A: You read Bentham and Mill in college and thought, “Wow, I can orient my life around how to do the most good,” and for you this turned out to be designing a better website for people in California to get SNAP benefits. Why did you focus on these programs? And how did the website help?

D: The first thing we really did was to follow people through the process. We were helping actual people figure out if they’re eligible and deal with the phone interview, getting together documents for proof of all their income and expenses. We also developed a really close partnership with the San Francisco-Marin Food Bank, where they have assisters who help people do this all the time.

So, why these progams? The answer is that SNAP is the closest thing to a large-scale cash-like benefit we have. There are some smaller actual cash benefits like TANF

or Calworks,

but they’re much more restrictive programs. By our math, somewhere between 2 and 3 million people in California were eligible for an extra $100 to $150 a month on average. That’s a big delta. And then, how does a website help that? That’s a great question because a lot of people misunderstand about what websites can do — it’s not a magic equation. We tried to take each barrier in sequence and add interventions there.

A: Backing up — what are the barriers? Why were these uptake rates in California so low?

D: Honestly, I wish there was canonical research that could answer this. The rigor nerd in my head will say that participation rates like the one I quoted are a little bit tricky because they’re based on American Community Survey census data, and it’s not the same as the numerator in participation, which is administrative data. That is, we know how many people are enrolled, but the denominator — how many people are likely eligible — comes from ACS data. So we have to wonder, how great is this estimate? That said, there’s a much more interesting metric that we discovered in doing this work, which is procedural denials, and — I apologize, I’m going to get wonky for a second, but I’ve given this rant multiple times in the last decade, so I’ll give it to you.

A: That’s what we want.

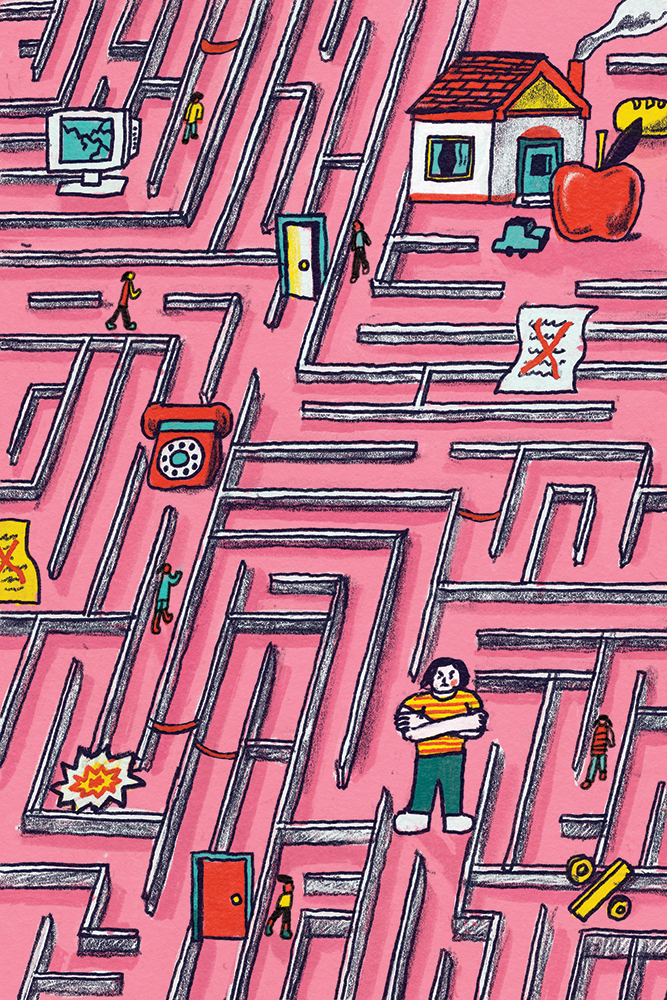

D: Okay, great. Procedural denials are when someone applies for benefits and they’re denied, not because they were ineligible or found ineligible, but rather because they couldn’t make it through certain parts of the enrollment process.

A: For example, they couldn’t get their documents together?

D: Yes — or, let me add nuance to that: if a document was requested of them that may or may not, strictly speaking, be required by the rules of the program. Another case: I was just helping someone on Reddit the other day who was saying, “my old employer just refuses to give me proof that I’m no longer employed there, and the agency won’t approve me without that.” That’s a good example of something that would be a procedural denial. It was not because they were ineligible. It’s because they couldn’t get that signed statement from their former employer.

Stepping back, I think of this as like a funnel. First you have a whole bucket of people who need the benefit. Then you have people who are aware that the food stamp or CalFresh or SNAP program exists. That’s actually meaningful because not everybody knows it’s a program, especially people who are middle income and suffer a sudden income shock. If they lose their job, they may not think, “Oh, food stamps are for me,” even though food stamps are based on monthly income.

There are also people in that bucket who attach a stigma to the program. They might think: “I, or a member of my family, do not have legal immigration status or am not a citizen; is this going to create a permanent record of me? Do I have to pay this back?” That’s all stuff in the stigma bucket before anyone ever applies.

So the first step is to make people aware of it and help them understand how the system works. Then there’s actually applying.

When we started working on GetCalFresh, the online application was about 200 questions across 50 or so screens. The truth is that most of those questions were not necessary. One reason for this is that in SNAP, at least, there’s a required interview anyway. And in fact, when you talk to caseworkers, sometimes they’ll say, “I wish I didn’t have all these incorrectly filled out income questions because people misunderstood what we were asking on the application.”

A: I’ve never interfaced with SNAP, but I have tried to help friends apply for Medi-Cal.

I’m a fairly smart verbal person who speaks English as a first language, and there were many parts of that online application process that I found baffling and I’m sure answered incorrectly.

D: Totally. Pamela Herd, an academic, alongside Don Moynihan, has done some great work on administrative burdens

— if I’m not mistaken, part of how she got really interested in this research area was she was helping a family member or friend apply for disability or something like that. And this person, a Ph.D. who studies public administration, was like, “I can’t get through this.” A lot of people are shocked by how difficult it is to navigate these programs. That’s why, coming back to the procedural denials, I think there’s effectively a lot of rationing of benefits by how tolerant of friction people are. That is the effect it has. And this can be captured in procedural denials, because if you have someone who said, “I need help, but I somehow didn’t get through the whole process,” that is a much better data point than a broad estimate of participation.

Now, just to finish up on the other barriers — it’s a complicated application. The questions can be confusing. It can be intimidating. There are lots of parts. My favorite question is, “Have you or any member of your household been found guilty of trading SNAP benefits for guns, ammunition, or explosives after. September 22, 1996?” That’s literally a question on the application. And it’s because there of a federal law that says the nine or however many people in the world who have been convicted of that are categorically ineligible for SNAP. I always think about the experience of people who are trying to ask for help. The application is asking, “Are you convicted of this? Are you convicted of that? Are you convicted of this other thing?” What is that saying to you, as a person, about what the system thinks of you?

There are two other two big barriers I want to mention because I think they’re particularly relevant right now. First is the required interview. Most of the time it’s a phone call. Often they’ll call from a blocked number. They’ll send you a notice of when your interview is scheduled for, but this notice will sometimes arrive after the actual date of the interview. Most state agencies are really slammed right now for a bunch of reasons, including Medicaid unwinding. And many of the people assisting on Medicaid are the same workers who process SNAP applications. If you missed your phone interview, you have to call to reschedule it. But in many states, you can’t get through, or you have to call over and over and over again. For a lot of people, if they don’t catch that first interview call, they’re screwed and they’re not going to be approved.

The last one we mentioned was documents. This is a big reason why people get denied. You have to submit all the pay stubs for the prior 30 days. If you only submit one pay stub and it doesn’t cover the whole period, you’re gonna get denied. If you don’t submit ID for all the household members, you’re going to get denied. Then there’s all these complicated edge cases: “I’m homeless. How do I prove residency in this county and state?”

So there are three big categories of barriers. The application barrier, the interview barrier, and the document barrier. And that’s what we spent most of our time iterating on and building a system that could slowly learn about those barriers and then intervene against them.

A: How did all this inform the design of GetCalFresh as it exists now?

D: One of the big things we did was start with the most minimalist application for benefits we could have, which is name, address, signature, date. This is federally compliant; legally it has to be accepted by the agency. There’s actually a federal rule about this called a right to file. The point of that rule, by the way, is so that if you need help, you can very quickly establish your first day of eligibility, and then once you finish up the process, all your benefits will go back to that first date.

Next, we brought that to the SNAP director here in San Francisco. He got someone from operations to come in and asked, “How many more questions would you really need to process this application?” And it wasn’t that many more. They wanted us to ask for phone numbers so they could call people for the interview. We didn’t have that on there. They wanted to know a bit about all the household members

Now, getting to your point about how a website can fix this — the end result was lowest-burden application form that actually gets a caseworker what they need to efficiently and effectively process it. We did a lot of iteration to figure out that sweet spot.

We also did a bunch of work to help people figure out what documents were actually needed for their situation and get them in easily and early, and create a way for them to submit those documents after the initial application, which varied county by county. In the early days, we literally faxed applications to some counties. I would ride my bike with some documents from Alameda County to the North Oakland office downtown because there was not an online way to submit them.

We also did a bunch of stuff around the interview, like giving people a heads-up by text message once they applied so that they knew they’d be getting a phone call. Then we texted people at regular intervals to ask if they’d had their interview yet — which was both a way to collect data and give them directions on the spot about how to reschedule their interview. As we scaled up we went county by county because that’s the way the benefits are administered in California. I mean, counties really are the ones who run the program here.

A: That’s quite unusual, right? To do benefits administration county by county.

D: I think 10 states do it that way. There’s a fun report, if you ever really want to nerd out, by the Center for Law and Social Policy called Ten Degrees of Decentralization. It’s about what different forms of county administration actually look like, and California is the most complex and most decentralized.

I’ll also note, it’s pretty important in terms of building a service like this that the contexts are so different. California’s largest county is Los Angeles, with 10 million people. The smallest is Alpine County, about 1,200 people. I’m pretty sure their human services director does all the SNAP. I met him once. His name’s not John, but I’ll call him John. The joke was that you’d see him at a meeting and ask, “John, who’s doing interviews right now?” Because it’s so small, it’s a very, very different context for service delivery.

It’s also a community where a lot of people know each other. It’s very rural. If you think of the far north, like Mendocino County, there are implications even for what online service delivery actually means, because for a lot of people, that’s their primary channel of contacting an agency or accessing benefits. Whereas in a really urban, dense county, like San Francisco or maybe Alameda County and parts of LA County, it’s a very different thing. Part of the California context of all this is that we’re really complicated, we’re really diverse, and we’re diverse across a lot of different dimensions, including what the optimal service design is. Even LA county — it’s so different to be up in the northeastern desert part of LA County, like Lancaster, versus in South LA. I also like the poetry of California’s baroque complexity and I love going around the state. The best part of working was getting to visit and try food in almost every county.

A: What’s the best food county? I’m going to guess LA, but I’m biased — that’s where I’m from.

D: That’s tough. I’ll kind of cheat. I really both loved working with San Diego County and loved eating in San Diego County. So I’m going to give it to San Diego County. But there’s plenty of counties with excellent food. You can’t beat any of the Southland counties — San Bernardino, Riverside, Orange, San Diego, and LA, all of those are great.

A: Okay, we’re getting distracted. California. Big complicated, baroque, system with all these county-by-county differences. I’ve looked at the GetCalFresh application. It’s very simple. So how do you handle the back end of that? Because this very simple 10-minute application then has to get to an office in Alpine and an office in Kern and an office in LA, and presumably they all need different things.

D: That’s actually one of the things that we had an underappreciated insight into. The approach we took to that is that, literally, when you came and filled out an application on our website, it would open up a web browser to the existing online application for that county and fill out the application as if it were a user taking the information you gave us.

We didn’t need to do some hard system integration that would potentially take years to develop — we were just using the system as it existed. Another big advantage was that we had to do a lot of built-in data validation because we could not submit anything that was going to fail the county application. We discovered some weird edge cases by doing this.

For example, we found that there were certain very small, weird zip codes that technically were absolutely in a certain county, but you could not submit in that county. And that led to bug reports, which led to that getting resolved. So that was how we sent it.

Then we worked with each county to figure out how they wanted to receive documents. Some wanted to receive them from the same online system. Some preferred their own document system — Fresno County had built a really excellent document upload system in-house. I always like the phrase “start where you are.” We started where there was minimal need for any institutional actor to change anything about their process.

I’ve also worked in government since then, both at the state and federal level. That was primarily on unemployment insurance. And I think it’s kind of an underrated pattern: A lot of times when you want to build a new front end for these programs, it becomes this multiyear, massive project where you’re replacing everything all at once. But if you think about it, there’s a lot of potential in just taking the interfaces you have today, building better ones on top of them, and then using those existing ones as the point of integration. It’s a pattern that I would like to see used more. I think it’s very promising.

A: This seems like the flip side of one thing that people complain about a lot with government technology, which is that so much of it is accretion — layers and layers and layers of things added on top of legacy systems, accumulating huge piles of tech debt. Are you saying that’s fine? Or do you think that there are ways to add these layers to existing systems without compounding that problem?

D: It’s a good question. I’m a firm believer that much knowledge of systems is gained from acting in them, rather than trying to study them. We had better data on why people were denied benefits than perhaps anyone in the world — but it came from running a benefits application service at scale. I don’t know that you could have studied the problem to death to get to that understanding. And so I think that “start where you are and integrate with what’s there today” is a reflection of the notion that an attempt to separate understanding from acting will lead to false models of the system.

Government tends to take a more high-modernist approach to the software it builds, which is like “we’re going to plan and know up front how everything is, and that way we’re never going to have to make changes.” In terms of accreting layers — yes, you can get to that point. But I think a lot of the arguments I hear that call for a fundamental transformation suffer from the same high-modernist thinking that is the source of much of the status quo.

If you slowly do this kind of stuff, you can build resilient and durable interventions in the system without knocking it over wholesale. For example, I mentioned procedural denials. It would be adding regulations, it would be making technology systems changes, blah, blah, blah, to have every state report why people are denied, at what rate, across every state up to the federal government. It would take years to do that, but that would be a really, really powerful change in terms of guiding feedback loops that the program has.

A: And I think feedback loops are a really important concept here — right now, what is the feedback loop if the benefit system isn’t working?

D: Exactly right. Unless they violated a federal regulation that can be pointed to, what do you do? One of the things I think would be very powerful in terms of feedback loops is if we could operationalize the problem of people not being able to get through the system into metrics that are legible to government.

With SNAP, we already look at payment accuracy, which measures whether people who successfully applied for benefits are being paid the correct amount. If we had a corollary measure of how long it took people to fill out an application, or how many people didn’t successfully complete it, or how many people applied but were denied for eligibility for procedural reasons, it would be offsetting feedback loops that allow states to say, “We have an extremely low payment error rate” while there are tens of thousands of people not getting through the process who are likely eligible.

A: This relates to another thing I’ve been thinking about, which is that when you start to read about civic technology, it very, very quickly becomes clear that things that look like they are tech problems are actually about institutional culture, or about policy, or about regulatory requirements.

I’m curious why these issues so often come up in the context of tech, or are interesting to people whose background is in tech or who are drawn to technical solutions for them.

D: In Political Economy of Industrial Societies, we read all the classical theories of political economy. And we also read Hegel. So let me give you the thesis, the antithesis, and the synthesis.

There’s this starting point thesis: Tech can solve these government problems, right? There’s healthcare.gov and the call to bring techies into government, blah, blah, blah.

Then there’s the antithesis, where all these people say, well, no, it’s institutional problems. It’s legal problems. It’s political problems. I think either is sort of an extreme distortion of reality. I see a lot of more oblique levers that technology can pull in this area. For example, I mentioned measuring how many people succeeded at getting benefits. If you just had a paper application for benefits, you would never be able to actually measure how many people started versus how many people finished. Technology makes that pretty trivially measurable. It’s not a totalizing resolution of all problems, but it’s an incredible difference from paper, where we have no ability to measure this at all.

You could think about a lot of other things. If you have an application where you think people are struggling, you can measure how much time people take on each page. A lot of what technology provides is more rigorous measurement of the burdens themselves. A lot of these technologies have been developed in commercial software because there’s such a massive incentive to get people who start a transaction to finish it. But we can transplant a lot of those into government services and have orders of magnitude better situational awareness.

I think it’s also that people jump on this because the technology world is so, so, so fast and government is so, so slow that the absolute difference starts to become extremely glaring. There’s an argument which I buy, which is that people’s expectations change as their commercial experiences change, so they start to expect something different from the government.

A: Do you see LLMs as part of this? I remember thinking even a couple of years ago that explaining benefits application seemed like a really great use case.

D: Yeah, I have a lot of optimism about this. LLMs seem to be a fundamental breakthrough in manipulating words, and at the end of the day, a lot of government is words. I’ve been doing some active experimentation with this because I find it very promising. One common question people have is, “Who’s in my household for the purposes of SNAP?” That’s actually really complicated when you think about people who are living in poverty — they might be staying with a neighbor some of the time, or have roommates but don’t share food, or had to move back home because they lost their job.

I’ve been taking verbatim posts from Reddit that are related to the household question and inputting them into LLMs with some custom prompts that I’ve been iterating on, as well as with the full verbatim federal regulations about household definition. And these models do seem pretty capable at doing some base-level reasoning over complex, convoluted policy words in a way that I think could be really promising.

Also, right now, caseworkers are spending a lot of their time figuring out, wait, what rule in this 200-page policy manual is actually relevant in this specific circumstance? I think LLMS are going to be really impactful there.

A: I also wanted to talk about something that came up when we were emailing, which is a unique feature of California’s benefits policy landscape. I think you charmingly referred to us as the “eat worms” state, meaning that we like to take on really ambitious benefits policy goals. So, why are we like this? What implications does that have?

D: That quote came from very early in my career when I was working for an entity that did analysis of very specific health insurance rules. And someone I met jokingly said 15 years ago, “Yeah, California is the ‘eat worms’ state. Any time the feds have some new innovative waiver, new program, new option, California’s like, ‘Yes, yes. We eat worms! You want us to eat worms? We’ll eat worms.’” He didn’t mean it as a knock. California seemed to really try to take every ambitious option that the feds give us on a whole lot of fronts.

I think the corollary of that is that we don’t necessarily get the fundamental operational execution of these programs to a strong place, and we then go and start adding tons and tons of additional complexity on top of them. So, for example, during the unemployment insurance crisis in 2020 and 2021, there was proposed legislation that would require online services to be available in, I want to say, 20 languages. And on the one hand, we are a diverse state. We have a lot of people who don’t speak English as their first language. But also there were tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of claims backlogged, not being paid at all. And this was legislation saying, now add 18 more languages. There’s a political economy problem here — a crisis is when you have the attention to get things done. But, you know, the fundamentals of the UI system were not working at all. And I think a lot of California has that.

There’s a bit of a political aspect here. The California legislature is now supermajority Democratic. It is certainly the case that I’ve seen some productive tensions in counties where there’s more of a mix of that and what you might consider California-style Republicans who are like, “We want to run this like a business, we want to be efficient.” That tension between efficiency and big, ambitious policies can be a healthy, productive one. I don’t know to what extent that exists at the state level, and I think there’s hints of more of an interest in focusing on state-level government working better and getting those fundamentals right, and then doing the more ambitious things on a more steady foundation.

A: It seems really hard to build up personnel capacity to do that when it’s distributed over all the different counties.

D: Yeah. There’s also the problem that it’s never going to pay to be an eligibility worker. Parts of California are extremely expensive to live in. How do you expect to attract and retain a long term workforce in a place like San Francisco, where the cost of living just keeps on going up? A lot of states are struggling with this, not just California. But it creates a particular problem in these really high-cost-of-living parts of California, unless you somehow adjust the public sector wages accordingly, which is hard to do for some structural reasons like Prop 13.

Still, we’re a big enough state that there’s probably a mix of benefits and downsides to counties running the programs. There is an interesting side effect, though, which is that I’m not sure many people realize if they’re having a problem with these programs that their go-to is not a state legislator or the governor — it’s their county supervisor’s office.

A: County supervisor, the most important neglected position. A lot of things that really impact people’s lives are the county supervisor’s job — parole, for example, is managed at the county level in California.

D: This is an interesting, unique aspect of California, which is that counties have this outsize importance as an element of government. County supervisors in LA are called the Five Kings or the Five Queens, because each of them represents 2 million people. There’s a former secretary of labor who’s a supervisor, because that was what came after being secretary of labor. I’ve actually heard, interestingly, that part of the dynamic between the state and counties is that sometimes state legislators want to go home and become county supervisors. And the counties have a strong voice in the state in these programs. They have a very strong voice.

A: I’m curious if you have any thoughts about things California could do to build up that implementation capacity.

D: I think there’s a few things. One is if you talk to any wonky person in the state, Prop 13 comes up as a relevant structural constraint.

A: Can you explain Prop 13?

D: Prop 13 caps property taxes at a certain rate, so you have people who bought a house in 1980 paying 1980 taxes plus a maximum of 2% a year, whereas property values, as it turns out, have gone up much more significantly in the state of California since then. This has led the state to be much more procyclical in its fiscal condition — meaning, it relies much more on income and capital gains revenue instead of property taxes. That’s why you see a bit of a feast and famine, where when there are good years, a bunch of program expansions, and then when there are bad years, a bunch of cuts to programs — because it’s much more tied to things like cap gains. It swings much more than in other states where the property taxes are a greater share of the overall tax revenue, because property taxes are much more stable.

I don’t have any silver bullets here, but I think that we should be routinely evaluating public services for how many people start and how many finish. There are also pay scales for civil servants and for state government. I believe CalFresh, the state’s SNAP program, is the biggest food assistance benefit in the world, and the person who oversees that program does not make that much. I think the other structural thing that’s interesting is that a lot of state government and state public policy really are very Sacramento-centric. I think we need a different talent pool to pull from, because Sacramento is just not representative of the state of California, period. Setting aside even the smaller, less populated parts of the state, LA and the Bay Area are the overwhelming experience by population of what it means to be in California. The capital is not the primary city. I think you see in general some interesting side effects from that.