It’s always been a personal fascination of mine what words a culture uses — and what words it lacks. Not only is it a good indication of how native speakers tend to think and feel; the creation of new words reflects new thoughts and new emotions that have become common enough to require a shorthand. Nowhere is this happening faster than on the internet. Every year, dozens of new slang terms spread like wildfire in people’s vocabularies. I thought I’d cover some of the terms I find most interesting that are circulating on the Chinese internet right now.

The Japanese term “shachiku” (社畜) literally means “company livestock.” It gained popularity in China almost as soon as it was invented. But lately I’ve seen many around Weibo joking that not even livestock are worked like Chinese university graduates — cattle will literally die if you make them work 996 hours (that is, 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week). For a time, people likened themselves to machines instead. That was until someone found a better term in a 1984 article from the People’s Daily, the CCP’s official newspaper: “human ore.” It refers to the way workers feel they are a resource to be exploited, consumed, and discarded to fuel the engine of progress. At least you have to maintain machinery and give it enough electricity, graduates felt, whereas they’re now treated like unfeeling rocks. Human ore began trending shortly after it was first used in 2023. That is, until it was banned by the CCP.

In fact, work hours (as well as school hours) are so long in China that a new term has been birthed to describe the heroic preparation required to fully enjoy one’s leisure time: “Special Forces Tourism” (特种兵旅游). It describes maximizing your vacation time to do the absolute most, packing as many as a dozen destinations into one day. A sample itinerary looks like this: You take the overnight train into Beijing. Arriving Saturday morning, you visit Tiananmen Square, the Forbidden Palace, the National Museum, Mao Zedong’s Memorial, the famous Wangfujing shopping area, and a dozen more locations all in one day, quickly taking a photo at each to prove you were there. Then you hop on the overnight to Shanghai, where you do the same thing on Sunday, before riding a train overnight back to work, ready for Monday to start. Along the way, you will want to spend the least amount of money possible, which means sleeping in coach rather than opting for a bed on the overnight train, eating the cheapest food possible, or occasionally spending the night in a 24-hour cafe rather than shelling out for a hotel.

But Special Forces Tourists are elite in one sense: they at least have jobs. The people who don’t have made the term “Kong Yiji literature” (孔乙己文学) go viral. Kong Yiji, the titular character in a short story by 20th-century writer Lu Xun, is an educated, upper-class scholar who fails to pass China’s stringent academic examination for official state posts. Unable to make a living, he is nevertheless too proud of his education and his status to settle for a demeaning job. Instead, he takes to stealing. The story rang true for many of today’s college graduates. In China, unemployment rates are higher the more educated you are. “If I hadn’t gone to college, maybe I would’ve been happy to work in a sweatshop,” the thinking goes. “But now that I’ve been educated, I don’t want to take off my scholar robes.” Though it’s sometimes used in a sarcastic way to describe people who keep looking for unrealistically ideal jobs, for the most part Kong Yiji’s name has become shorthand for describing the reality that the only option college grads seem to have is underemployment or unemployment.

But if you’re tired of unemployed uni graduates whining and want to take them down a peg, you might call them “small-town exam takers” (小镇做题家). This term originated after three highly competitive spots at the National Theatre of China — ostensibly landed only after a rigorous examination process — went to a former boy band singer Jackson Yee and, curiously, his roommates. Understandably, an uproar arose after people questioned whether Yee (and his roommates) had to go through the same exam and interview process as the rest of the populace. In response, Yáng Shíyáng, China News Weekly’s editor, wrote, “All you small-town exam takers can go to as many tutoring classes as you want, and complete practice exams as many times as you want, and you’ll still never get a government job that you feel safe with. And yet when you see an already wealthy celebrity take a government job, you still feel like they took your spot.” The term quickly evolved to describe college grads with no connections who have performed well on standardized tests only because of hard work and repetition. It’s there their talent ends.

PUA is also a popular term in China, popular enough that you can type more or less any three letter combinations (CPU, ICU, PPT, KTV) and people will understand what you mean. In America, PUA stands for “pick-up artists,” many of whom have advertised ways to pick up women by breaking down their self-esteem. In China, the term is applied more broadly to anyone belittling your self-image in order to better manipulate you. You can face PUA from your parents, who put you down and exaggerate how hard it was for them to raise you so that you feel too guilty to not take care of them when they’re old. You can be PUAed by your boss, who makes you think you’ll starve if not for this job, so you better work overtime to keep it. Even society itself can be a PUA by telling you nobody wants you after 25, so you better get married and have kids young.

Under pressure from all sides, Chinese people began talking about “internal friction” (内耗) versus “external friction” (外耗). Internal friction is the more common response to keeping negative emotions at bay. You put on a brave face and internalize to avoid causing anyone else suffering. By keeping it in, it just keeps wearing away at you. But rather than torture yourself with internal friction, you can convert it into external friction by acting crazy. Well, the term is “acting crazy” (发疯), but the actual meaning is closer to “letting it go.” If you’re suffering so much, then screw what other people think and just let it out.

For example, if your mom is constantly pushing for you to have kids and it’s causing a strain in your relationship, a person prone to internal friction might constantly look for polite excuses to avoid their mom. Except then, they are under constant stress and anxiety about what excuse to use next time, and whether their mom has noticed something was up. Whereas a person prone to external friction might just demand to their mom’s face step-by-step instructions for how to make a baby in order to make the situation so awkward that their mom never brings it up again.

So the next time relatives start pressuring you about having kids, you can ask them to their face, “But how are babies made? Nobody ever taught me. What do I? Can you draw me a graph? I don’t think I’m getting it. Do you mind demonstrating?”

That’s assuming you don’t use the “pasta concrete” (意面混凝土) defense. It’s a more or less utter nonsense copypasta that goes something like this: “I can’t agree with that viewpoint. I personally believe that pasta has to be mixed with number 42 concrete because the length of the nail means that it’ll directly affect the excavator’s torque, you know? When you smash it in, it’ll create a large amount of protein instantaneously, otherwise known as UFO, which will severely impact economic growth and may even cause the entire Pacific Ocean and its charger to become nuclear contaminated. Not to mention, with this Pythagorean theorem, you can easily deduce that farm-raised Hideki Tojo can easily capture wild trigonometric functions, so whether this cut of the Qin Shi Huang is radioactive or whether there is precipitation in Trump raised to the nth power doesn’t affect the Walmart and Wei’er Kang (a Chinese soft drink brand) meeting in Antarctica at all.” A speech that goes on long enough and contains enough nonsense jargon that it’ll instantly grind all your older family members to a halt. They’ll have no idea what you’re saying, and they won’t want to admit they have no idea what you’re saying, so it’ll end any conversation with dumbfounded nods around the table.

You might already be familiar with the term “lying flat” (躺平), the movement among young people to put in as little effort as possible: There is no point in growing taller if your inevitable fate is to be chopped down by the state. But lying flat is still a luxury. The assumption is that if you’re doing so, you’re still able to put food on the table. Maybe you have a passive source of income. Maybe you saved up a bunch of money when you were young and moved to a cheap, small town. In other words, these days it’s hard to lie flat. And thus “letting it rot” began trending. The term first came up in sports circles to describe a tactic used by some losing NBA teams: to deliberately lose even harder so that they get better picks during the drafts the next year. It describes an unstable life situation in which everything is on fire and you still don’t have the energy to care. “Lying flat” is always leaving work precisely on time, but at least diligently working throughout the day. “Letting it rot” is when the deadline for your project is in two hours and you haven’t even gotten started.

And being able to lie flat (or even just let it rot) is great, unless someone breaks through your defenses and lands a “critical hit” (破防). The term originally comes from video games to describe certain mechanics where you have to target a weakness or perform a special move to break a boss’s defense before you can actually damage them. On the Chinese internet, this term describes an unexpected event, or a quip, that caused a much bigger emotional impact than you would have expected. When you thought you’d put something behind you or you’d gotten over it, or that it doesn’t matter to you at all, something pierces through all your denial and strikes you where it hurts the most. Here are examples that have caused critical hits: videos of Western kids coming home from school while the sun is still up; European office workers not responding to emails for a week because they’re on break; learning that in some countries depression counts as a disability.

Sometimes, it’s official government terms that get hijacked and turned into slang, like the expression “to lead by a mile” (遥遥领先). It was originally used in state propaganda to describe the state of Chinese scientific innovation and infrastructure. Today, people use it for all other metrics by which China leads the world by a mile, like youth unemployment, abandoned construction projects, or low birth rates.

While there’s always a couple of sarcastic comments under official government posts, when there’s a concentrated effort to overcome the censors, it’s usually called an “attack on the tower” (冲塔), a term borrowed from League of Legends. When it comes to major news, like warning people about COVID, or protesting against COVID lockdowns, people plan these attacks like a video game raid. It’s almost always late at night, when the mods are changing shifts. Sometimes a decoy team makes a lot of noise under a different topic to distract the mods, using official government terms to refer to what they’re protesting about so it’s harder for the algorithm to detect, or otherwise hijacking unrelated, trending hashtags.

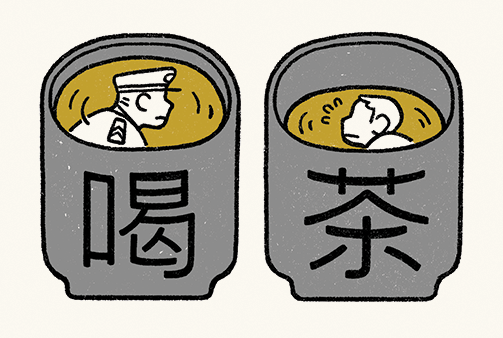

You do have to be careful you’re not invited to “drink tea” (喝茶), though. When people are taken to the police station for anti-government activities, they’re not usually put under proper arrest, because nobody wants a public record of when the arrest happened and why it was made, nor do they want to publicize any evidence. So police will show up and ask you to come to the station for a cup of tea. I think originally this was an excuse used to get people to let down their guard so they didn’t realize they were actually being interrogated. By now, though, everyone knows what it means.

A lot of Chinese internet slang terms take the form of modern-day idioms, four-character words that often condense an entire story. Most of them aren’t too interesting and are just short forms of common sentences. We have 十动然拒, “I’m exceptionally interested, but I have to turn you down.” Or 不明觉厉, “I don’t understand what’s going on, but god if it isn’t awesome.”

But my favourite one to come out of China in the last few years is definitely 鼠头鸭脖, “rat head duck neck.” It came from an incident in Jiangxi, where a student found a rat head in his cafeteria lunch. The school and local authorities both swore up and down that it was just a piece of duck neck, despite photos and videos taken by the student. The event continued to gain attention on the internet until federal authorities investigated and confirmed that it was, in fact, a rat head. A lot of people call the incident the new millennia’s “指鹿为马” (“call a deer a horse”), a story of second-century eunuch and politician Zhao Gao showing off how much power he wielded in government by calling a deer a horse and daring to see if anyone would correct him. Now, the term “rat head duck neck” is used to refer to any official notices or announcements that contain such obvious, outright lies that it’s almost like they’re not even trying.

Perhaps this paints a rather depressing picture of what goes on in China: long work hours with no acknowledgement and upset people with no safe place to vent. While it’s true that the internet is always a magnifier for negative emotions, I think it’d be unfair to dismiss these trends as mere online griping. If I take a look at compilations of trending internet slang from 10 or 15 years ago, it feels like there are more positive terms. Take “逆袭,” “to win as an underdog or unexpected dark horse”. Or “奇葩,” literally “strange flower,” someone who’s odd in a harmless, funny, and maybe even adorable way. I’m not the first person to notice that on mainstream sites like Weibo and Zhihu the tone of discourse seems much more jaded lately.

And, honestly, I think this is great. Self-deprecating terms like “Kong Yiji literature” or “human ore” trending give me hope because giving a name to a social phenomenon is the first step to having discussions about it. Discussion raises awareness and brings people together — and ultimately makes it that much harder for the government to ignore the problem. In China today, I think that’s the only way for change to happen.