Thiel’s signature question: “What important truth do very few people agree with you on?” Thiel argues successful companies should pursue “monopoly profits,” escaping endless price competition to focus on innovation and long-term value creation. Meituan exemplifies this theory applied to Chinese internet markets — achieving dominance through patient market-building rather than direct confrontation.

The pattern extends across generations. When Tencent CEO Pony Ma 马化腾 wrote the foreword for the 2011 Chinese edition of Clay Shirky’s Cognitive Surplus, a book arguing that the internet helps individuals use their free time to create instead of just consume, he described the regular user’s cognitive surplus as “one of the greatest dividends the internet age has bestowed upon internet practitioners.” In the years following, Tencent’s products — the superapps dominating content, video, and communication, alongside their gaming empire — evolved toward increasingly open platforms that encourage user-generated content and sharing. Baidu’s founder Robin Li’s 李彦宏 regular reading encompasses Ben Horowitz’s The Hard Thing About Hard Things, Ray Dalio’s Principles, and multiple Malcolm Gladwell works. Reflecting on Horowitz’s memoir, Li said: “Reading it feels like reliving my own experiences.” This intimate identification with Silicon Valley narratives reveals how deeply American entrepreneurial mythology has penetrated Chinese tech consciousness.

Today’s new generation of AI founders also expressed their devotion to the Silicon Valley canon. Moonshot AI’s Yang Zhilin 杨植麟 cites David Deutsch’s The Beginning of Infinity as formative for his thinking on large language models. Horizon Robotics’ Yu Kai 余凯 channels Thiel verbatim: “What's the secret others don't see? Where's the bug in the world?” Li Auto’s Li Xiang 李想 distributes the “Steve Jobs Trilogy” alongside The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

China’s publishing industry has pursued translation with extraordinary aggression. When Ashlee Vance’s Elon Musk biography appeared as Iron Man of Silicon Valley in the summer of 2016, I was home from California for break. Beijing’s subway line four was plastered with Musk’s crossed-arm pose — a futuristic strongman image. How many young Chinese engineers read that story and plunged into EVs, creating today’s dominance? The three founders of China’s EV triumvirate “NIO-XPENG-Li Auto” — all cite the biography as an important influence. The cult runs so deep that Musk’s mother Maye became a Xiaohongshu influencer after her memoir topped Chinese bestseller lists.

Wired founder Kevin Kelly commands even stranger devotion. The Valley’s tech oracle discovered his quasi-Daoist cosmology resonating with Chinese appetite for grand frameworks. His vision of technology as an autonomous force merged seamlessly with state rhetoric about “indigenous innovation.” The creator of WeChat, Zhang Xiaolong 张小龙, made Kelly required reading at Tencent, publicly endorsing his books Out of Control and What Technology Wants. Within the WeChat team, product managers carried copies of Out of Control like scripture; Zhang had declared that any product manager who hadn’t read it possessed an incomplete knowledge structure. Unlike his niche American influence, Kelly became a cultural phenomenon in China — traveling constantly, lecturing at universities and corporations. His latest book, 2049: The Possibilities of the Next 10,000 Days, was co-authored with Chinese collaborator Wu Chen, using 2049 — the People's Republic’s centennial — as the title. Written for and published within China, no English version has been announced. I read the book and found it genuinely endearing. Kelly stands as a rare figure in Silicon Valley — an influential voice whose authentic intellectual curiosity translates into optimistic analysis, refreshingly free from the prejudice and defensive alienation that mars most Western discourse on China’s technological rise.

The publishing ritual that most intrigues me is perhaps best exemplified by the Chinese edition of James Gleick’s The Information, a history of the information age published in 2011. When it arrived in Chinese, the book carried multiple forewords: Lei Jun, Zhang Xiaolong, Wu Jun (a well-known tech writer who translated Fire in the Valley), and even a philosopher from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Four or five prefaces sometimes crowd a single book — each entrepreneur competing to demonstrate proximity to Silicon Valley’s intellectual currents.

This multiplication of endorsements is uniquely Chinese. Each preface transforms the book into a symposium, with founders vying to show they belong to the same conversation as Jobs and Musk. The subtext reads: “I too participate in the lineage of global innovation.” Their hunger for legitimacy betrays persistent anxiety — Chinese entrepreneurs refuse to remain passive recipients of Silicon Valley wisdom; they demand recognition as active contributors to the same intellectual project.

The red canon and grey canon

When I dug into books about Ren Zhengfei 任正非, the founder of Huawei, I was obsessed with his frequent use of Maoist vocabulary. At eighty years old, Ren belongs to the same generation as Xi Jinping, shaped by the psychological architecture of the Mao era. This generation appears to be tougher and more patriotic than their younger counterparts. But “reading Mao, using Mao” extends far beyond Ren’s cohort. I discovered that many companies operating in China’s gladiatorial markets — those requiring deep penetration, mass mobilization, territorial expansion, and maintenance of “iron armies” (华为铁军) of salespeople — turn to The Selected Works of Mao Zedong. Wang Xing, the Meituan CEO, captured this phenomenon precisely: “After several years of entrepreneurship, I increasingly admire the Communists before 1949. Politics aside, I find it simply incredible that they could survive and grow stronger under such harsh conditions.”

Within the operational context between founders and middle management, The Selected Works of Mao Zedong circulates more like a tactical manual than political doctrine. On Protracted War’s strategy of “encircling cities from the countryside” translates directly into capturing third and fourth-tier markets before ascending to first-tier cities — the essential playbook behind the rise of PDD (the parent company of Temu). “Serve the People” ( 为人民服务) becomes “Customer First” for consumer applications; “self-reliance” merges seamlessly with “avoiding technological bottlenecks” — vocabulary drawn directly from Mao’s conceptual universe.

Needless to say, Mao’s transformation of China penetrated the cultural marrow. For many founders, Maoist texts serve practical purposes. This “red canon” provides blueprints for grassroots organizational mobilization: how to rapidly recruit, train, motivate, and retain thousands of front-line workers — delivery personnel, merchants, customer service representatives — in environments characterized by information opacity, brutal competition, and shifting regulatory boundaries. It offers a shared public language that compresses communication costs while maintaining morale and directional clarity.

The red canon and Silicon Valley canon never contradict — they coexist seamlessly within the same enterprise. Huawei, as one of the world’s most successfully globalized companies, appears intensely patriotic precisely because of this effortless code-switching between intellectual frameworks. Internally, Huawei has nearly replicated IBM's Integrated Product Development process wholesale, adopting thoroughly Western management practices. Yet from the outside, you would never detect the company’s profound absorption of Silicon Valley orthodoxy. This dual fluency — speaking the language of revolutionary struggle for internal mobilization while implementing McKinsey-grade operational excellence — represents a uniquely Chinese form of corporate bilingualism. The company’s public patriotism masks its private cosmopolitanism.

Simultaneously, there exists what I call the “grey canon” — a collection of texts that are opaque, ancient, yet foundational. The corpus of classical Chinese texts rarely appear on glossy startup booklists, yet they silently scaffold how entrepreneurs think about power, time, and their place in the world.

Confucius’s Analects 论语 and Laozi's Dao De Jing 道德经, along with centuries of commentary, remain the grammar of Chinese organization and authority. To read them is to access the operating system that still governs how hierarchies are constructed, how authority gains legitimacy, and how individuals negotiate between duty and innovation. Han Feizi's 韩非子 Legalist doctrines resurface in boardrooms when founders speak of “iron armies” of sales staff, or when delivery companies design ruthless incentive systems calibrated with Legalist precision between reward and punishment. The Confucian-Legalist synthesis constitutes China’s “deep infrastructure” no less than its electrical grid or high-speed rail network: invisible to casual observers, yet indispensable for making complex systems cohere.

To describe Chinese philosophy as a footnote to Confucius is deliberately provocative, yet not entirely misleading. Just as Western political institutions remain haunted by Plato and Aristotle, China’s bureaucratic and corporate life still moves within Confucian orbits — mediated by Daoist flexibility and Legalist severity.

For me, approaching these texts as an adult—after years of resisting Confucian orthodoxy in school — proved revelatory. They explained more about the enduring value gaps between China and the West than any management manual or policy paper. When Arthur Kroeber describes China as a “deep and turbulent ocean” where ancient currents persist beneath contemporary surfaces, he gestures toward this submerged canon. Without it, the Chinese tech scene looks like an erratic product of capital frenzy and policy chaos. With it, apparent disorder resolves into patterned continuity spanning two millennia of statecraft and survival.

Policy texts also receive scrutiny equivalent to scripture. Just to name a few: The National Medium- and Long-Term Program for Science and Technology Development (2006–2020), the Made in China 2025 plan, Xinhua and People’s Daily “commentator articles” are sometimes parsed line by line, with slogans like “new quality productive forces” migrating overnight into company slogans.

Finally, there exists the reform-era and contemporary canon. Ezra Vogel’s Deng Xiaoping and Deng Xiaoping’s Selected Works contribute mantras such as “development is the hard truth” and “crossing the river by feeling the stones.” Xi Jinping’s On the Governance of China is quoted selectively by corporate spokespeople seeking alignment with Party narratives and political loyalty.

Jin Yong and Liu Cixin: the Tolkien and Asimov for China’s Tech

“Every man must read Jin Yong,” according to Jack Ma. Yong’s sprawling martial-arts saga offered a distinctly Chinese romantic cosmos — the jianghu, a world of outcast martial artists which is at once archaic and modern, saturated with obligations, betrayals, quests for transcendence, and the stubborn pull of human sentiment. Across fifteen novels, over a thousand characters, and nearly ten million words, he provided millions of Chinese readers with their first encounter with a hero’s journey, idealism, and the bittersweet compromises between loyalty and ambition. If Silicon Valley’s celebration of reading has blended uncomfortably with the worship of power — as political scientist Henry Farrell argued in his response to Greer’s essay — then China’s tech canon reveals a more complex entanglement: reading intertwined with fear and reverence of state authority, the perpetual tension between individualism and collectivism, and the ancient Confucian dilemma of chushi 出世 (withdrawing from the world) versus rushi 入世 (engaging with worldly affairs). Jin Yong’s work is a moral laboratory for modern Chinese identity — teaching readers how to navigate power without fixed rules, how to build reputation in opaque hierarchies, and how individual mastery coexists with collective belonging.

Just as tech founders mined Tolkien’s legendarium for names like “Palantír” and “Andúril,” Alibaba embedded Jin Yong into its corporate DNA. Employees took on “huaming” (literary sobriquets) from Jin Yong’s characters; meeting rooms became “Guangmingding” (Bright Summit) or “Peach Blossom Island”; Ma’s own office was named after a reclusive martial-arts utopia. Even the company’s value systems were couched in martial-arts metaphors such as the “Nine Swords of Dugu” or the “Six Veins Divine Sword.” To be inside Alibaba was to symbolically inhabit a Jin novel. In fact, this is more broadly true of the early Chinese internet. The first generation of Chinese internet users, my own father among them, often chose their online IDs from Jin’s novels. This was not mere nostalgia but a way of extending the jianghu into digital life. In my childhood memory, my father’s screen name came from Flying Fox of the Snowy Mountain, typed out with the era’s quintessential skill: mastering the Wubi input system.

More recently, Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem has become for China what Asimov’s Foundation was for the United States: a literary scaffolding for thinking about technology, geopolitics, and the fate of civilizations. As Fudan University professor Yan Feng observed, Liu “single-handedly elevated Chinese science fiction to the world stage.” His novels minted phrases that have since entered China’s everyday political and business lexicon: jiangwei daji (dimensional reduction strike), mianbizhe (wallfacer), pobiren (wallbreaker), the “dark forest law,” the “chain of suspicion,” and the “technological explosion.” These terms are now common shorthand in boardrooms and policy circles, invoked to describe competitive landscapes, strategy under uncertainty, or the fragility of trust in both markets and diplomacy. The tech community has seized upon them with particular enthusiasm. Countless essays have drawn “internet strategies of the Three-Body universe” or even “Three-Body management science,” treating Liu’s cosmic metaphors as diagnostic tools for China’s entrepreneurial reality.

Silicon Valley has always drawn heavily on speculative literature as a kind of literary infrastructure for imagination and naming. Elon Musk’s ambitions are inseparable from Robert Heinlein’s interplanetary visions. Jeff Bezos invoked Iain M. Banks’s Culture novels in his dreams of post-scarcity space habitats. Peter Thiel filled his companies with references from The Lord of the Rings — Palantir itself, but also Valar Ventures and Mithril Capital. Even the libertarian edge of Silicon Valley borrows its metaphors from science fiction: Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash and Cryptonomicon have been required reading in certain circles, shaping not only the early culture of cryptocurrency but also the techno-libertarian conviction that code could constitute a parallel sovereign order.

Tolkien, Asimov, Heinlein, and Stephenson provided entire vocabularies and ontologies that Silicon Valley internalized. They offered shared myths of rebellion against bureaucratic stagnation, of a frontier that remained technologically open even if geopolitically closed, of engineers as wizards and coders as world-builders. In Palo Alto cafés, it is not unusual to hear founders quote Asimov’s Foundation when describing their startups, or to frame their ambitions as “building the bridge to the Expanse.” These works are not simply entertainment but tools for communicating a shared ethos.

The Chinese entrepreneurs grew up seeing the jianghu as a model for navigating opaque power structures, forging alliances, and cultivating individual mastery in a world without fixed rules. To read Jin Yong was to learn that survival depended as much on soft power — guanxi, renqing — as on hard power. And in Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem, they encountered metaphors of cosmic precariousness that resonated with their own competitive landscape. Together, Jin Yong and Liu Cixin gave Chinese technologists an imaginative toolkit as rich as Tolkien and Asimov had given Silicon Valley: one rooted in jianghu ethics and cosmic existentialism, the other in systems of magic and spacefaring empires.

Where Silicon Valley imagines itself through Middle-earth, Mars, and cyberspace, China’s tech world thinks simultaneously in terms of the jianghu. Both are literary infrastructures, invisible yet omnipresent. They don’t dictate policy or product, but they shape the imaginative baseline — what a hero looks like, what failure means, how a society might collapse or endure.

Silicon Valley spends enormous energy thinking about China — tracking every policy shift, parsing every regulatory crackdown, jealously looking at every fancy breakthrough. Yet this attention rarely translates into genuine understanding. We’ve become experts at watching China while remaining determinedly ignorant about how Chinese tech founders actually think. The reading list is right there. Chinese tech elites have done their homework — maybe it's time to start your book club.