Savelugu Hospital is a scattering of block-shaped buildings on baked red earth just north of Tamale, the largest city in northern Ghana. There is a small mosque in the back and a few goats that wander out front. It is one of just over 360 public hospitals serving Ghana’s 33 million people.

At the center of the hospital stands the square outbuilding of the Child Welfare Clinic. In the shade of its padded tin roof, several dozen mothers wait with their children for a monthly health check.

The clinic is busy. Doctors and nurses in the green and white uniforms of the Ghana Health Service scuttle around weighing babies, completing health records, and providing immunizations. While mothers wait, health care workers typically give a health information talk.

We visited Savelugu Hospital in September 2023 while running Maternal Health Initiative, a global health charity we founded the year prior to increase access to family planning in the postpartum period. Our program targeted health information talks like these, adding to them evidence-based family planning information to help combat myths and misconceptions about contraceptive use and to encourage new moms to adopt modern family planning methods as they returned to fertility.

But during our visit, we observed issues that prompted a reevaluation of our work — and soon thereafter, the evidence behind it. A few months later, our research led to an unexpected conclusion about the value of postpartum family planning and a decision we’ve come to learn is deeply unusual in development: to shut down.

More than $200 billion is spent on development annually, yet evaluating whether projects work — and shutting them down when resources could be better spent elsewhere — remains the exception rather than the rule.

The evidence

We launched MHI through the Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Program, which matches potential founders with each other and provides them with training, mentorship, and seed funding. Every organization incubated through the Charity Entrepreneurship program is based on extensive research on the most promising, cost-effective interventions in global health and animal welfare.

In 2020, CE recommended postpartum family planning as potentially one of the most cost-effective ways of reducing maternal and infant mortality. Unintended pregnancies are a persistent issue worldwide, with significant impacts on both health and well-being. Health-wise, the situation is serious: In 2020, 287,000 women and girls died due to either pregnancy or childbirth. Yet access to family planning is about more than just reducing maternal mortality. The choice of if and when to have children is among the most significant any person will make in their lives: Universal access to contraception is essential in ensuring every person has this choice.

CE’s research drew on several randomized controlled trials, which found that increasing the quality and quantity of family planning counseling in the postpartum period led to significant increases in contraceptive uptake. The idea behind postpartum family planning is simple: By providing consistent counseling on contraception post-birth, programs can ensure women understand their risk of pregnancy and can choose, if they wish, between the methods available to them.

We identified Ghana as a promising operating country because of a combination of a strong health care system, high unmet need (a measure of women who would like to control whether or when they get pregnant but are not using contraception), and low contraceptive uptake, especially in the north of the country. Contraceptive uptake in Ghana is particularly low in the postpartum period, dropping from 35% among women of reproductive age to just 14% three months after birth.

This drop in contraceptive use during the postpartum period is common across most of sub-Saharan Africa. During this period, pregnancy carries heightened risk of mortality for both moms and babies, since the mother’s body has had insufficient time to recover. It’s for this reason that the High Impact Practices list — a research initiative endorsed by USAID, the World Health Organization, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, among others — recommends postpartum family planning programming as a core family planning intervention. Our mission was to develop a replicable intervention model, test it rigorously with the aim of producing highly cost-effective results, and then, if all went well, scale it — first throughout Ghana and then across sub-Saharan Africa.

Adapting RCTs into scalable programming can be challenging. While CE’s research found multiple studies producing substantial change in contraceptive uptake, several of these studies were older, expensive to implement, or conducted in different parts of the world. Our programming at Savelugu Hospital was most closely modeled on a program in Rwanda

which found a 15% increase in contraceptive uptake due to programming in Rwanda.

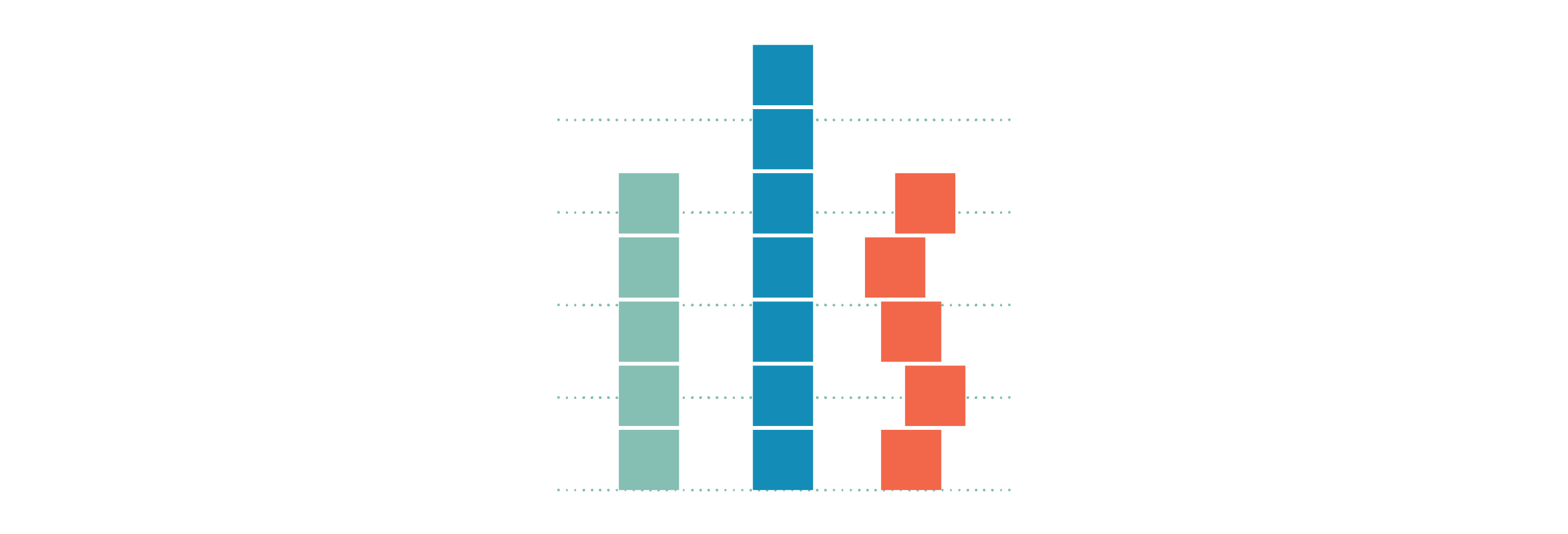

In October 2023, after several visits, many meetings, and two proof of concept testing projects, we started our pilot. We trained just under 50 midwives and nurses from six district hospitals to deliver the intervention. We measured our main outcomes — changes in counseling rates and, ultimately, contraceptive uptake — in a pre-post test before our training occurred and then six weeks after. We aimed to achieve a 10% increase in contraceptive uptake, which we expected to translate into around $105 per disability-adjusted life year averted (a common metric used for comparing health interventions). This level of cost-effectiveness would make our intervention competitive with top charities recommended by evaluators such as GiveWell.

But we had early hints of misgivings. A few weeks ahead of the pilot, Ben visited the bustling CWC clinic at Savelugu Hospital as part of a “proof of concept” project we conducted to refine our programming model. This was designed to iron out implementation issues through a cheaper, smaller set of trainings and follow-up surveys. But observing the talk that day, Ben noticed that mothers seemed disinterested in health workers’ efforts to encourage uptake. More importantly, they seemed to already have strong knowledge of their risk of pregnancy, the various methods available, how they work, and why they might use them.

It was a small sample, but this raised some pressing questions. If mothers already had knowledge of and ready access to family planning, what exactly was our program achieving? And if they knew the benefits of family planning use and had a robust understanding of how these methods work, why were they choosing not to use them?

These concerns were borne out by the results from our formal pilot. On average, counseling increased contraceptive uptake about 3%, much lower than we anticipated. Part of this could have been implementation quality. The facility with the most consistent implementation had increases of 10%, suggesting that the 3% average could be improved. But before taking that on, our intuitions led us to reexamine the literature more closely. This revealed a more fundamental issue: programming to increase contraceptive uptake in the postpartum period likely produces little meaningful reduction in pregnancy risk.

When we looked at a follow-up to one of the largest and ostensibly most successful studies on postpartum family planning — the Yam Daabo intervention in Burkina Faso

— Sarah noticed something we had previously missed. In a single line buried midway through, the paper reported the program’s effects on pregnancy rates: no change. It was not the only study with less-than-stellar results. The sole other study from sub-Saharan Africa — a two-year follow-up study in Tanzania

— also found no change in pregnancy rates, while a study in Nepal found a less than 1% reduction.

Only one study in Bangladesh found relatively promising results —a 19% relative reduction in risk of a short interval between births.

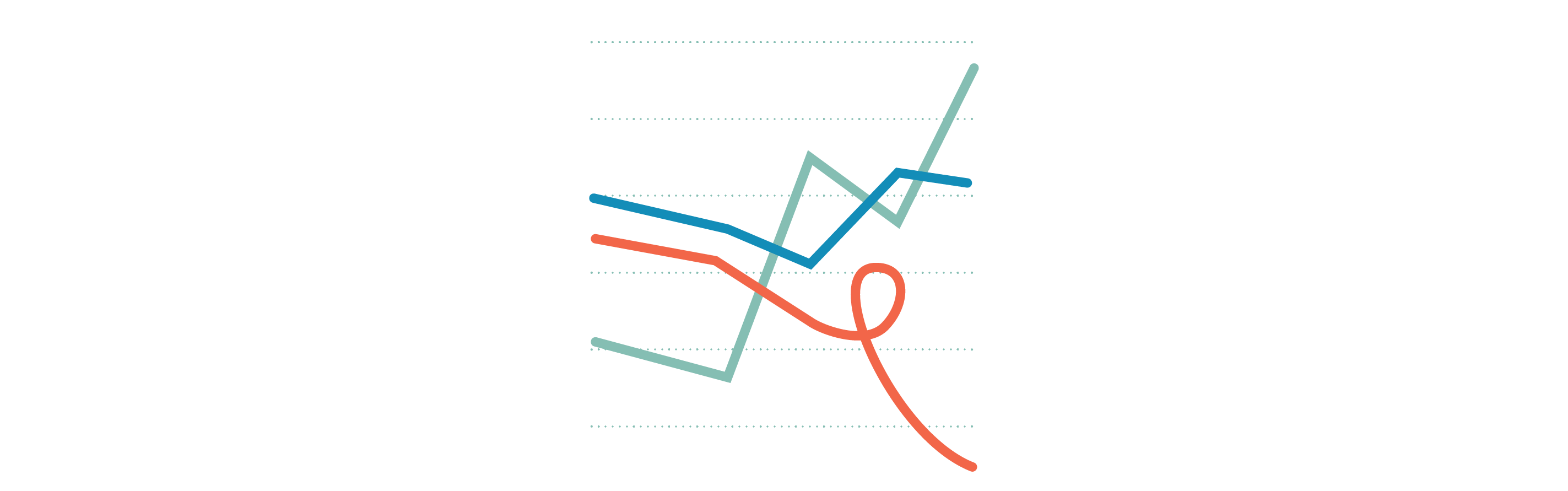

These are genuinely surprising findings. There’s a strong body of work highlighting the connection between increases in contraceptive uptake and decreases in pregnancy rates. CE’s modeling followed conventional wisdom in assuming that general effects from contraceptive uptake would hold constant for the postpartum period, which we now believe is not the case.

Increases in contraceptive uptake are valuable insofar as they allow women to avert mistimed or unintended pregnancies. All of the key impacts of contraceptive uptake — reductions in maternal and infant mortality, increased years of schooling, and greater reproductive autonomy — result from reductions in unintended pregnancies. Without an impact on pregnancy risk, programs promoting contraceptive uptake provide no real benefit — and crucially, assuming limited developing resources, are an ineffective use of time, money, and effort.

Tracking and evaluating metrics that capture endline impact — concrete improvements to people’s health, well-being, or opportunities — are the best ways to ensure programs are actually creating change. In the case of MHI, our intervention’s primary outcome, increased contraceptive use, fails to reliably convert to endline impact. Why might this be?

Throughout the pilot, providers consistently reported that many women declined contraception based on their perceived protection due to abstinence or breastfeeding. Indeed, our pilot found that almost 100% of women reported breastfeeding regularly, and three-quarters were abstaining from sex at six months postpartum. We were aware that prolonged sexual abstinence was a common cultural practice in much of West Africa (many women even leave their marital homes to enforce this behavior). However, the extent of postpartum abstinence caught us by surprise after discussions with multiple experts, both Ghanaian and international, who had downplayed its significance. Similarly, many of the academics and practitioners we spoke with discounted the significance of breastfeeding as a factor affecting contraceptive programming.

Based on this, we trained providers in line with WHO guidelines to counsel that breastfeeding provides reliable protection only when it’s practiced consistently and exclusively, the mother’s period hasn’t returned, and it’s no more than six months postpartum.

However, a number of studies suggest that nonexclusive breastfeeding at 12 months post-birth is only slightly less effective than exclusive breastfeeding at six months — providing comparable levels of protection as typical use of the oral contraceptive pill.

This hypothesis receives further support from the fact that both studies showing no effects on pregnancy rates from postpartum programs were in countries with prolonged abstinence and breastfeeding, while the studies showing positive (though limited) effects on pregnancy rates were conducted in areas with much shorter durations. Put together, abstinence and breastfeeding likely drive results which find that programming increasing contraceptive uptake in the postpartum period has limited effect on rates of unintended pregnancies.

This is the conclusion that led us to a decision we think should be more common in global development. We shut down.

Every charity sets out believing that its work can be transformative. But behind good intentions is the reality that there are limited resources and countless problems. Development funding is not always zero sum, but in most cases money spent on ineffective programs means less resources devoted to the most effective ones. Despite the hundreds of billions of dollars spent annually on development, we lack evidence that most programs work, and there are very few publicly available examples of projects shutting down in light of poor results.

What can our choice to shut down MHI tell us about why projects stumble on rather than close up? What would a culture of greater willingness to accept bad results and shut down look like? And what would it take to shift to that culture in the development sector more broadly?

The importance of measuring endline impact

A lack of evaluation plagues the development field. Less than 5% of World Bank projects implemented since 2010, for instance, have been rigorously evaluated. Only 3% of USAID’s budget goes to external performance and impact evaluations, and what evaluations are conducted rarely meet the agency’s own standards of rigor. It’s even more difficult to assess to what extent the fragmented charity and NGO landscape engages in evaluation, but it’s likely to be just as blind to its own impact — if not more so.

Most charities don’t robustly measure the effect of their programs. RCTs are expensive, laborious, and therefore (perhaps understandably) rare. But even simply measuring endline outcomes — what we actually care about programs achieving — is uncommon. Here again, collecting reliable data is challenging, especially given budget constraints. As a result, many organizations focus instead on intermediate outcomes — but these often fail to tell us if a program is truly working.

An organization may highlight, for example, that they trained 2,000 health care workers, funded a hundred thousand water projects, or distributed one million textbooks. But training and textbooks aren’t worthwhile in themselves; they’re valuable insofar as they produce changes in what we actually care about: health care or education outcomes.

Measuring endline outcomes is difficult, but we should not excuse a lack of measurement simply because it is challenging. There is too much at stake. Without knowledge of how much programs drive the outcomes we care about, donors can’t direct their money to what works best.

Consider that some programs are effective in certain contexts but not in others, or show promise in early trials but prove ineffective when scaled. Such was the case for two Evidence Action programs: No Lean Season, a migration support program tackling seasonal hunger in Bangladesh, and No Sugar, a program in Botswana aiming to reduce HIV rates by educating young girls on the risks of relationships with older men. Both programs received significant investment based on promising RCTs or pilot results, only to achieve little impact when scaled. And that’s okay: Those results allowed Evidence Action to use those resources more effectively.

Other organizations are also leading the way. The Against Malaria Foundation and New Incentives run interventions closely based on RCTs showing highly cost-effective results. More organizations should follow this example. Yet even here there can be issues: AMF does not conduct ongoing evaluations of their work, instead trusting that results from previous RCTs will continue to generalize. Issues with insecticide resistance and net manufactures raise questions about whether bednet distributions consistently reduce malaria rates, suggesting the cost-effectiveness of AMF’s work may be more uncertain than its basis in RCTs would suggest.

To truly understand what development projects should receive more funding and which should shut down, it’s essential for organizations to rigorously evaluate endline impact. Sadly, in addition to this being hard, the incentives to do so are largely absent.

Nonprofits are accountable to donors, not beneficiaries

If a business creates a product that customers don’t want, no one buys it. At least in theory, that means that businesses are incentivized to create the best products for consumers.

In the nonprofit world, organizations are accountable to their donors, not their beneficiaries. If you can’t secure funding, it’s game over. Nonprofits are therefore only held accountable for their effectiveness as far as it affects their ability to obtain further funding. With a compelling story and a strong fundraising team, projects can continue — even scale — without evidence that they work or, even when there is evidence, that they don’t.

One Laptop Per Child, founded in 2005, has provided more than three million low-cost laptops to children around the world with the aim of using technology to improve learning outcomes in lower-income countries. It’s an appealing vision. But multiple studies have found this work fails to provide value due to more structural issues. To OLPC’s credit, their model has expanded to include training and infrastructure upgrades, but the issues with education are far more basic. The average child globally now attends school for just under nine years, yet 70% of children in low and middle-income countries cannot read a basic text at age ten. What use is a laptop when you can’t read anything you might look up on it?

We should expect programs like this — clever in theory, ineffective in practice — to emerge when nonprofits have stronger incentives to win over donors than to help their beneficiaries. The point here isn’t that we should scrap efforts to be ambitious, be innovative, or try new things. But we need to learn from them and adjust course as we go.

MHI was lucky to benefit from a startup-oriented culture that was open and accepting of the possibility of failure. Our advisors and donors alike supported our decision to wind down, which made it a much more feasible option than it would have been otherwise.

This is probably a rare position in development, and there are many examples to the contrary. Heifer International, for example, provides broad-ranging agricultural support to farmers in lower-income countries. It’s best-known for its programs allowing donors to “purchase” livestock for beneficiaries. The value of this work has been questioned, and the results of a 2005 evaluation showed limited effectiveness according to one of GiveWell’s founders who viewed the results. But Heifer International has declined to publish the study, sharing only its interpretation. It continues to fundraise millions for programs based around livestock purchases.

In the face of this lack of accountability, international development experienced a “randomista” movement in the early 2000s, which popularized the use of randomized control trials to assess the value of different projects. GiveWell, touted as the “gold standard” for charity evaluation, draws from this vision, conducting intensive research evaluating the studies and other evidence underpinning the work of promising charities and directing over $2 billion to the most cost-effective opportunities.

This approach is a significant improvement on the prior lack of accountability but has faced criticism of its own. RCTs can fail to generalize, while programs targeting more holistic change are not evaluated due to the difficulty in measuring their more complex or far-reaching effects.

Intense evaluation and project tracking can also become bureaucratic, leading to a recent increase in popularity for “trust-based philanthropy” among many foundations. Trust-based philanthropy has its roots in the broader social justice movement and neocolonial critiques of development spending, with the wealthy having extensive and unearned influence over the lives of the poor. At its core, trust-based philanthropy is about equalizing the balance of power between donors, nonprofits, and the communities they serve by reducing application and reporting requirements and increasing unrestricted and multiyear funding. It’s exemplified by MacKenzie Scott, who has given more than $17 billion over the past four years. Scott’s gifts are given with no strings attached, and recipients are allowed to spend the money however they choose, with zero required reporting.

Trust-based philanthropy has received widespread acclaim, but behind closed doors, we encountered more skepticism. We spoke to six longtime aid workers — ranging from US-based researchers and grantmakers to program implementers working in Africa and South Asia. All were unwilling to speak on record, citing concerns about retaliation, but raised a number of concerns about the practice. One person joked that though they’d love to see a piece critiquing trust-based philanthropy, they couldn’t retweet it because they’d “never be hired again.”

Their concerns are reasonable: Accountability is vital for a flourishing development ecosystem, and donors are the most effective source. Furthermore, nonprofits should not be conflated with the communities they serve. A growing number of funders use the language of “participatory grantmaking,” but the aid workers we spoke to suggested that only a small fraction of these funders gives community members genuine decision-making power over projects or funding. Trust-based philanthropy positions itself as solving development’s structural problem by shifting power from donors to nonprofits. But beneficiaries are left in the lurch. By imposing minimal requirements for monitoring and evaluation, donors make it easy to inadvertently support programs with little value for beneficiaries.

Rigorously implemented direct-to-beneficiary programs — such as GiveDirectly’s cash transfer programs — offer a more radical solution to power imbalances for donors focused on this injustice by placing decision-making fully in the hands of people they serve. Cash benchmarking evaluations — like that of the Huguka Dukore employment program in Rwanda — also suggest these programs may be substantially more effective than many more traditional philanthropic interventions. Despite being specifically focused on improving income through employment, Huguka Dukore “had no impact on monthly income.” Cash transfers, on the other hand, doubled it.

Projects that fail to meet the bar should be shut down

No one wants to shut down. It is hard to accept that the sleepless nights, time away from loved ones, and endless negotiations with an unfamiliar bureaucracy we went through were all in service of a project that failed to achieve its goals. We spent the best part of two years championing an intervention — convincing donors to give us significant funds and overworked nurses to change their behavior — that we now believe brought little benefit and drew funds away from more useful programs.

As much as people around us have been supportive, it is hard not to believe they’d be more enthusiastic if we’d buried the studies and blindly insisted on its success, perhaps trumpeting the many reports of its efficacy from providers which we viewed with strong skepticism.

We went to great lengths to emphasize to our local partners, stakeholders, providers, and women surveyed that we wanted their honesty rather than their praise, but it was a constant uphill battle — one we mostly lost. On visits where we had seen for ourselves that counseling wasn’t occurring, providers would often still insist that our program was helping lots of people, they were absolutely implementing it, and it was driving substantial change. Meanwhile, we received official data from several facilities in our initial proof of concept projects that appeared obviously fake — reports of 100% rates of postpartum contraceptive counseling and contraceptive uptake, levels unheard of in any country.

We were lucky that MHI was a small organization with just three employees when we decided to shut down. For much larger projects and organizations, it’s easy to see how the human cost of closing down becomes a major barrier. Nonprofit organizations are often staffed by caring, dedicated people who may be making personal and financial sacrifices in order to do their jobs. Shutting down requires decision-makers to acknowledge that those sacrifices could have been better directed elsewhere.

Running an organization means taking full responsibility for what it does in the world, both good and bad. Among all the smart, logical reasons it didn’t work — why postpartum family planning seems a poor investment — it is hard for us not to feel that MHI’s failure is our personal failure. Certainly, we would like to believe that MHI’s failures were not from a lack of effort. We designed and distributed a unique system of contraceptive counseling materials, paid a stipend to a nominated “Program Champion” at each facility, and even developed a messaging-based system to give refresher training to providers individually and get photos of counseling directly from the source. These efforts may have been useful. None, however, appear to have been enough to overcome more fundamental issues with the intervention.

Considering where future funding and effort could be most impactful — a project’s “counterfactual”— is critical in seeing why shutting down may be the best available option. Evidence Action’s Beta Accelerator portfolio, of which the No Lean Season and No Sugar projects were a part, exemplifies this approach. It’s this mindset that drove our decision to end MHI.

We may still be wrong. Our pilot was small, and there’s not much evidence out there on postpartum family planning’s impacts on pregnancy rates. Perhaps several new RCTs will be published in the coming years that show our conclusions were premature. But even if postpartum family planning may still be an impactful intervention, we think the odds are low that it’s the best use of the resources at our disposal.

Thinking in terms of bets, or counterfactuals, like this is particularly important given the imperfect systems for development project funding. We spoke to one implementer who recalled how they realized that their intervention was focused on the wrong target area — six months into a three-year project. However, given the choice to return the funds entirely (some of it already spent) or continue on with a mostly ineffective project, they decided to proceed.

The world is complex, and doing good is difficult. We need more examples of projects shutting down to avoid organizations making the decision to continue without acknowledging that their resources could be better spent elsewhere.

Shutting down is a sad occasion but also, in some ways, a cause for celebration: We successfully identified ways to more effectively help the world. Ultimately, that’s what development is all about.