Jake Eaton: Let’s start off with the story of how PRO — Project Resource Optimization, now hosted at the Center for Global Development — got started, and how you got involved.

Robert Rosenbaum: PRO initially started with a narrow mandate, working with two particular foundations. In the aftermath of the executive order that effectively canceled all foreign aid, those foundations wanted to be able to provide bridge funding to the most important projects that were slated to be cancelled. My co-lead Caitlin Tulloch and I had collaborated with them in the past on using cost-effectiveness as a driving principle for grant-making.

But within the first week of us starting to engage in this work, it became clear that there was a bigger audience. There were likely other like-minded funders out there, who were also interested in providing funding, but lacked the ability to appraise existing USAID funds, and could come to us for a couple of different reasons.

One was the ability to look critically at USAID awards, which are written in a very specific language and format. Most of the groups that we've talked to aren’t used to funding large NGOs. They tend to fund smaller, bespoke projects. These projects might be interesting add-ons to some of the work that was already happening, but to make sense of bigger programs they needed help.

Another way we could be helpful is that those funders were also struggling to make sense of everything that was happening to foreign aid — and that still remains a big question mark in many ways. We had the capacity to learn more about what was likely going to be turned back on versus what was definitely terminated in the long term, across sectors.

So that's how we got started: to build a platform of highly effective projects which needed funding, and that could inform a much broader set of funders.

J: When the cuts first started, I remember wondering whether or not there would be a greater increase of funders interested in pursuing more cost-effective projects, perhaps where they otherwise might not, given that resources are even more finite now. Did you find this to be the case?

R: I think most funders do care about cost-effectiveness, it's just a matter of what version of that definition you're using. But most of the funders that we're talking to were already speaking that sort of language, and it's more a matter of directing them to look at a space they might not already be looking.

I think if all that we're doing is shifting funding decisions in a zero-sum way for institutional donors, our analysis is strong enough that there is a marginal benefit in terms of lives saved. But our goal is also to crowd in more money into this space. We’re starting to see more of, for example, high net worth individuals, who maybe were thinking about philanthropy in a longer-term perspective, wanting to give more now. I'm hoping that continues to grow.

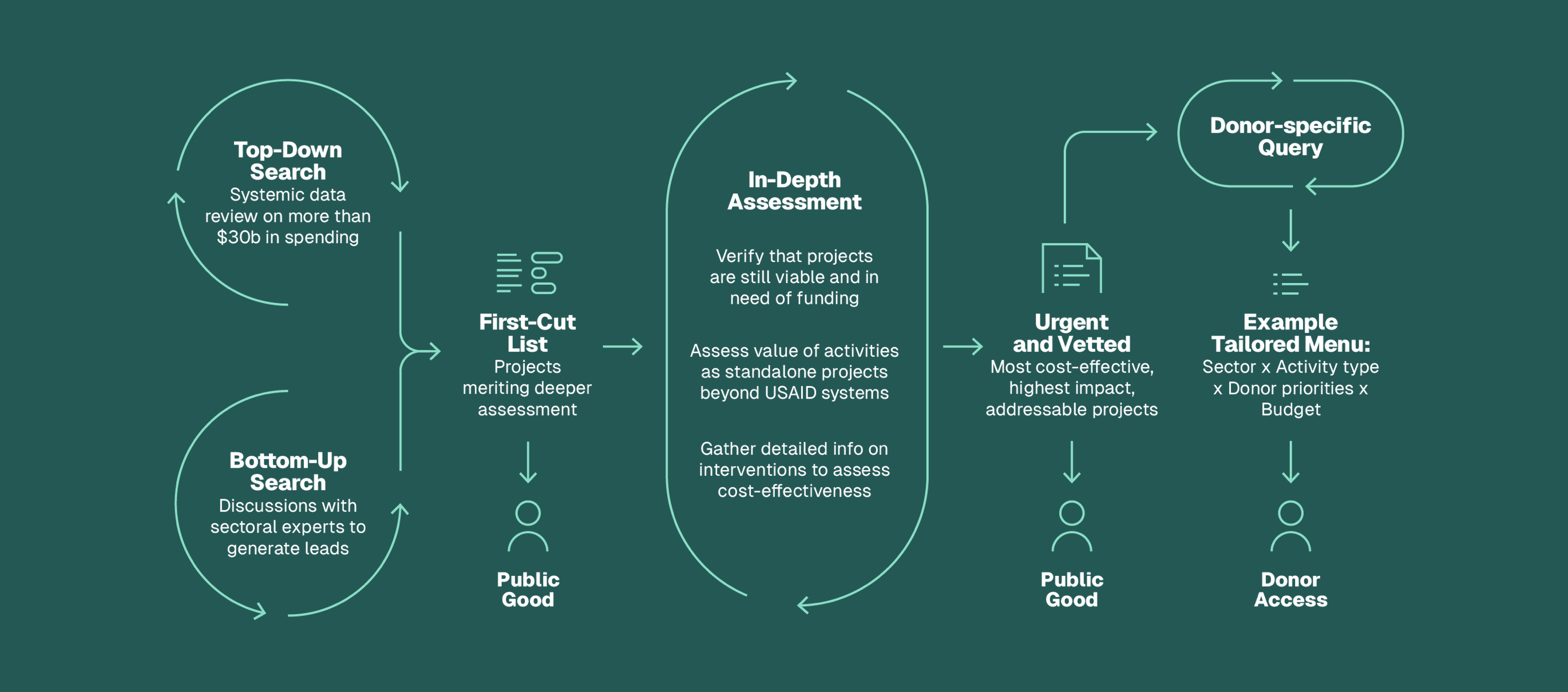

J: Walk me through your process. On a high-level, it started with a big top-down search to see what grants were out there. And then there was a second part of the search that involved going to your networks, identifying projects, and doing your own analysis on each project in terms of cost-effectiveness and efficiency. You had to do it very quickly, too. You’re running fast analytical triage on a large data set. I'm curious how you approach that challenge, how you figured out the methodology, and anything that emerged out of that?

R: I think triage is very much the right word to use here. We have always valued and privileged expediency, while also recognizing the bar of rigor that we were going to need to hit to be compelling and to feel confident in what we were standing behind. The way that we've decided to manage that tension is through as much transparency as we can possibly give, both to funders and to the implementing partners on the other side.

I don't think that we would claim — and we don't want to claim — that we have a complete set of cost-effective projects that can save lives. But I think we can say, confidently, that everything on our list meets that bar.

So in terms of understanding that funnel: We started by looking at all obligations from Fiscal Year 24 from the foreignassistance.gov public database. We then filtered that down using a series of criteria to identify the locations where we think the biggest impact can happen (such as the lowest-income countries), and where the biggest loss will happen. We then filtered to the types of interventions that we know to be cost-effective, to the technical areas that matter most, and excluded the types of awards that we know wouldn't make that list — so administrative support and supply chain, things like that.

From the 600-something projects that met those criteria, what we called our first-cut list, we narrowed down to our urgent and vetted list. There's a lot that happens in between those lists, primarily because the data set we're starting with from foreignassistance.gov has a lot of gaps and is not very descriptive in what it says. It enables us to filter, but only down to "this is probably a good starting point to have conversations."

What we did from there was some very aggressive triaging. We grouped projects by implementing partner, and then reached out to those partners and said, here's what we're trying to do. At that point, we had no idea whether we'd get any traction. A big question was how much we could reasonably ask of implementers when they are short staffed and there's opportunity cost to their time. But we needed enough information to be able to conduct our own assessments to feel confident about our recommendations to donors.

So we created an intake form with a series of questions. The most important was what specific interventions the organization is delivering. We had a checklist for things that we already knew had a really strong evidence base behind them. We also asked how many people it expected to reach, in what region, and for what dollar figure. There are some other questions to understand the landscape, but the real crux of it was the information that we felt we needed to be able to do a rough back-of-the-envelope assessment of the cost-effectiveness and the efficiency of the program.

From there we had a few back and forths with the programs, sometimes asking them, "Hey, you listed these types of interventions or programs that I'm sure are really important but don't meet our threshold," or "This is a $10 million ask. We know no one's going to put forward $10 million, or at least from our experience, we don't think that's going to happen." We tried to get it down into a reasonable proposal for the niche of funders that we're trying to reach. So the information we actually used was not in the original data set. We had to recreate that and get inputs from the implementers.

J: In looking at the cost-effectiveness and cost efficiency, you're relying on previously published data, so for example the Johns Hopkins lives saved tool.. Were your estimates as detailed as knowing the number of lives saved per dollar? Or were you aiming for a broad group of projects that are not only cost-effective but also feasible to replace with private funding. So for example, a $10 million project that’s highly cost-effective might nevertheless be difficult to find funding for. So you had to take into account both what the project is doing and its size. I'm curious how you go about making that as rigorous as possible.

R: The Johns Hopkins list is the basis from which we built our criteria. And we've added a couple other program types over time where we've been presented with really compelling evidence. We decided to include the graduation model for reducing extreme poverty because it has such robust evidence, and while that is not life-saving in the same way that ARVs are, it leads to very positive outcomes in the long term.

As to the right sizing of the award, or the co-creation of what the final product was going to look like, it was a little bit of a combination of both of those. For all the projects submitted, we also received a narrative of the award and of what was being delivered. There were cases where the award might have included some additional wraparound social protection type work, or education linkages — things like that. These are very important, but unless there was a clear cost-efficiency case that could be made to include them, we worked with implementers to refine the award to what we thought a given group would be interested in funding. And our final list is the most targeted version of that.

J: So some of the projects were modified from the scope originally awarded by USAID, in order to make the project more feasible, given current conditions.

R: Absolutely. And I don't want to suggest that we're requiring just singular vertical service delivery because we're not. I think that's oftentimes a criticism, sometimes fair and sometimes not, of this type of cost-effective giving and award making. There are a lot of places, particularly in the humanitarian sector, where there are multiple services that are being delivered and they operate on economies of scale, from malnutrition treatment to healthcare delivery. But each of those things needs to be an intervention that we know is delivering or leading to proven outcomes.

J: It's a ton of work. I'm extremely impressed at how quickly you all moved, so kudos. I know one of the challenges, especially when you were doing the first cut, was simply to figure out what was being cut. It's been incredibly challenging for anyone to get a clear idea of what projects or contracts are being reinstated, whether or not waivers are coming through, whether or not money is being turned back on. In mid-March, you estimated that between 30 and 50% of the most cost-effective programs at USAID had still been cut. I know you've only got a qualitative and narrow lens on this, but if you had to estimate, is that where we currently stand?

R: When we started, we had the horrible advantage — however you want to phrase it — of having to assume that everything was going to be terminated. Then came waivers, but we knew from our experience, and from conversations with other folks, that that waiver process was only in word and on paper. The administration wasn’t doing what we were doing — an actual assessment of awards on the basis of life-saving and cost-effectiveness — in determining waivers.

J: Despite the administration saying, and I’m paraphrasing, that that is precisely what they were doing.

R: Yeah, exactly. I think a side story that could be told from our work — and I'm not going to claim that it's perfect by any means — but I don’t buy the argument that it's not possible to do this type of work quickly and efficiently because the data sets are too complicated. We’ve been doing just that — a very rapid triage and assessment. So even if you're beginning from the starting point that all that USAID should be doing are these core life-saving things — and again, I don't share that opinion — there are ways to have done this much more methodically and rationally than I think happened.

So we started with the entirety of FY24 obligations under the assumption that nothing was going to come back on. But then we’d be told, in conversations with organizations, "Actually, don't prioritize this one, because we just heard that it's received a waiver or it's getting funding. But this one is really our priority. For whatever reason, they're not committing funding to this.”

And so anecdotally, we have good examples of things that should have received waivers that haven't. But we only have a narrow vantage, because our understanding of the overall picture is only at this one specific level. I don't think I can give you a better assessment of the percent. You're not the first person to ask this question, and it's just really hard to track down.

J: How long can most programs float before they need to be entirely shut down or turned off? I know it will of course vary widely based on program and context, but what are the actual dynamics that influence how long a project or program can float, before people take other jobs, or the infrastructure is gone, etc.?

R: In general, particularly in the space of USAID and US government-funded programming, there was intentionally very little leeway or float capacity for these organizations, in part because of the way that financial reporting and financial management was required. There was such an emphasis on preventing waste, fraud and abuse, that it created the type of accounting infrastructure and reporting where there wasn't a lot of runway for any of these projects.

J: I think that is something that goes really underappreciated in some of the criticism I see. I previously worked as a consultant on USAID projects. I remember being in USAID offices where every single file cabinet, desk, chair was labeled "property of USAID" and tracked with a number. We logged every hour we worked and what we did. There’s a behemoth of an accounting system.

R: Yeah, absolutely. To the point where you might say USAID spent considerably more money to avoid fraud than they lost from it. What's really frustrating for a lot of people in this space who have long championed and believed in the need for reform within foreign aid, is that it’s this point that has been weaponized in bad faith by the people who have torn apart USAID, in making claims about things like waste, fraud and abuse that are just factually incorrect.

At Development Innovation Ventures, where I previously worked, all of our awards that we made were what are called fixed amount awards. So they're deliverable-based awards, which is some version of pay for performance. That reduces the amount of HR and overhead that's required to manage those awards, because they don't have to account for every single penny. That was the reason that DIV was able to work with much smaller organizations, not with the traditional USAID contractors, because they could focus specifically on performance.

If anything, I would say that the system had completely overcorrected in the other direction from that. And there are lots of consequences of that, one of which, at least now, is that there is a lot less runway than you would want for a program doing such important work in really high-need areas.

That said, when we first started, our assumption was that the runway was a matter of weeks or months, because that's what we were hearing. It has turned out that in some cases that has not been true. In some cases it has. Offices have shut down, people have gone. There's been tons of layoffs. But some organizations that are not entirely reliant on USAID funding have been able to smooth things in ways that we didn't anticipate at the beginning.

But another reason that the freeze was so devastating is that a lot of these programs are built in arrears. They were already in the red before this started. They built their programs around going red, black, red, black. So there was no cushion to push beyond that.

While the waivers have been mixed, a lot of these programs have been able to receive funding for previous work done. And so that has enabled some of the lights to stay on a bit longer, but there's no doubt — and there should be no mixed messages here — there are fiscal cliffs that have either already been reached or are fast approaching in some of the most high-need areas of the world, where USAID was the provider of life-saving aid that has either disappeared or is about to. And it's pretty tragic.

J: You also prioritized projects that were generating some form of evidence. I'm curious if you can talk about that consideration more, because I think that's an interesting one and deserves some explaining.

R: Yeah, absolutely. So PRO was actually originally called the Lifeboat Project. Somebody very wisely decided to change our name. But I think that metaphor still very much stands. The ship is sinking. So literally save as many children as you can on whatever limited lifeboats there are.

That being said, we knew there were a lot of research studies that were underway and that had been terminated. And not just any research, but projects that had the potential to unlock important information about how to deliver programs more efficiently, or to deliver greater impact and greater outcomes per dollar. And there is even more value in these studies given we need to figure out a future version of aid, or even a current version of aid with many fewer resources to go around. We're going to need innovation. We're going to need smarter, better, faster ways of doing this. And so to eliminate the very studies that have the potential to teach us that felt very self-defeating.

I think the other piece of it, building on that, was really a leverage play. In some cases, the baseline and the midline of the studies had already been done. And so you're looking at either complete loss and complete waste of every dollar that had been spent up to that point or a relatively marginal investment to unlock a lot of value on the other side. So it felt compelling to us to say that if you can close out the remaining, let’s say, $200,000 on this $1.5 million study, you're effectively unlocking a million and a half dollars' worth of evidence generation that would otherwise just disappear into the ether.

J: There are some projects that you've highlighted that just can't be replaced by philanthropic funding because they're so large. So, for example, the Famine Early Warning System, FEWS NET. One of the big criticisms of aid work that we’ve seen is that these countries should be doing these things themselves. But some of these projects really need to be done either at the state level or through multilateral organizations. For curious readers and for skeptics, what are these sorts of projects that just can't be replaced by philanthropic funding or by countries themselves? And for what reason?

R: I would start with the pretense that one of my criticisms of foreign aid is that we had baked in some amount of dependency into the work that we were doing. We had gotten local governments off the hook from delivering very core services that citizens — in their social contracts with their governments — should expect to be delivered through their taxpaying dollars. I think that is a valid criticism. There are some things that should be delivered by governments. USAID was starting to pivot towards a localization effort, where more of the work it typically funds would be done by governments. But I think that it was too slow, and the handover into local ownership was not prioritized.

J: This originates, at least in part, to the so-called Journey to Self-Reliance that began in the first Trump Administration?

R: I think that's right.

J: Where Trump one pushed for greater localization through “self-reliance,” but then of course Trump two has obviously turned that on its head.

R: Right. And I think that's what really caught a lot of folks — I would say literally every person inside that building — off guard. People assumed aid would look different than it had the previous four years, of course. We had a data point from the previous Trump administration. But I don't think any type of planning included complete devastation.

There’s important context here. I think some of the reason why foreign aid, particularly from USAID, had not been as good at actually doing the handover to local governments as many would have liked were the restrictions and earmarks on that funding. There was a lot of hesitancy, beginning in Congress, to channel funding towards government partners instead of paying NGOs. I think because there's a lack of trust.

But then for every question that you've received asking why we are funding NGOs to deliver services that governments should, there’s the converse: How do we know we’re not feeding our taxpayers’ dollars into a corrupt government?

To the question of what are certain things that can't be replicated: The big public, cross-national initiatives like FEWS NET that you refer to, or Demographic and Health Surveys, or DHS, are obvious answers to that. Providing humanitarian support in conflict areas is another clear example. You can't use local governments in those situations because they're unstable or untrustworthy.

There are lots of places in between where there is particular value in global coordination, things like procurement of vaccines, and places where the technical expertise from external entities can help local infrastructure and service provision improve, and in some cases actually leapfrog, some of the challenges that exist in developed countries.

I'm sure there are lots of other examples. One other that I might give, and I’m biased because of my previous role, is an innovation fund. That created an opportunity for people to take risks trying new things across different country boundaries. I think that is something that uniquely sits in a seat like USAID.

J: Have you heard anything about DHS? That strikes me as another example of a hugely valuable and load-bearing program. For our readers who aren’t familiar, this is a survey delivered every several years in developing countries that tracks population, demographics, fertility, and a range of health issues, including nutrition, malaria, etc. It’s pivotal for cost-effectiveness estimates, since it’s often the best source for population and health estimates.

R: I don't know actually. Being a large survey, I imagine that it could recapitulate to some extent. I’ve heard FEWS NET is at least operating on a skeleton level, but I have not heard about DHS.

J: You're playing something of a matchmaking role now between projects and philanthropists. Can you say anything about where you've received philanthropic interest? What kind of foundations or individuals have stepped in?

R: There is a concentric circle of funders that are starting to talk to us, but conversations are still early. The people who have moved money already tend to be the folks that were already closer to the Effective Altruist space. In some cases, they've been able to move much faster than I first assumed, given that EAs are kind of notorious for running 8,000 models before they decide to hit go. I've been impressed with the recognition of the urgency there. That's been really great to see. Shout out specifically to Founders Pledge and The Life You Can Save. They've been working strategically and thoughtfully through the space to try to galvanize others into it.

On the private side, we are just now starting to reach audiences beyond those foundations through the NPR piece that ran and an op-ed I wrote. And we’re hoping to reach more folks who are on the periphery of that space, or are otherwise really horrified by what's happened and want to do something and haven't seen the right opportunity yet.

J: Do you have a pitch for people who may be reading this and are within that space? How much time do we have to fund these things? Why should they be funded?

R: If ever there is a time to dig deeper than you were planning to at the beginning of the year, this is a truly exceptional time for the types of programs doing life-saving care for people in really desperate parts of the world.

I would not argue that you should just throw money at anything that was formerly USAID funded. I don't think they're all created equal. We have tried to do our best to create a hit list of what we think are the most valuable and most important things to keep around. And that’s for two reasons.

One is the obvious lives that you can save with your money, right now. And we can help you figure that out, as we’re currently doing for a number of the projects that are on our list.

But it's more than just the lives today. It is really about buying time over the next year for these programs, and the institutions that deliver them, to figure out what this new equilibrium is going to look like, and to still have boots on the ground to continue work that’s already begun. That can mean a lot of different things. It can mean, for example, longer-term funding coming from an institutional funder like the Gates Foundation into the HIV space, to fill the hole left by PEPFAR. It can mean private philanthropy and larger dollars coming in. It can mean government commitment. Or it could mean complete handover of the program to the local government, if that's what it's going to take.

But the difference between pulling out the plug and walking away versus having a year to strategically plan and exit in a coherent way is really the difference between preserving this work and losing all of the investment that we've made, as a country, to these places. So I think there's a real urgency argument. This is a unique time. I know everyone says "unprecedented" and "unique" three times a day these days. But in this particular context, we've never seen anything like this. And this will hopefully help mitigate the harm caused.

The difference between giving now and revisiting at the end of the year could be the difference between there being something to give to versus there just not being a presence at all. To provide, for instance, ready-to-use therapeutic foods to kids with severe acute malnutrition in Yemen — to pick one project. That's what's on the line.

J: And for further context, you’ve had 15 projects that have been funded totaling $12 million, and there's 45 more that have been vetted and $87 million more that could be committed. But those projects range from a couple hundred thousand dollars to the millions. Is that right?

R: That's a good summary. I would add we've got another 12 or so that are under review.

Now we're starting to pivot away from the sourcing function of our very limited bandwidth. I think we all agree that it is important to get as many good things up there as we can, but at the end of the day, if they just sit on a list somewhere and don't get funded, it doesn't help anyone.