The solution seems so obvious. A region synonymous with abundant sun is hungry for more electricity. Given Africa’s colossal untapped solar radiation, the continent should be installing solar panels at a furious pace. But it’s not. Though home to 60% of the world’s best solar resources, Africa today represents just 1% of installed solar photovoltaic capacity. 1 The entire region of 1.2 billion people has just one-fifth the solar capacity of cloudy, temperate Germany.

The World Bank designed the Scaling Solar program to set Africa on a course to sustainable energy. Instead, it shed light on how a lack of transparency in the climate and development industry hampers progress.

One sad tale begins with a high-profile initiative that explains a lot about Africa’s missing solar boom. In 2015, the private sector arm of the World Bank launched Scaling Solar to prove that bundling support for investments could blaze a trail to a solar future for everyone. Its first big project was impressive: Zambia, one of the world’s poorest countries, was able not only to attract private capital but also to slash costs for power by more than 80%. Scaling Solar’s next project in Senegal came in even cheaper. Then a 2019 solar farm in Uzbekistan was even lower. And then … nothing.

Scaling Solar did not scale. By the narrowest of measures, the initiative’s own project pipeline dried up. 2 Zambia, the initiative’s shining example, appears to have abandoned the program by reverting to backroom solar deals. 3 And judged by its grander mission — a demonstration of how a massive solar rollout could be done efficiently — Scaling Solar has been an even bigger disappointment. In 2022, all of Africa added less new solar capacity than Belgium. That year, at least 30 countries on the continent added no new utility-scale solar capacity at all.

Of course, plenty of reasons explain why an African solar boom has not yet materialized. An array of actors — governments, developers, investors, even environmental activists — have all played a role. And it’s not that the World Bank holds primary responsibility for building solar farms in Africa; it’s that the Bank is the sole global institution that wears all the hats of planner, advisor, and financier for infrastructure, while its mission is to fight poverty and climate change. If any single organization should be ideally placed to catalyze Africa’s solar markets, it’s the World Bank. The organization proudly accepted that mantle to showcase to the world how it could be done. Only it didn’t.

Let’s not leave one billion people behind

The mistakes of Scaling Solar are helpful for thinking about not just the barriers to deploying solar power in high-risk markets but also the future of our collective battles against poverty and climate change.

Some 760 million live today without any electricity, while at least three billion people live without reliable power. Most people in Africa today use less electricity than a typical American family refrigerator. So while the rich world is racing ahead to electrify everything and build out a highly digital economy, billions of people are being left out. Energy poverty is all a colossal waste of time and money, and it deepens poverty by depressing living standards even further. Imagine the disruption to your life if the power went out at your home several times per week — or disappeared altogether. This reality is devastating to everyday life.

The harms of energy poverty are even worse when multiplied across an entire country. Modern commerce, most industries, and the entire digital economy all depend on 24/7 electricity. Any economy where outages are regular (or where costs are very high) is going to be, by definition, inefficient and unable to compete globally. Most African manufacturing firms cite electricity as one of the top constraints to productivity growth. Multiple studies have shown that power outages in Africa are job killers. 4

So while lack of household power makes people’s lives worse, energy poverty outside the home destroys economic opportunity. Every year some 12 million young Africans leave school, and yet only a tiny percentage find well-paid jobs — and most can’t find work at all. Employment in Africa, like pretty much everywhere else, is a first-tier political priority. And no economy can create lots of jobs without abundant reliable power. 5

Show me the money

Global investment in solar is impressive. The International Energy Agency reports that worldwide clean energy investment rose to $1.7 trillion in 2023, a more than 50% jump from five years earlier. 6

Underneath the headline numbers, however, the trends are far more worrying. Nearly all of the capital is flowing to rich nations or the three big emerging markets of China, India, and Brazil. In 2022, China alone installed 100 GW 7 of new solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity, nearly ten times as much as the 11 GW of operating solar capacity in the whole of Africa.

It’s even worse closer up. Of the continent’s total installed solar capacity, just three relatively wealthy countries — South Africa, Egypt, and Morocco — account for about 70%. The important regional bellwethers like Kenya, Ghana, or Senegal have very modest solar capacity, while the large markets like Nigeria, Congo, or Ethiopia have next to none.

The World Bank and how infrastructure gets financed

There are many reasons for the shortage of solar investment in sunny Africa. Costs are always higher in riskier markets, and consumers are less able to pay for power. The national utilities expected to sign long-term solar contracts are mostly bankrupt because politicians don’t like to pass the full costs of producing electricity onto consumers. African governments that typically backstop solar farms with public guarantees are under mounting debt distress, so they’re less able to calm the fears of investors. And, of course, the effects of the pandemic drove interest rates higher and squeezed supply chains, all of which derailed potential projects. 8 If built today, the same solar farm will cost twice as much in Ghana as it does in the United States due to interest rates alone.

Yet these barriers are precisely what development finance agencies are built to overcome. They are designed to work with investors, companies, and governments to mitigate risks and drive down the costs of projects that would deliver impact but can’t yet take off organically. A suite of tools — below-market loans, risk insurance, and guarantees — can help to catalyze projects in places where the private sector is too scared to go. Solving the missing solar boom in Africa is a challenge tailor-made for them. And none more so than the World Bank.

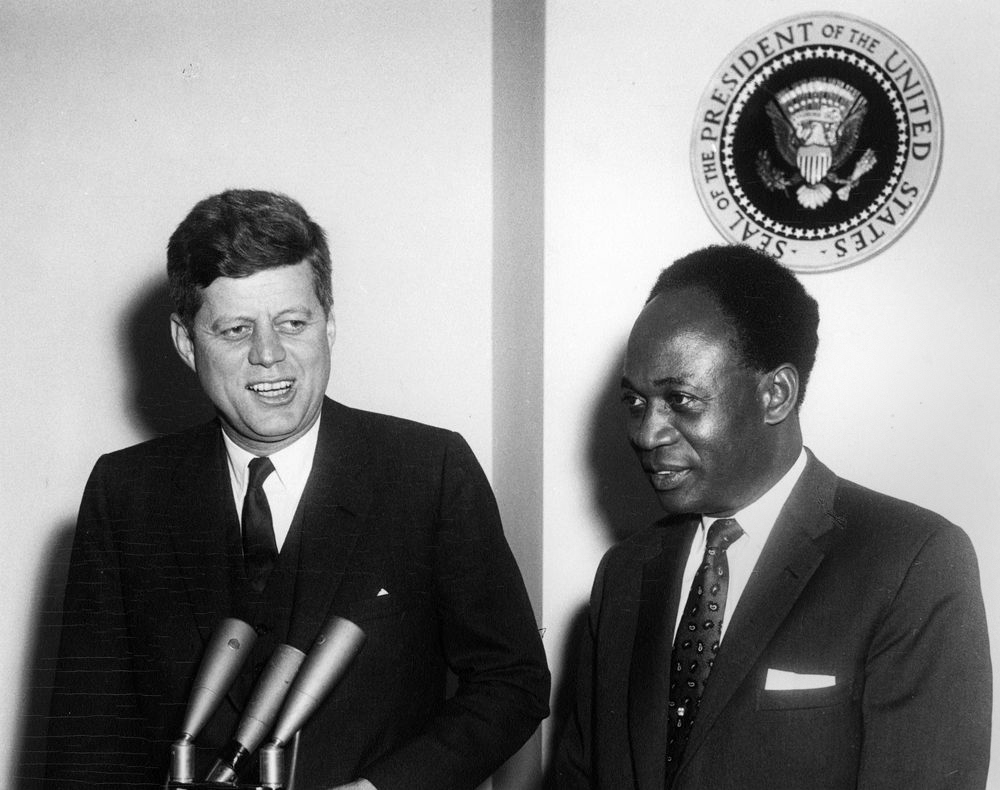

The World Bank has been involved with energy investment from the very start. The agency’s loan for a hydroelectric dam over the Volta River in Ghana was critical to President John F. Kennedy’s strategy to counter Soviet influence. Fast forwarding half a century, President Barack Obama launched Power Africa in 2013, a U.S. government initiative to push investment for electricity across the continent. The effort uses a mix of grants, loans, and technical help to make private investment in power projects feasible and attractive. A founding partner was the World Bank, led by Jim Kim, who was, not coincidentally, appointed to the job by Obama. 9 So it was logical that the World Bank would play a big role again in mobilizing capital for African electricity projects.

Scaling Solar was supposed to show the way to a clean energy future

In 2015, the International Finance Corporation, the World Bank’s private sector arm, rolled out Scaling Solar, a high-profile initiative funded in part by a $5 million grant from the U.S.-government-led Power Africa. Expectations were huge. The IFC’s rollout claimed that “large-scale photovoltaic solar power can be quickly and economically developed.” 10

Global prices for solar panels kept dropping, yet many countries short of electricity weren’t attracting investment to build solar farms. The IFC’s idea was fairly simple: Make it easy, cheap, and quick for governments and solar developers to build by bundling all the needed steps and financing together. Scaling Solar’s “one stop shop” would show politicians and investors how large-scale solar farms could be done profitably. Once the path was illuminated, the investment would naturally flow. Africa would soon be blanketed in solar panels.

Jim Kim touted Scaling Solar widely, especially after the launch of the first pilot in the southern African nation of Zambia. In a 2017 TED Talk, he bemoaned the trillions of dollars sitting idly in low-interest instruments while poor countries could make better use of that capital. “Can you bring private sector players into a country and really make things work?” Kim asked. “Zambia went from the cost of electricity at 25 cents a kilowatt hour, and by just doing simple things … we were able to bring the cost down” to 4.7 cents.

Solar below 5 U.S. cents was a stunning accomplishment in a country where interest rates were very high and political risk was a major investor deterrent. A prime selling point for Kim was that cheap solar could be had for everyone without subsidies. In meetings with leaders across Africa, he repeatedly made a compelling case that they, too, could get low-cost solar by just following the IFC’s “simple” steps. World Bank officials also explained clearly that “there aren’t any implicit or explicit subsidies involved in the deal … [We] simply helped structure the auction based on the best global practices.”

The “no subsidies” spin was no accident. Subsidies, or special payments to reduce the cost, had become taboo in development policy circles because they can create reliance and distort market prices. A need for subsidies runs counter to the notion that the private sector can deliver solar power on commercial terms and at scale. Of course, rural electrification in the United States, and virtually every other successful national electrification program, has relied heavily on some form of subsidies. 11 Yet in Africa, the hope was that electrification could be done differently. All the World Bank had to do was package everything together — “just do simple things,” in Jim Kim’s words — and energy would flow from the sun to the people who needed it.

Scaling Solar wasn’t so simple

A deep dive into Scaling Solar by analyst Teal Emery is revealing. 12 After digging into public documents and interviewing many of the key players, Emery concluded that Scaling Solar was a thoughtful and well-designed program. It packaged the whole value chain of getting a solar farm from an idea to a shovel in the ground, with help preparing the project, designing the bidding, and managing the legal documents.

Yet a defining feature that explains the rock-bottom prices is this extra help at virtually every stage. While some efficiencies can certainly be gleaned from streamlining and bundling, an 80% decline in the cost of power requires cheaper upfront capital, free technical and legal help, and loads of other special goodies to drive down the final price. A simple fact likely explains why Scaling Solar never scaled: The program was loaded with the one thing no one wanted to admit to — subsidies.

Despite the claims of being subsidy-free, the IFC was open about financing and project support. But in the early stages, their magnitude was not made clear. Although the interest rate and tenor of loans provided have not been disclosed, reasonable assumptions suggest that the cheap debt financing of the project amounted to roughly a $10 million yearly subsidy. Others — extensive project preparation carried out by the IFC, the halo effect of investments from the World Bank, and the land costs for the project — were implicit. In total, Emery estimates that every $1 of financing from the various development actors catalyzed only 28 cents of private sector financing. As he notes, “Private investment was additive, but it was not multiplicative.”

Subsidies can be hidden, denied, or relabeled. But, in the end, they always have to be paid by someone. And if the next project doesn’t have them, the math no longer works. If the whole premise of Scaling Solar is based on special payments that are hidden, there’s little chance it can deliver on its objectives of making solar cheap, easy, and market-driven.

Shining a light on solar power costs

Multiple lessons can be drawn from the mistakes of Scaling Solar. These lessons are not Monday-morning quarterbacking about design flaws or unforeseen gaps in the analysis. The specific details of the program appear to have been sound, built on creating a sequence of steps to tackle very specific obstacles to getting solar farms financed and built. Instead, the mistakes are concentrated in the lack of transparency and especially in the irresponsible mis-selling of the program. In other words, the failure of Scaling Solar rests not with the project team, but with the World Bank’s senior leadership.

The biggest takeaway is about openness. Transparency is a core principle of sound development policy and, supposedly, of World Bank operations. Yet in hindsight it is clear that Scaling Solar was not transparent enough — and was in some cases explicitly misleading — about aspects of the program, especially how free assistance or subsidized capital was used. In fact, most of what we know about the initiative is because of the transparency of one of its funders — the U.S. government 13 — rather than because the Bank was open. The impact of such opacity has been substantial. By hiding or denying the various ways it nudged Zambia’s solar farm along, the Bank failed not just to provide a recipe that could be replicated, but to even reveal the key ingredients.

Think of it this way: What if I told you, “You, too, can get rich by following a few simple steps I used to build my successful business!” but I failed to share that I started with a gift from my rich uncle? You’d rightly accuse me of selling snake oil. The World Bank sold Scaling Solar in a similar way: super cheap solar, easy to follow steps. Yet without being open about the free or below-market help for project preparation, legal support, land acquisition, financing cost, and more, the sales pitch was misleading.

The secrecy mistake goes beyond sharing details of the individual solar projects. The whole notion of Scaling Solar was to scale. That means the initiative was supposed to demonstrate how it could be done so that others could copy, allowing the invisible hand of the market to do its magic. Private capital, once shown the way, would then deliver cheap, reliable power for poor countries. But markets function best when prices and terms are widely known. Competition can drive down costs and reap efficiencies, but only with price disclosure. To get a fair deal, buyers need to know prices and be sure they are comparing apples to apples. (If you went to buy a refrigerator and the salesperson refused to tell you what your neighbors paid, you would assume you were getting a bad deal — and you’d be right.) By hiding the true terms of the pilots, Scaling Solar did not create an environment of open market competition, but did rather the opposite.

Both sides of the table

A second lesson: The inherent conflict of interest faced by the World Bank has created perverse incentives to prioritize its own transactions rather than the long-term growth of the markets it’s supposed to serve. The IFC and other organizations like it are tasked with fostering private markets where they don’t yet exist. But these agencies are also investors. The IFC attempted to show how to build an open competitive market for utility-scale solar in Zambia while simultaneously demonstrating the success of the first pilot project. Pressures to make that one project a triumph — something Jim Kim could promote to foreign leaders — were huge. But in trying to do both, it succeeded in neither.

The IFC is not unique. All development finance agencies are seeking both to solve the collective action problem of imperfect markets and to ensure profitability for their own investments. The internal incentives for the latter are very strong. The profitability drive often undermines the broader objectives. Again, this points the finger not at the dedicated Scaling Solar team but at bank leadership.

Such pressures could have been mitigated with a policy decision to enforce transparency and high standards. Greater openness of Scaling Solar, including a full accounting of the subsidies along the way — and even publishing the contracts themselves — would have been far more productive. The true final price may very well have been a lot higher than 4.7 cents. Or the Bank could have made the case about why, if the donors want more cheap solar in Africa, they need to provide more subsidies. That would have illuminated a plausible path forward, rather than creating a demonstration project that no one could possibly repeat.

The very real damage from misleading public relations

Overselling was also a mistake. On the one hand, it’s understandable that Jim Kim wanted to declare victory. He was under constant pressure to raise additional funds from shareholders and show results. Premature celebration of one promising pilot project could perhaps be forgiven. But the way that Scaling Solar was oversold actually wound up damaging solar markets in other countries. If Kim’s pitch was correct and everyone could get 5 cent solar for just doing simple things, who would ever pay more?

Nigeria was one obvious victim. 14 Around the same time that Scaling Solar was getting off the ground, Nigeria’s planners were hoping to add solar to an energy mix heavily dominated by gas plants and diesel generators. In 2016, contracts were signed with 14 different private solar developers that would have brought $2.5 billion in new investment and added over 1,000 megawatts of clean power to the grid. The agreed price was 11.5 US cents per kilowatt-hour — high by global standards but the outcome of a largely competitive process and arguably justified given market conditions. Most of all, it was the very first step for Nigeria — a massive economy with more than 200 million people that was generating less than 1% of its grid electricity from solar. But then, citing the lower prices reported from Zambia, the government of Nigeria balked. The solar farms stalled. Some of the contracts were later renegotiated, but, nearly eight years later, none of the 14 have been built. Solar still accounts for less than 1% of Nigeria’s grid capacity.

Learning from failure

A final lesson is about humility. Scaling Solar was an exciting experiment that could have paved the way to open competitive solar markets across a continent desperate for electricity. The initiative has neither created a pathway for more projects nor lived up to its grand original vision of creating a viable solar marketplace. Yet the World Bank has stubbornly shown little self-reflection.

Emery shared his analysis with IFC leadership. He received no reply. After the study was publicly released, the IFC effectively issued a denial, claiming they were fully transparent and that the program is a success. 15 Despite multiple opportunities to engage with Emery or other constructive critics, the World Bank — a public agency funded by public money to fight global poverty — has stonewalled. The opportunity to promote transparent contracting and clarity on subsidies, and to make an open honest case for how to get solar deals done in the world’s riskiest markets, was sadly lost.

Bigger than the Bank

The World Bank’s missteps go beyond that one (admittedly important) institution. Misguided public relations and inherent conflicts of interest exist across several dozen semi-public agencies that few people have ever heard of, like the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation or British International Investment. But these agencies are at the very epicenter of the world’s climate strategy. Global promises to catalyze trillions of dollars of private investment for clean energy around the world rely on these organizations.

For those in government, business, or philanthropy hoping to create a solar future in Africa, the lessons of Scaling Solar apply to their plans too. Transparency over secrecy. Awareness of conflicts of interest. Substance over salesmanship. And an honest recognition that delivering cheap power to poor people has always required subsidies. Maybe even lean into it. Why not just abandon the idea that private investors will solve global energy poverty and make the case why everyone needs power, dammit? Let’s use climate finance to drive down the price of solar power for the poor. That’s how we deliver on global development goals. That’s how we break the climate deadlock.

A fresh start is possible. The World Bank has a new president, Ajay Banga, who started in June 2023 and pledged to focus on, ahem, private capital to tackle climate change. He has a new opportunity to push the institution to be more transparent. Banga can help to spur solar investment by establishing norms for open electricity markets. And he can start by being blunt with donors about needed subsidies and forceful with governments about the benefits of transparency.

Meanwhile, Zambia, the poster child for Scaling Solar, can also restart its solar plans anew. Unpaid electricity bills from undisclosed contracts helped create a mountain of debt, which then prevented the government from signing new contracts. Fortunately, Zambia has just concluded a debt-relief deal with its official creditors, which should allow it to once again sign renewable energy contracts. But Zambian officials can succeed in rolling out a solar future only if they, like their funders, are open about what they’re really signing.

- World Energy Outlook (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2022). ↩

- Although its website says four potential projects are still active, all the updates are now at least two years old, which is more time than the program says it takes from start to finish. ↩

- The next solar farm agreement the country’s public utility signed was with a firm whose headquarters appear to be a UPS store in a suburban Atlanta strip mall. ↩

- Justice Mensah, “Jobs! Electricity shortages and unemployment in Africa,” World Bank, 2018. ↩

- Offgrid solutions are helpful for some household energy services (e.g., lighting, fans), but they cannot yet provide sufficient power for energy-intensive appliances, like air conditioners, or deliver at a scale for commercial and industrial uses. Solar minigrids are a promising midsized solution for rural enterprises, but, so far, they’re much more expensive than grid power and have yet to prove commercial viability. Maybe they will one day, but not yet. ↩

- World Energy Investments (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2023). ↩

- One GW can power about 900,000 American homes. ↩

- Ben Attia, Katie Auth, and Todd Moss, “New Headwinds to Clean Energy” Energy for Growth Hub, August 2022. ↩

- The World Bank president is notionally elected by the members, but in practice the White House always picks the leader in an implicit deal with Europe, which always selects the head of the sister International Monetary Fund. ↩

- “World Bank Group Launches “Scaling Solar” to Create Market for Solar Power in Africa,” IFC, January 29, 2015. ↩

- e.g., the Rural Electrification Act of 1936. Even today the USDA subsidizes rural electricity, while the Department of Energy just announced billions in new public guarantees for transmission lines. ↩

- “Solar Can’t Scale in the Dark: Why lessons about subsidies and transparency from IFC’s Scaling Solar Zambia can reignite progress toward deploying clean energy,” Energy for Growth Hub, May 2023. (Full disclosure: My nonprofit organization commissioned Emery’s analysis.) ↩

- A U.S. government review found that pricing was not transparent and “the key stated rationale of the Scaling Solar model — that it would unlock private sector financing — has not eventuated in practice.” See Review Study of the Zambia Scaling Solar Program, (Washington, D.C.: USAID, 2018). ↩

- Precious Akanonu, “How to Resolve the Tariff Disputes Blocking Nigeria’s Solar Project Pipeline?,” Energy for Growth Hub, February 2019. ↩

- “IFC Responds to Story About Its Scaling Solar Program in Africa,” Bloomberg, May 22, 2023. ↩