Historically, cities in industrializing countries were often identified with the things they produced. Manchester is where they made textiles, Pittsburgh is where they made steel, and Detroit is where they made cars. These urban identities weren’t confined to heavy manufacturing: New York is synonymous with finance, Los Angeles with movies, and Milan with luxury goods. Nor has the tendency to identify urban areas with specific economic activities fully disappeared: Today, the Bay Area is where they write software and Taipei is where they fabricate semiconductors.

These are all examples of what the sociologist Max Weber called, in a 1921 article The City,

producer cities: urban areas organized economically around some specific trade or particular manufactured goods that could be exported to other areas.

In contrast to these producer cities are what Weber called consumer cities. These were places organized economically around a specific set of residents with rights or privileges to some stream of income, like land rents or taxes. Weber used historical Beijing, which was centered on government officials, and Moscow, centered on landowners collecting rents from peasants, as examples. A contemporary example is Dubai, which grew rapidly around oil revenues.

Weber attributed the economic development of Europe relative to Asia to the predominance of its producer cities. The advantage he posited wasn’t because producer cities were necessarily larger — Beijing was perhaps 10 times as large as Manchester on the eve of the industrial revolution — but because producer cities had a higher capacity for innovation. They were dynamic.

Because producer cities are dependent on trade with other cities or countries, they have more incentive to innovate to gain market share. Consumer cities, on the other hand, are more likely to rely on rent seeking — and therefore experience economic stagnation. Moreover, innovations in one producer city can spill over to other producer cities through supply chains (cheaper steel in Pittsburgh makes for cheaper cars in Detroit) — but anything that benefits a consumer city likely comes at the expense of another city or region (like higher rents for agricultural tenants).

Weber’s city classification was a useful framework for understanding the historical processes of urbanization and economic growth. But how useful is it in understanding economic growth — or the potential for economic growth — in the modern developing world?

It isn’t hard to come up with developing cities that fit his scheme. Zhengzhou, China, is home to a Foxconn manufacturing plant that employs around 350,000 people and produces about half of all new iPhones. On the other end of the scale are consumer cities like Luanda, Angola, a city built around oil revenues and of which The Economist said: “Shiny shopping malls are filled with everything the Angolan heart could desire, from gourmet food to the latest fashions and car models. Prices are wildly inflated. Virtually everything … has to be imported.”

The economic and demographic context today is of course quite different from that of 1921. The City centered on agrarian nations and emerging cities with populations in the hundreds of thousands. Modern developing nations are already heavily urbanized compared to historical norms. Some of the poorest countries in the world are nevertheless home to cities with tens of millions of residents.

But we can still take a Weberian approach and ask whether poor countries home to producer cities developed — and will continue to develop — faster than poor countries host to consumer cities. We just also have to consider whether the relatively early urbanization and unprecedented absolute size of cities in these poor countries has locked them into a consumer city-like economic model — and stifled the opportunity for sustained development.

A short history of urbanization and development

Let’s start by establishing how the relationship between urbanization and economic development has changed since Weber first made his observations.

The figure above shows that in both 1913 and 2020 higher urbanization rates are associated with higher GDP per capita.

In 1913 the poorest countries were barely urbanized, often with less than 10% of their population in cities. The richest places had urbanization rates of 40%–50%, with one big outlier in the form of the U.K., at an urbanization rate of 75%. Over the last century, however, the entire world has become more urban — as of 2007, over half of the global population now lives in cities.

As a result, the association between urbanization and GDP per capita is no longer as steep. In particular, there has been significant “poor-country urbanization.”

By 2020, even the very poorest countries had urbanization rates of 20%, and some reached 50%.

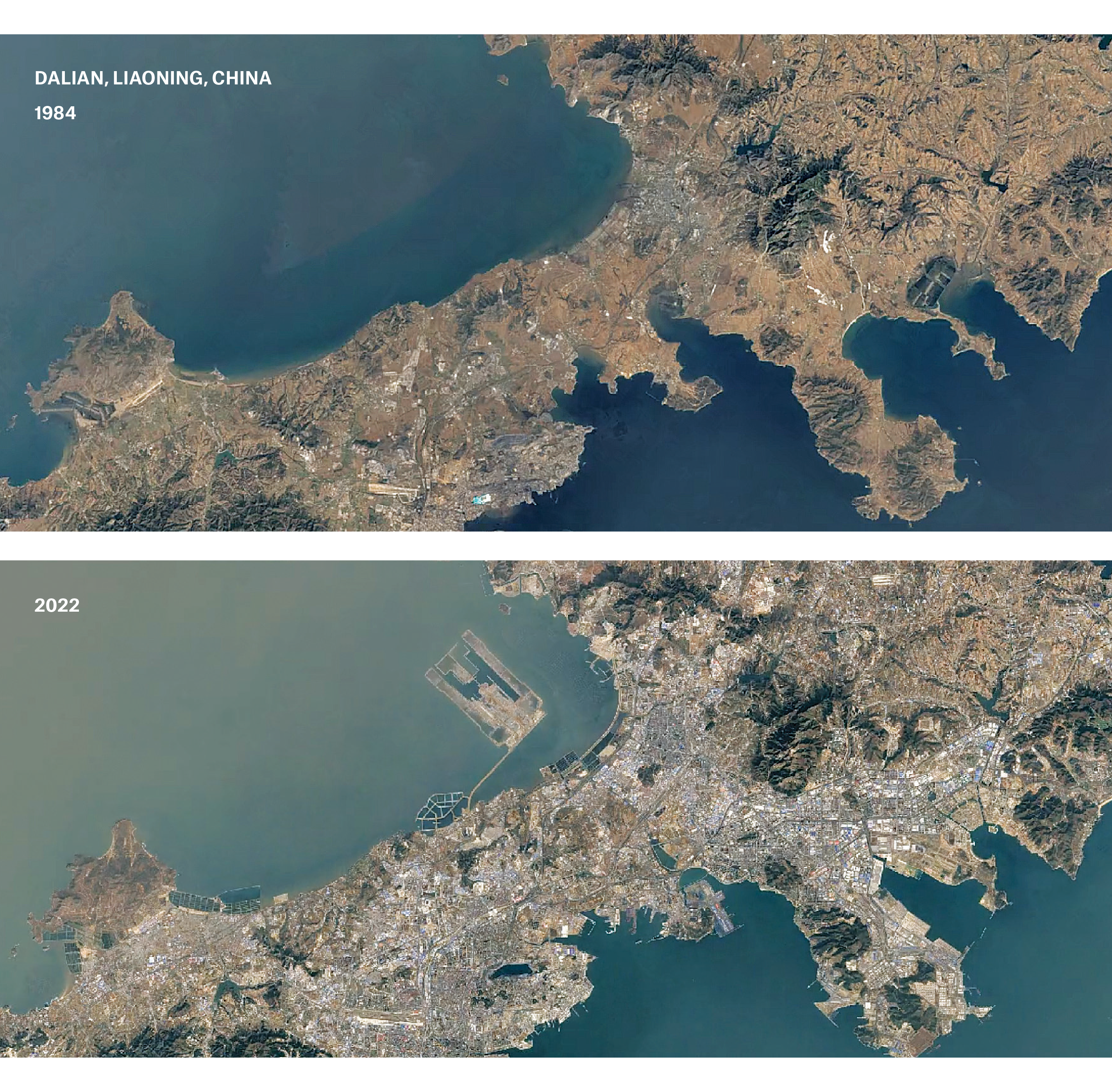

You can get a sense of this shift by looking at specific examples. China has an urbanization rate of around 64%, in recent years passing Poland and Austria.

Each of these countries are emerging or established industrial producers. But their urbanization rates are similar to, or below, those of Gambia (64%), Ecuador (65%), and Algeria (75%), none of which approaches our idea of an industrial powerhouse. Perhaps more surprising is that all these countries are far behind, for example, Gabon (91%), a West African country with a per capita GDP below $9,000 but with proportionally more city-dwellers than the United States (83%), United Kingdom (84%), or South Korea (81%).

Places like Algeria, Ecuador, Gabon, and Gambia have urbanized rapidly, but migration to cities did not result in the same economic growth or industrialization as it might have 100 years ago. That’s consistent with, but not definitive proof of, the presence of consumer cities in these places. The worry is that places like this will remain stuck at these low living standards because their cities are not providing the same engine of growth that exists in places like China.

Natural resources and city types

For some deeper evidence on the characteristics and prevalence of consumer cities in the developing world, I’m going to rely on a study that Remi Jedwab, Doug Gollin, and I did several years ago.

We used Weber’s ideas to classify developing countries by the type of cities that tend to be present there. To do this, we looked at GDP relative to either natural resource exports (which consumer cities rely on) or the total output of industries like manufacturing and finance.

Countries tend to cluster into a few groups. The first includes countries like Algeria, Angola, and Gabon, which continue to urbanize, but have low industrial output and high natural resource exports. Their urbanization mainly occurred via consumer cities built on resource rents. In contrast, places like China, Costa Rica, and the Philippines are also urbanizing, but have done so with relatively high industrial output and little in the way of resource exports. Their experience is consistent with the presence of producer cities. There’s also a group of countries like Bangladesh and Tanzania which are not very urbanized (under 40%) and don’t have a lot of natural resources, but for whom industrial output accounts for a large fraction of economic activity. These places appear to have producer cities — they just haven’t quite taken off yet.

Using this classification system, we documented clear differences in the characteristics of urban areas in countries with consumer cities or producer cities. Most noticeable was the composition of employment. In countries with consumer cities, a much larger fraction of urban residents work in nontradable services like retail sales, entertainment, and personal services, like maids or cooks. Countries with producer cities naturally have larger fractions of workers in manufacturing and finance or professional services, and a much smaller share of service jobs.

This difference in workforce is reflected in the cost of living, which is higher in places with consumer cities. These cities have to import basic goods, and the personal services their workers engage in tend to be low productivity, so they are quite expensive to live in. In that sense, consumer cities are similar to resort towns or vacation spots: they are where money gets spent, but not where things get made.

Importantly, these differences in living standards show up in other measures. All else equal, countries with consumer cities have higher poverty rates and a larger share of population living in slums, as well as lower shares with access to improved water services or sanitation. We also found evidence that the returns to schooling are lower in countries with consumer cities.

That “all else equal” is important. It means that even if a country dominated by consumer cities reaches the same level of GDP per capita and urbanization as a country with producer cities — which is possible given sufficient flows of natural resource exports, à la Dubai — there remains significant distributional issues. The revenues coming from those resource exports are not getting turned into investments in population health or human capital. That is a huge check on potential future growth.

The epidemiological transition

The evidence so far points toward significant differences between developing countries with consumer and producer cities. But as we have seen, urbanization across the entire developed world is much higher than the historical norm. This is due in large part to a radical change in demographics over the last 75 years, and it has made all developing cities more “consumer-like” than they would otherwise be — regardless of their resource exports or manufacturing base.

For most of human history, cities were death traps. Crowded buildings, unsanitary conditions, and a lack of medical knowledge meant that communicable diseases ran rampant. The same communal infrastructure that allowed cities to exist — water pumps, drainage ditches — was often the very source of disease that prevented cities from growing further.

In the late 19th and early 20th century the crude death rate (the number of deaths per 1,000 residents) in industrializing cities like New York or London was between 20 and 30. In poorer countries at the same time, crude death rates were on the order of 40 to 50. To give some context for those numbers, the crude death rate in 2018, just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, was around 8.7 in the United States, around 11 in a rapidly aging Japan. and only reached as high as 15 in select places in Eastern Europe or central Africa.

Despite much higher fertility, industrializing cities at the turn of the 20th century had death rates barely below their birth rates. They didn’t grow as a result of expansion within their population, but because immigrants — either from rural areas or abroad — kept arriving.

That dynamic changed in the 20th century with the epidemiological transition. Due to advances in medicine and sanitation, high mortality rates from infectious disease plummeted, life expectancy increased, and chronic diseases — cancer, heart disease, diabetes — became the primary causes of death.

Urban death rates continued to fall after the introduction of effective antibiotics such as penicillin and streptomycin and vaccines against yellow fever, polio, and measles, as well as concerted eradication campaigns against diseases like smallpox. Those efforts saved millions upon millions of lives in developing countries, and in particular in cities. By 1960 the crude death rates in cities like Lagos or Kinshasa were well below 15. By the early 21st century almost all major cities in the developing world had crude death rates below 10. Not only do these cities now have death rates as low as those in rich nations, but they also have death rates well below rural areas — a reversal from the past.

This triumph of public health was most prominently seen in the massive growth of urban populations. In addition to lowering crude death rates, it made immigrating to them from rural areas more attractive. Remi Jedwab and I calculated how much urbanization in developing countries could be attributed to the epidemiological transition using a simplified model of internal migration and population growth. We estimated that by the early 20th century, urbanization rates were 10 percentage points higher (e.g., 30% rather than 20%) than they otherwise would have been, and that urban populations were almost 60% larger. Much of the upward shift in urbanization rates over the course of the 20th century was due to lower mortality.

What does this have to do with consumer and producer cities? Age structure wasn’t something that Weber considered, but I think the logic here is consistent with his reasoning. Producer cities are predominantly populated by working-age adults. This holds true across all time periods; producer cities are attractive to working-age adults because of wages and the availability of jobs. But this selection effect was even stronger before the turn of the 20th century, because it was exacerbated by high mortality rates among the most vulnerable age groups: children and the elderly. As a result of the epidemiological transitions, cities in the developing world saw their populations of consumers (children and the elderly) grow relative to their populations of producers.

Jedwab, in separate work with Daniel Pereira and Mark Roberts, documented that developing countries have what they call “cities of babies.”

In poor countries, there are about two children for every three working adults in cities. In rich countries, that ratio is only one to three. And that holds true for the past. During the period in which today’s rich countries industrialized, the ratio of children to working adults was still lower than in developing countries today.

Age structure wasn’t the only effect of the epidemiological transition. It also changed the nature of developing cities by increasing their share of slums. Jedwab and I identified the mortality decline as being responsible for about half of the expansion of slums in developing cities during the last 70 years.

Slums lack major infrastructure, and this leads to lower living standards than other urban areas. But that same lack of infrastructure makes slums much more flexible in absorbing new people. The burgeoning city populations following the epidemiological transition had to go somewhere. Slums were often the only areas that could keep up.

Slums don’t fit neatly into Weber’s classification. Slum residents aren’t there because they have some outside income that they are consuming, like the retirees in The Villages in Florida or emirs in Dubai. Producer cities do sometimes have slums, as the history of a place like Manchester demonstrates. But the slums themselves aren’t generally the centers of production.

The changes in age structure and slum share that followed the epidemiological transition don’t, by themselves, mean that cities are consumer cities. But because they create a population that is less capable of participating in the economic life of the city they potentially attenuate the ability of a producer city to generate significant economic growth.

Economic growth in developing cities

The data point toward urban growth in developing countries taking the form of consumer cities rather than producer cities, although this is a matter of degrees, not binaries. We also know there isn’t necessarily a difference in living standards; consumer cities can be, and often are, as rich or richer than producer cities. To the extent the distinction in city type matters for development, it has to do with the dynamic effects of city types on subsequent economic growth.

Gilles Duranton has done significant amounts of research on urbanization and growth, and has also written a very readable overview of that literature.

In it, he describes reasons that developing country cities have been less economically dynamic than their historical peers. One is that the urban system of developing countries — their entire collection of cities — tends to be more concentrated in a single primary city when compared to rich countries. A common way of measuring this urban primacy is by taking the ratio of the population of the largest city to the population of the second largest.

In Argentina, for example, the Buenos Aires metro area dominates the urban system. Its roughly 14 million residents make it about 10 times larger than the next biggest city (Córdoba). There is a similar story in Angola, where Luanda is about nine times larger than Lubango. By comparison, in Japan the Tokyo metro area is only about twice as big as the Osaka metro area, and in the United States the New York metro is only about 1.5 times larger than Los Angeles.

A potential issue with significant urban primacy in places like Argentina or Angola is that it limits the circulation of workers and knowledge across locations. It can create so much congestion that any positive productivity effects of having a large population are overwhelmed. Urban primacy is more likely to develop around consumer cities as resource rents and taxes tend to flow to a central seat of government, and hence these cities get “too big” to maximize economic growth across the whole urban system.

This doesn’t mean that big cities in developing countries have no positive economic effects, but it may be that such an arrangement is not as good as it could be. In a separate work Duranton and Diego Puga distinguish three kinds of positive agglomeration effects arising in cities: sharing, matching, and learning.

Sharing boils down to specialization; common demand for a product (whether integrated circuits or Thai food) makes it plausible and profitable for a firm to provide it. Matching means that not only can you find a supplier of a product, but you’re more likely to be able to find just the right supplier to fit a particular need. Learning involves knowledge spillovers across firms and individuals, whether formal or informal, as they interact in the city.

There is plenty of evidence for positive agglomeration effects overall — larger cities tend to be more productive than small cities. But if you dissect the evidence for sharing, matching, and learning, it looks as if those effects are primarily driven by the sorts of economic activities exclusive to producer cities. Vernon Henderson, Todd Lee, and Yung Joon Lee looked at South Korea during its period of urbanization and industrialization.

They found that agglomeration effects are strongest in heavy industry and modern manufacturing (e.g., electronics) but negligible in industries such as textiles and food processing. We can’t rule out similar effects in consumer cities, but to date the evidence for them only exists in what we could consider producer cities.

Even leaving aside agglomeration economies of cities, the differences in economic activity between consumer and producer cities may lead to slower growth in the former. We have widespread evidence that productivity growth in industrial sectors like manufacturing is consistently higher than in nontradables like education, health care, and personal services. By concentrating employment and production in such nontradables, consumer cities are bound to have lower productivity growth. We often credit economist William Baumol with identifying the implications of these differences in productivity growth rates across sectors. Of note: Baumol’s original work on this topic, from 1967, was subtitled “The Anatomy of Urban Crisis.”

That work traced the financial woes of slow-growing cities in the developed world to the shift away from industry — and into services. To the extent that consumer cities are concentrated in things like personal services, this would imply slower growth in the long run.

One of the reasons manufacturing allows for higher productivity growth is global knowledge spillovers. Dani Rodrik documented what is called “unconditional convergence” specifically in manufacturing productivity across countries: Places with lower productivity tend to have faster productivity growth, and thus are catching up to the frontier over time.

But this same dynamic does not appear to hold for agriculture or services. Service-oriented consumer cities aren’t getting the same boost. As a result, developing countries are facing what Rodrik calls “premature deindustrialization,” or the tendency of manufacturing to shrink as a share of economic activity in countries that are still relatively poor.

The case for optimism in developing cities

Despite all the reasons to worry that developing countries have urbanized themselves into an economic cul-de-sac, we need to be careful judging them against the historical experience of Western Europe and the United States — regions which industrialized and urbanized in a very different technological and political environment. In those places urbanization often — though not always — took the form of industrial producer cities and subsequently reached the high living standards we see today.

That does not mean this is the only way to reach those living standards. Developing countries today may well be taking the most direct route in a world where they can learn from the frontier. Sub-Saharan Africa, as an example, has almost universally skipped the installation of landline phone networks and gone right to widespread mobile phone coverage. We never think that this failure to follow the historical path is bad for economic growth.

In that sense, it may just be wrong to classify many developing cities as consumer cities. While the resource exporters mentioned above fit Weber’s definition well, for many others it is ill-suited. It might be better to call places like Dhaka “latent” producer cities: They didn’t grow because of some resource rent or particular industry, but the potential is there to take advantage of agglomeration via sharing, matching, and learning. They could be producer cities given the right conditions.

The right conditions would include a useful transportation network. A lack of good transportation means these cities aren’t operating as unified wholes and don’t interact with other cities economically. A thick body of recent research from India and sub-Saharan Africa shows that improved transportation networks — both rail and road — lead to significant jumps in economic activity and living standards.

Often those benefits arise from cities being able to specialize in an industry or industries, solving the problem that Duranton noted regarding homogeneity of production. The optimistic view here is that we may be able to unlock growth through technologies like mass transit that we know how to provide.

And of course developing world cities in the modern day are, ipso facto, different from those that developed in the past. Weber’s producer cities employed a large fraction of labor in specific industries precisely because the technology was so bad that it took an entire city working together to produce enough steel or cars or textiles to meet demand. With today’s technologies there is just no need to organize a city around an industry in the same way.

Ed Glaeser, Jed Kolko, and Albert Saiz made a version of this argument for rich countries back in 2001.

Their article is titled, suggestively, “Consumer City,” but they define it in a different way than Weber. Their contention is that cities not only have agglomeration effects for production, but also agglomeration effects for consumption. From this perspective, sharing and matching means having a proliferation of choices over things like restaurants and entertainment or being able to find the perfect coffee shop or bakery. These things make urban areas more attractive, even if they don’t necessarily lead to higher productivity. A similar kind of argument holds for the urban growth Jedwab and I found following the epidemiological transition. Once mortality in developing cities dropped, they became a much more attractive place to live, and even if that changed their economic structure and slowed growth, it remains an absolute triumph of human ingenuity and public health policy.

Weberian consumer cities, whether they are in poor countries living off resource rents or rich countries living off pensions, are going to be a drag on economic growth. The Villages is obviously not where the next unicorn or Foxconn plant will be from. A Weberian producer city like Zhengzhou is a much better bet. But in the Glaeser, Kolko, and Saiz view, either city is a more desirable place to live compared to a small town or rural area.

Without question, urbanization in developing countries proceeded in a different way than in the past. Developing countries are more urbanized at every level of income, and have different kinds of economic structures. Some of that occurred via Weberian consumer cities based on resource rents or other outside flows of income, and some of that occurred via Weberian producer cities centered on specific industries or products. But many of the other cities are hard to classify. A plausible and optimistic view on those cities is that they are not producer cities driving growth just yet. But, with sufficient investment in infrastructure — enabling agglomeration — they have the potential to become so.