The thing that came down right beside us was three meters high with a massive articulated body. A bug, really, Chelicer style. Eight crooked legs out from a central hub like all the mobile life here had, but most of what we’d seen was gracile, delicate, and came up to your waist. Even the Farmers — which we’d pegged as the most advanced species around — were only a meter and a half tall, and most of that was stilting limbs. This thing was not gracile. Every segment and joint of it was ridgy, armored, and spiky. It was dun and khaki like the planet’s dust, but too big to have hidden anywhere nearby, towering over the scrub. There were spread vanes like sails projecting from its back, but it couldn’t have flown under organic power. It must have weighed five tons.

We just stared. In that moment, when we could have run or called for help, we goggled at it. The stalked globes of its eyes looked back, devoid of living connection. A vast armored monster, airdropped from nowhere.

I saw the motion, off on a neighboring hillside. There was a second monster out there, surprisingly hard to spot. It hunkered down, drawing its limbs in.

Chunk! That same sound. The thing on the hillside was gone.

A second later it was on us, coming down right in front of Merrit. I thought of mechanical advantage, the tricks you could do with a rigid exoskeleton. I thought of fleas, but on an absurd macro scale. It jumped and came down on eight legs that must have been shock absorbers par excellence.

Chelicer life doesn’t quite have a front or a back, built around that hub of legs. The mouth is on the underside and that’s what this thing tilted at Merrit.

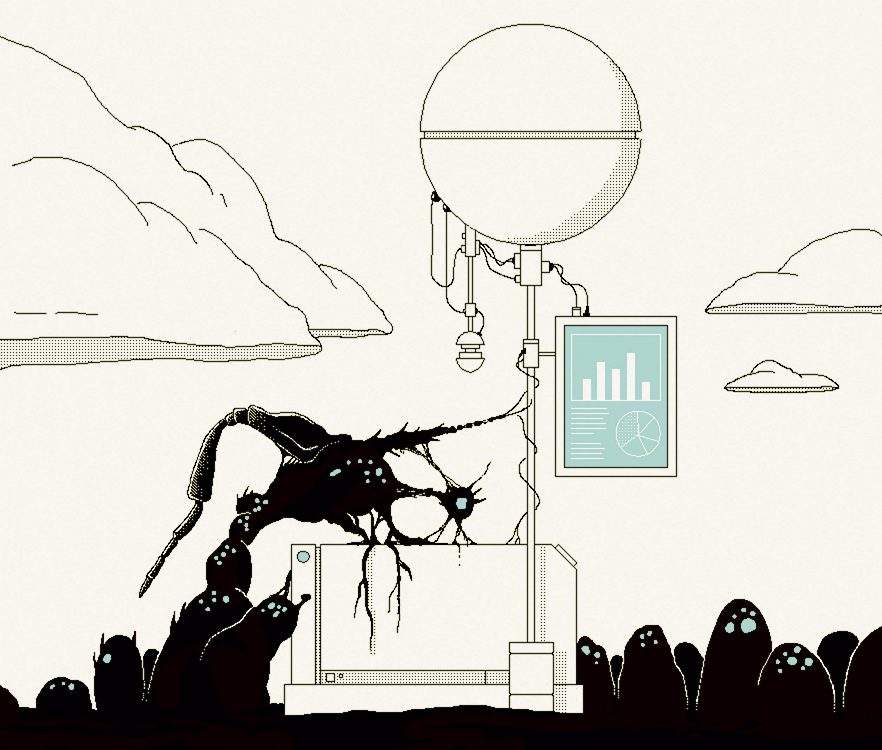

I’d dissected some of the Farmers and they had an arrangement like eight knuckly stumps to mumble over their food with. These new arrivals had a setup like a sphincter made of scissor blades and nutcrackers, more an industrial process than biology. We’d seen what those tools had done to the weather station already. Right then we were more concerned with what it did to Merrit.

He was just crouched there, midway through sifting the wreckage. The monster took instant offense. Its mouthparts extended out and just … macerated him. Chopped and crushed so that in a heartbeat there was nothing left that looked remotely human, just a wadded bloody ball of flesh and splintered bone and rags of suit.

Greffin and I started shooting. Our guns were so badly printed you could see the mold lines. They chewed up their own mass for ammo in a spray of flechettes. True to our miserly resource budget, most of that barrage just slanted off the things’ carapaces, and I knew we were both going to follow Merrit into extinction, carved up and spat out with alien contempt. Except then Greffin hit a joint, and one monster was suddenly down a leg. That, apparently, was enough. We watched them ratchet down for takeoff, still shrugging off our fire, then ping upward. I recorded the flight of one, desperately trying to keep it in my field of vision. Without that, who’d believe us? Alien mega-fleas utilizing sheer mechanical tension to jump a half kilometer at a time.

We bagged what was left of Merrit. And I grabbed the leg when the skimmer came for evac. Because it was proof that here be monsters.

The Farmers had been the tipping point, the reason to establish a human presence planetside. Yes, 14d was a unique world, unknown alien ecosphere, all that. But if it hadn’t held anything useful then the Garveneer would have focused elsewhere in the Chelicer system. And if the world had only offered mineral wealth, we’d have a robot mining operation stripping the place instead. All that unique ecosphere would have been flensed from the planet’s surface as an incidental side effect of our efforts. But on this world, the valuable thing was the biology, which needed more finesse. A human presence on the ground. Meaning a whole team of us thawed off the shelves and given this chance to justify our existence on the payroll.

Which was now under threat, as were we. We evacuated back to the farms with our grisly souvenirs.

The Concerns that have spearheaded humanity’s expansion from star to star have refined an efficient system for exploiting exoplants. When a Concern builds farms, that means a continent’s span of identical fields, robot tended. Everything growing and being harvested at an accelerated rate, processed and dried for minimal weight in transit. Turned into the Ship’s Reconstitute we’re all thoroughly sick of eating. The stuff from the Chelicer farms can look mighty good in comparison, which is a shame because a bite would kill you stone dead. But then they’re not our farms. They’re a thing the locals were doing long before we arrived.

The locals — Species 11 — are like spiders only ganglier. Four stilty legs interspersed with four spindly arms, and a hub of a body in the middle, high enough to come up to your waist. We called them Farmers from the start because it’s what they do: tend great stretches of this one crop. Not even a very exciting-looking crop, sort of a warty purple potato-looking thing, except it turns out to be superefficient at concentrating the elements in the crappy soil they’ve got here. Many of which elements are useful to us, for our superconductors and our computational substructures and all that good stuff. When we discovered that, you can be damn sure we moved in and took possession double time. Built our processing plant and started making off with a big chunk of the crop.

What did the locals think of this? My professional xenobiologist’s opinion was they didn’t think a damn thing. They didn’t react at all. The whole farming schtick they had going was just instinct, like ants, only they didn’t even defend anything. When they got in the way of the machines, they got chewed up. We thought at the time they’d evolved with no natural predators.

We sure as hell were wrong about that.

Greffin and I made our reports. The dozen on-planet crew came to commiserate, meaning get the gory details. We told everyone to carry a gun and know the emergency drill. Chelicer had an apex predator we hadn’t known about. After which cautionary tales, I was left facing up to the mission’s biggest pain in my ass, namely FenJuan.

FenJuan had screwed up royally on some past previous assignments, was my guess. They’d been something senior, and something had gone south in expensive ways. Meaning FenJuan slumming it on our team was an invisible mark against every one of us, because their personnel file came with baggage. Worse, they were my immediate colleague in biosciences, the two of us responsible for figuring out the local biochemistry.

“Stort,” they addressed me, frosty as always.

“Fen,” I replied with just as much love.

“My samples?” they said. Because they didn’t do fieldwork, just like they didn’t do basic human interaction, just sat at base camp and bitched.

And I’d given them samples previously. I’d cut a chunk out of a dozen critters on four other excursions and brought them back. And I’d just seen a work colleague turned to paste by some local monster-bug neither my nor FenJuan’s science had accounted for. But in the Concerns you don’t get time off for inefficient foibles like grief or trauma, so I made do with snarling at FenJuan that they’d had all the damn samples they were getting from me and if that wasn’t good enough then maybe they were the problem.

“When I say, ‘Get me a selection so I can run comparative studies,’” they snapped, “I do not mean just go snip bits off the Farmers and call the job done. A man is dead because we don’t understand the world here.”

Which was turning it back on me, making it my fault. And which wasn’t true to boot. I told them that if they were having difficulty distinguishing between samples maybe they didn’t have the basic analytical skills required for the task. The structures that they’d pegged as the local equivalent of a genome were probably just some essential organelle that every damn beastie possessed, and the real genome-equivalent had gone completely under FenJuan’s radar.

“You want a sample?” I asked FenJuan. “For real? Cut your own out of this. You can be absolutely sure it doesn’t come from a Farmer.” And I pointed them at the leg, the one we’d shot off the big bouncing bastard.

Shouting at people works, when you’re not allowed time off to process death. Works remarkably well, if it’s the only outlet you’ve got. Just as well. There would be plenty of both shouting and death in everyone’s future.

I liked to sit outside to complete my reports. Chelicer has good sun, if you’ve had the treatments to ward off skin damage. I wrote up my thoughts on our giant killer flea problem, watching the Farmers pick their way across the vast fields of “Species 13 Resource” as per official Concern designation, or the Chelicetato as our vulgar parlance had it. They groped over each tuber in turn, then pissed out the right chemicals to help the things grow. The Farmers were a remarkable find. We’d have gone way over budget making robot gardeners even half as efficient. Worth fighting off a few giant bugs for.

Past the processing plants, the elevator cable stretched into forever. Up there was the Garveneer, our home away from home, taking every processed tuber we could hoik out of the ground. And our little outpost here was just the beginning. There were tens of millions of Farmers all over the planet, wherever the conditions suited their crop, all ready to become part of the industrial agriculture of the Concerns. We’d struck the jackpot when we surveyed Chelicer 14d.

Greffin had been going through recent survey images, looking for monsters. She sent me what she found. Holes like burrows I could have driven a ground-car into, written off as geological because nothing we’d seen could have made them. Now we knew better. Maybe the monster fleas had emerged only recently. Maybe there was a cicada thing going on, killer flea season. We made some recommendations for the next security meeting, and I did a tour of the turret guns that had been put in with the processing plant and never needed since.

Doing that put me in FenJuan’s orbit and I braced myself for the sandpaper of their company. They were deep in analyzing the giant leg, though, or thin-sliced samples thereof. They had a few dead Farmers too — there were plenty of aimless ones not working, now we’d harvested their plots.

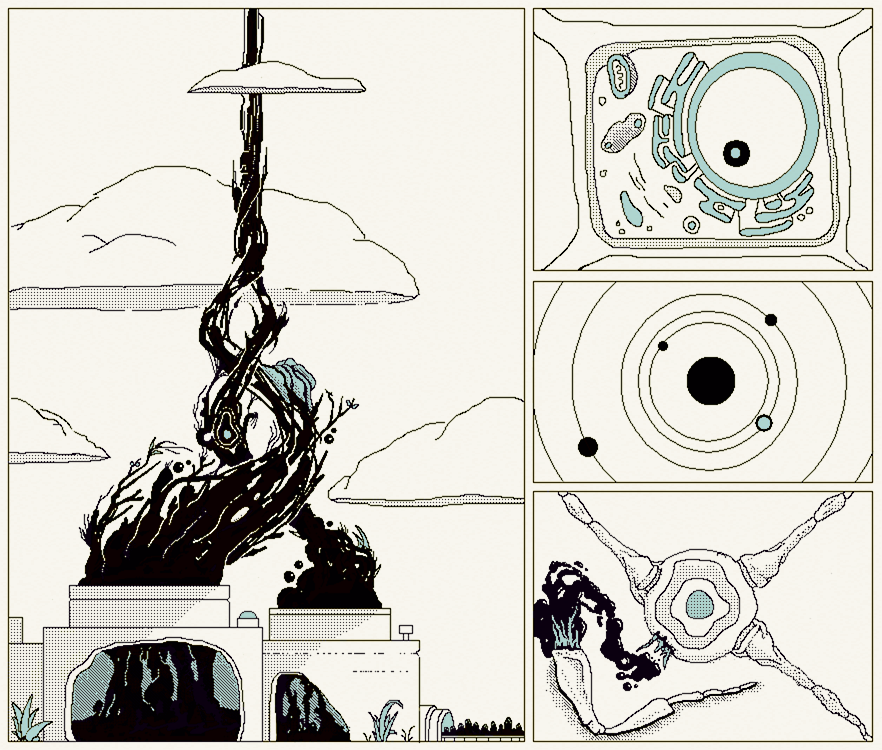

“Stort,” they said, not the usual bark, but thoughtful. On the screens was a variety of different views of microscopic-scale Chelicer cell structure. The spiral-walled cones that FenJuan reckoned were hereditary information, and that they’d been unspooling and trying to decode. Sections had been flagged up on each, identical one to another.

“Junk DNA,” I said, and waited for their usual invective. It didn’t come, though. FenJuan actually nodded a little, a tiny iota of acknowledgment I’d said something that wasn’t stupid. And Earth life accumulates a certain amount of genetic junk, right? Stuff in the genome that’s been switched off, acquired from bacteria, or from benign transcription errors carried on down through the generations. But FenJuan reckoned something like 90 percent of any given beastie’s hereditary was this unused junk.

I wanted to say they were imagining things. I wanted to say it was a crap planet with crap aliens who had crap hereditary code, and us coming along to exploit them was the best thing that could have happened. That was how my encounters with FenJuan generally went. It was basically entertainment for the rest of the team.

I didn’t say any of that. FenJuan and I looked at each other, not quite ready to bury the hatchet, but maybe agreeing there was a bigger problem out there to save that mutual hatchet for.

The attack came the next day, and we weren’t prepared.

I heard the sound, distant, echoing across flat farmland from the dry hills. Chunk. For two whole seconds I was thinking some piece of machinery had gone wrong and how that was someone else’s problem. And then the first of them came down, just like before. Crashing onto the roof of the processing plant hard enough to buckle the plastic composite. Leering over the edge like a gargoyle. I swear it was twice the size of the one that killed Merrit.

I was shouting. Most of us were shouting, but I still caught a rapid heavy drumroll underneath the human noise. Chunkchunkchunkchunkchunkchunkchunk…

They started dropping down all round us. We were running for the plant, because it was the most reinforced building and that was the emergency drill. Someone got word to the guns that their services were needed, and they started running friend-or-foe algorithms as a dozen human beings fled frantically into their arcs of fire.

One of the death-fleas crashed down in front of me, outspread sails barely slowing it. The articulation of its legs popped and twisted, absorbing the force of impact. A gun hammered chips out of its carapace. It lunged forward and snipped someone — one of the resources team I think — right in half with its scissor-blade face. I screamed and just about ducked through the shadow of its wings, not knowing if I’d get killed by its jaws or our own turrets.

Most of us got inside. They didn’t break in after us, but only because they didn’t try. Maybe object permanence isn’t a big thing on Chelicer: Once we were out of sight they seemed to forget us, through they chewed up all the guns.

Through our cameras, we got to see all the rest of what they did.

The Farmers, it turned out, had natural predators. Or they did in death-flea season. The monsters went to town, mostly on the Farmers that didn’t have anything left to farm, because they were just milling about. It was a massacre. And though they were weird alien spider guys, and you can’t really anthropomorphize that, we were all surprisingly cut up. It wasn’t that they were getting slaughtered out there. It was that they were ours. Our livelihood, our profit, the injection of resources that was earning us our wage-worth.

The massacre was monopolizing our attention, so the real damage went almost unnoticed until the earthquakelike convulsion that cracked every wall and trashed the processor floor. For a moment the problem was so big I couldn’t work out what had happened.

The elevator cable. Something about it — maybe just that it was the biggest thing around — had drawn their ire. A half dozen of the bastards had jumped to it, and those mouthparts had sawn through the supertensile material like it was string.

That took a long while to clear up. The actual cable was, after all, a long weighted strand that stretched a good way out of atmosphere and into space, and our actual ship was tethered at the halfway point. The Garveneer decoupled sharpish, you can be sure, and the vast length of the cable, cut free at its anchor, just vanished upward and sideways like the blade of God’s own scythe, on its way toward the outer reaches of the system.

We were stuck on-planet for some time, and we’d just had it demonstrated to us that the death-fleas were more than capable of carving their way into our compromised fortress if they wanted. Yes, our lords and masters in the Concern could shuttle us back to orbit, but that would require circumstances to fall into a very narrow gap indeed. That (1) it wasn’t worth continuing work on Chelicer 14d, and (2) it was actually worth retrieving us, rather than writing us off.

You can imagine the mood on the ground as we waited for their decision. We all gathered in the surviving common space and tried to convince ourselves we weren’t screwed. All except FenJuan, who didn’t do social graces, but just kept on studying the samples, which our remaining instruments couldn’t tell apart.

In the end, after they’d left us hanging for five days, there was a meeting. A handful of us on a staticky link to the chief director safe aboard the Garveneer. We were ready to be bawled out for a colossal loss of resources. That was the very best we thought we’d get. Instead, though, the Great Man was onside. The harvest from Chelicer had been very good indeed, solving a variety of rare elements shortages none of us knew the Concern had. This world we had worked on was the new hope of further human expansion. If only we could solve our little pest problem.

“We need to keep you folks safe,” said the director heartily. I looked over the recommendations. What they actually wanted to keep safe was the harvest, of course, which meant the Farmers. By then we had images from all over the planet of sporadic attacks on Farmer colonies. Death-fleas picking off the weak. Nothing as sustained as we’d seen at our base camp, but plainly a part of the circle of life in these parts.

“Our engineers up here are working on a new cable,” the Great Man told us. “But drones, too. Hunter drones. A whole fleet of them. We can justify the cost, given the potential resource revenue you’ve demonstrated. We’re proposing a global initiative to wipe out these things.”

“Wipe out the species, Director?” FenJuan clarified.

“Given the losses we’ve sustained and the clear threat to productivity, it’s the leading proposal. But I’m here for your thoughts.” That cheery smile of his. “Stort?”

“We’re obviously still adjusting our picture of the ecosphere to incorporate these things,” I said. “Given the low species count on-world, having an apex predator that only emerges sporadically makes some sense. What happens if we remove it? We can’t know. If this was a matter of wanting to preserve a working natural ecosystem I’d say there would be too many potential imbalances generated by cropping the top of the food chain. But.”

“But,” the director agreed. Because we were not, after all, interested in preserving the ecosystem. Just that part of it that worked for us.

FenJuan’s eyes were boring into me; I didn’t meet them. “Historically,” I said, “in a managed agricultural paradigm, removal of the top predators has been accomplished very profitably. Wolves, sheep, so on. It’s not as though we’re going to have a problem with some Farmer population explosion. If some other species booms, we can manage the consequences. I say do it.”

“Director,” FenJuan put in, unasked. “I have yet to come to any understanding of the biology or relationships involved here. There’s a commonality between species I can’t account for. This world plainly went through some severe ecological crisis that left a depauperate web of interdependence. We don’t know—”

On our screens, the director settled back in his big chair. “We know all we need to. What this world could be worth to us. How much damage those beasts are capable of doing. An elevator cable! We’ll conduct a localized culling in your region first. Barring any obvious consequence, we can roll it out to the rest of the world and follow up with plant and personnel wherever these Farmer creatures are to be found.” His smile was genuinely pleased, a man who’s going to see a nice bonus. “Well done, all. I know it’s been tough, but you’re heroes.”

The local cull, when it first happened, was something to watch. Drone footage wheeling and spinning as our machines found and chased the fleas. Killed them as they leapt through the air, as they landed thunderously on the ground, as they emerged from their burrows. Wiping them out within 200 klicks of the processing plant.

And nothing broke. The Farmers kept on farming. The crops grew. The crops that, at a cellular level, seemed weirdly indistinguishable from the things that tended them. FenJuan was raising issues every day, by then. Desperate to communicate how weird their results were. Not doing their job, because their job was solely and specifically to identify aspects of the local biochemistry that could be profitably exploited. Instead of which, they were going nuts about how every critter just seemed to have this enormous bolus of unused genetic-equivalent information, with a huge overlap between species. And I think they’d just about worked it out, except by then they’d made such a nuisance of themselves that FenJuan was the very last person our bosses up in orbit wanted to hear from. Did this discovery open up new vistas of planetary exploitation for our already profitable operation? No? Then pipe down and stop using up comms resources.

The people the director did want to hear from were designing and deploying the hunter-killers. Our expanded drone fleet was greenlit: hundreds of machines shipped downwell and let loose across the globe. Wherever they found the fleas, they destroyed them. We felt we were liberators. Whole populations of Farmers could live without those monstrous shadows falling on them. Yes, we were making a species extinct, but it wasn’t a nice species. We were already on the next phase of occupation, a 10-year building plan where we’d fill the planet with farms and processing plants, replicating our first outpost over and over until there wasn’t an inch of the world that wasn’t working for us.

A couple of years into our agricultural expansion, the cacti disappeared. Not cacti, obviously. Species 43 in the Concern bestiary, but cactus enough that the name had stuck. We had a look one morning and there just wasn’t any more of it left. I suggested maybe it had been living off some sort of death-flea by-products, though the timing seemed unusually lethargic for that kind of interaction. I ended up working alongside FenJuan, and we found drone footage of the cacti stuff getting up and running around, so that Species 43 turned out to be the larval-or-something form of Species 22, and we had to recalibrate the records.

At around the same time, the little hairy critters that were Species 38 rooted down and grew long spires with puffballs on them, making them actually Species 17. Half a year later our existing Species 11s lost their poles and became another sort of thing we’d already seen, and so on and so on. To most of us it was a curiosity. To FenJuan it was a crawling horror that I was starting to share. All their snapping, bitching at me for not seeing, and I’d just written it all off as someone pissed their Concern work record was full of demerits. Except they’d been right and I’d been wrong.

There were no more cacti. That was what scared FenJuan. We watched a wave of transformations. Each form turned into something else, but none of it turned into the cactuslike Species 43. Then it was something else, where our current batch just metamorphosed and there were no new ones. None at all, anywhere on Chelicer. The dry country became less and less inhabited as species after species vanished away.

Or not species. That was what FenJuan had been trying to understand. Developmental stages. Not a circle of life, but a life cycle.

Our prized cheliceratos, which had been putting out runners and new tubers happily for over a decade, were suddenly ambulatory one morning, sprouting a thicket of spindly legs and just giving up their life of being agricultural produce. That got people’s attention. Around the same time one weird round critter rooted down where the Farmers were and became the new Chelicetato crop, and the dumbest of our colleagues reckoned that was all OK then. FenJuan and I had stopped trying to raise the alarm, by then, because it obviously wasn’t going to help. Soon after, some buried fungal-looking thing we’d found no use for sprouted legs and became new Farmers. And the old farmers … died off. Wore out, natural causes. Leaving only the least dregs we’d left of their crop. From which a handful of stunted things crawled, devouring their own left-behind husks and the last corpses of their tenders. They were tiny, but we recognized them even as they began to wearily dig down into the parched, lifeless soil. Nascent fleas, entering that dormant part of their cycle from which they would emerge, at some future date, into a world devoid of anything that could sustain them. Behind them, the whole ecosystem of life stages had been rolled up. There was nothing left of it. They were the last.

As we had harvested and plundered, we had been watching a decade-long series of transformations. One that had definitively ended. Life on Chelicer vanished. Plant forms, bug forms, just about every macrobiological creature dying off one at a time and not being replaced by a new generation. As though death had asked them to form an orderly queue.

There had been a mass extinction in Chelicer’s past, FenJuan and I reckoned. Something that had killed off everything except a hardy species that inherited an utterly impoverished planetary biome. Colder at the poles, warmer at the equator, but barren, desperate. So, over the ages, that species had developed to exploit every last opportunity that the world had left to it, not through speciation but through adaption of its life cycle. Gathering the meager resources of the world, concentrating them in living forms that could be harvested in turn. Sedentary stages, mobile stages, squeezing every possible niche of everything that could be gained and then transforming into the next phase of its long and complex chain of shapes. A desperate ecosystem of one, harvesting and gathering and recycling, each stage into the next, surviving everything thrown at it. Except us, who came and severed a single link utterly and irrevocably. Cut one thread and watched the whole unravel over a mere decade.

FenJuan and I were last off the planet, on the final elevator car along with the last salvage from our farming operations. It was on us, we had been told. We were the biologists, and we should have seen it coming. And they were right; we should. But all that would have done was salve our professional pride. I don’t believe for a moment they’d have listened to us if we’d said Stop. Stop isn’t the way of the Concerns. Stop doesn’t meet quotas or hit targets.

We stepped into the elevator car, FenJuan and I. We looked back over a world unrelieved by messy, complicated stuff, such as life. A failed commercial opportunity, as the report would say.

I wanted to say something. Possibly You were right. But what good would it do? We were both going to be back on ice when we reached the ship, with personnel files so dire they’ll probably never thaw us out again. But, like the life of Chelicer, we’re not important, compared to the bigger picture of the Concerns and their expansion. We humans go on, world to world, star to star, making the universe our own. But on Chelicer there will only ever be dust.